I first heard about the tunnel when I was in second year. Nabeel, a friend of mine whose knowledge of the campus I hold in high regard, told me there was an underground passage that leads from the William G. Davis Building to the North Building. On snowy and rainy days, students would pack tightly into the tunnel and travel from one end of campus to the other without coming into contact with a single drop of precipitation. As rumour has it, the university closed off the tunnel without reason a few decades ago.

My mom attended UTM back in the day when Davis and North were the only buildings that separated the deer from the woods, so I asked her about the tunnel.

“An underground tunnel? That sounds dangerous,” my mom scowled. “I don’t know about a tunnel, but I wouldn’t have risked it—and neither should you.”

Of course, my mother’s disapproval only served to spur my curiosity. I set out in search of the tunnel.

A few nights later, I pitched the idea to Nabeel. We were studying late at night in the library and decided that adventure was more important than midterms. Discovery of the passage would make us campus heroes and would help my friend “bag a lot of chicks”. (His words, not mine.)

We left our bags and jackets in the library, as is customary if you don’t want to lose your table. Turning up the brightness on our phones in preparation to enter the dark space, we headed to Davis. I applied some of my hard-earned university logic and figured that the tunnel entrance would be in the basement.

The Davis dungeon is scary enough during the day when one or two science TAs are down there doing research, let alone at midnight. We crept warily down the hall, jumping at the sound of our own footsteps echoing off the red brick walls.

After desperately trying dozens of doorknobs, we rounded a corner at the farthest end of the basement. We were about to give up when I saw the light—literally. Bright fluorescent bulbs shone through a gap between the wall and the ceiling. The space was about 12 inches high and three metres wide—just enough space to climb up and crawl through. We had found the tunnel; we were so sure of it.

Nabeel clasped his hands together and hoisted me up toward the gap. Several grunts and bruised knees later (get your mind out of the gutter!), I grasped the top of the wall and craned my neck to peer into the tunnel.

Except it wasn’t a tunnel. I still don’t know what it was. There were some pipes and large metal objects that made clanging noises, but it certainly wasn’t what we were looking for.

Disheartened and in need of caffeine, we retreated back to the library and abandoned our mission.

Two years later, I found the tunnel.

The university agreed to give Medium Magazine a tour of the underground path after I swore an oath of secrecy regarding the location of the entrances. Contrary to rumour, the tunnel doesn’t make a safe passage.

The day of the interview, I imagine myself as the sidekick of Indiana Jones, braving treacherous territory like all the great explorers before me. Rick Peters and Christine Tan from Facilities Management and Planning lead our photo editor, Edward, and me into the Central Utility Plant—that odd grey building next to the Instructional Centre. A narrow brown metal staircase spirals down to a cavernous basement decorated with winding pipes. Rick pushes open a red door and warm, dry air washes over me. I lick my lips, suddenly parched.

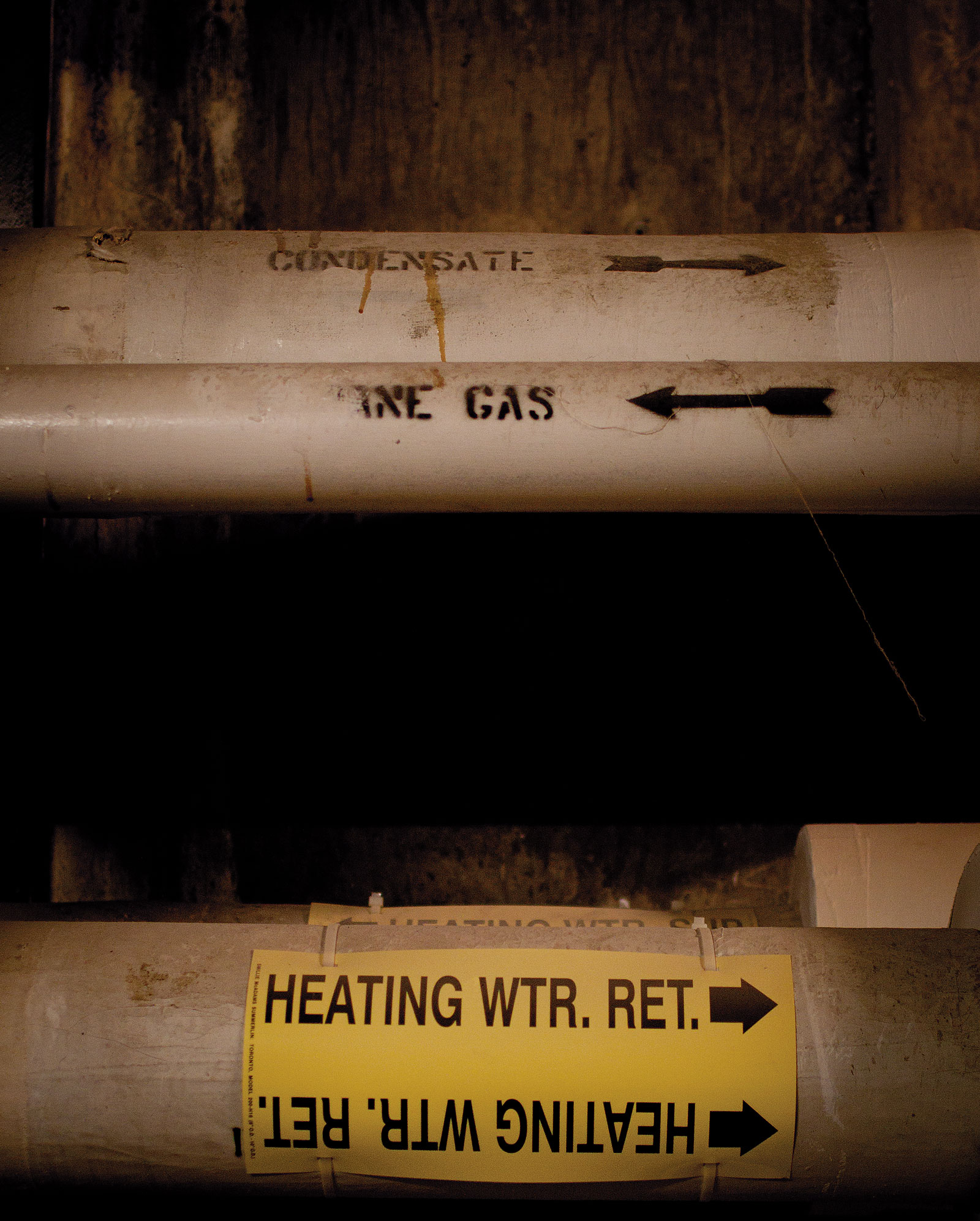

A row of fluorescent lights shine on gigantic white pipes that snake down the winding tunnel. The door clicks shut, encasing us in a 1,500 foot long cement tube. I fight the urge not to turn the bright red wheels attached to the pipes overhead as Rick begins to explain the purpose of the tunnel.

“This is not a place for students. Someone could get hurt or damage the infrastructure,” Rick cautions. “This tunnel provides energy to most of the buildings on campus.”

The service tunnel was built in 1968 to accommodate the district heating and cooling system that now pumps energy to the Davis Building, the Health Sciences Complex, the Hazel McCallion Academic Learning Centre, and a portion of the Student Centre. The pipes run steam and cold water across campus. The district system—a centrally located energy supply—saves space in the academic buildings and allows for better monitoring and maintenance of the campus’ energy supply.

Moving slowly through the tunnel, Rick locates our position on campus. Every few minutes, we creep along under a different parking lot or next to another building. The white pipes pierce the grey cement walls and slither toward the Health Sciences Complex (to power medical labs), the library (to lend power to the mobile stacks), and Davis (to turn on the iced capp machine at Tim Hortons).

The tunnel under Davis is more spacious; it also serves as storage. Fume hoods and cabinets with red warning labels that read “ACID” and “FLAMMABLE” litter the floor along the wall opposite the pipes. A long cage holds hundreds of desks and chairs—desks and chairs that the custodial staff will haul up to the gym in April for exams.

Two brown doors mark the end of the path. On the opposite side, students buzz through the halls on their way to a lecture or the gym. Rick places his hand on the doorknob.

“Remember, the tunnel is not open to the public,” Rick says. “The location shouldn’t be published.” The door swings toward us.

Edward and I blink in the bright light of the hallway. A student speeds by without noticing us. The tunnel was right there the whole time, completely accessible, breathing life through the campus so students can work out at the gym and watch YouTube videos in the library.