“It was a simpler time. Mississauga as you know it is not how it was then.

“Most of Mississauga in those days was apple orchards. The North Building was the original campus. When I got there, the South Building was less than two years old. None of the ancillary things that you now take for granted—all of the additional housing, all of the additional buildings—none of those existed then. There was no Square One—the largest mall we had in the area was Sheridan Mall. And Papa Luigi’s pizza was the only pizza we had in a 20-kilometre radius. For us to get downtown there was either the intercampus bus or Mississauga Transit, which only started running, in ’75, a shuttle service up to Sheridan Mall, and then… Ha, we called it the scenic route. For us to get to Islington so we could take the subway downtown was a two-and-a-half-hour bus ride that just wound its way through all kind of areas. There was no bridge across there on Burnhamthorpe. To cross that river, you had to get down onto Dundas. That was the only bridge across. There used to be a small A&P, not even a supermarket, just a small A&P grocery on the other side of the bridge. We would walk down; it was a 20-minute walk for us to go and buy milk. It was nothing on campus. You have no idea.

“But it built a sense of community. For people who lived on campus, we were family. Everybody knew everybody else. The only residence was that little group of townhouses there at the north entrance. That’s where people lived on campus, was in those houses. I was lucky: I was put in McGill House, which no longer exists. It was on Mississauga Road, just there at the south entrance, and there was another couple of residences in between there and the north houses, which were farmhouses that the university had bought over. One was called Hasty House, which we used to nickname ‘Tasty House’, because it was only girls that lived there. That was across the street from Colman Place. Even Colman Place used to be a residence, but that was converted too.

“All three houses had outdoor pools! If the building has not changed any, when you’re inside Colman Place and you’re looking out towards the path that runs between North and South Building, it used to be right outside that thing. Hasty House had its own pool, McGill House had its own pool. But they’re long gone. Long gone.

“We were like a little community, a little village, you know, just 300 or 400 people on residence, and everybody knew each other. Because we were in essence just this little island community in the middle of nowhere. It was a simpler time.”

That’s how Robert Sabga, Medium II’s first editorial cartoonist and a DJ at Radio Erindale, described “the good old days” at what was then known as Erindale College.

“Nostalgia” would be an uneasy classification. Nostalgia elides inconveniences. But the difficulties of the time were indeed alive to Sabga, as they were to Mark Brown (Medium II operations manager), Ralph Szalay (DJ at Radio Erindale and finance commissioner of SAGE, the Student Administrative Government of Erindale), and Bruce Dowbiggin (Medium II’s third editor-in-chief), all of whom were on the campus of 3,000 students in 1974, the first year Medium II was published.

Among these inconveniences were the bus service—the crawling Route 1 ran from the west end to Islington, and later was altered to bypass Erindale College to cut 10 minutes from its route; the lack of food—the pub didn’t serve proper meals, and after the North and South cafeterias closed, you were stuck with vending machines and lumpy coffee; and even the architecture—the South Building (now Davis) had just been built, and was immediately recognized as “a mass of concrete, nothing very subtle or very light—it was just heavy, Stalinist”, in Dowbiggin’s words.

Yet there was a life in the campus that isn’t always apparent today. When South was finished, Sabga recalls, the members of SAGE took one of the mixing pans in which they moulded the cement panels that clad the outside of the building and turned it into a raft, the SS Erindale. They launched into the pond outside the doors and made it about 15 or 20 feet in before they sank. “On its maiden voyage it went down with all hands,” he says. “So that’s still down there.”

The North Building was then, as it is today, a haven for English students. You could go there and hear academic discussions “that sounded like they were of some other planet, and if you didn’t agree you were ostracized,” as Szalay, an English specialist himself, put it. Also housed in the North Building was the radio station, which had begun in 1968 as “a bunch of kids playing records on a record player over the PA system”. The first principal, John Tuzo Wilson, liked that idea himself. It was he who bought the first control panel. Officially, it was for the communications courses, but somehow it ended up in the care of the radio station.

Meanwhile, Friday and Saturday nights were always pub nights in what had just been dubbed the “Blind Duck” (for reasons none of them recalls, although a naming contest and cartoon character are vaguely remembered). Brown, who cleaned the pub’s washrooms one year—in those days you could pay tuition on a summer job and a weekend job—remembers there always being about four inches of popcorn on the floor and, curiously enough, always more full beer bottles left in the women’s than the men’s.

The pub had multiple purposes, and was even used for classes sometimes. Once, Szalay was late for a class in which he had to give a thesis presentation—he was getting his notes together in the pub. When the prof asked his friend Bob where Ralph was, Bob replied, “He’s a little under the weather.” He then quipped, “I’ll be joining him under the weather after the class.” To Szalay’s surprise, the prof and the whole class trooped into the pub, got themselves some beers, and did the presentations there. It was a great time; it was casual.

It was in this milieu that the Erindalian, the campus’s first newspaper and Medium II’s predecessor, had been founded and was still operating, in the cottage known as Colman House.

THE OLD GUARD

The ill-fated Erindalian had been founded in 1969 by Bob Rudolph and Doug Leeies. The newspapers of the day—before the Internet and its provision for all kinds of venting—were more political. People were often a part of them, Dowbiggin remembers, because they believed in “the revolution” or in a particular political cause. But speculation in the Erindalian’s case is obscure. All we can say is that it was unique. In a 1997 history of the publication that is now history itself, Medium editor Duncan Koerber, now a writing professor at York, quoted Leeies: “It all started on a shoestring budget upstairs at Colman House. Erindale was a blank canvas for us. Nobody else was doing what we were doing. We were cutting our own trail.”

Here Szalay, then a DJ at Canada’s First Radio Erindale, met Gregg Michael-Troy, Matt Shakespeare, Dowbiggin, and other students who would soon become influential in campus media.

But both CFRE and the Erindalian were in trouble. One day Szalay, who wanted to go into program production, discovered that the radio station’s tape decks didn’t work. He made the mistake of asking why: because there was no money to fix them! He found out from the people running the Erindalian that they had the same problem. In fact, they were short an issue or two because they didn’t have the money to print them. They were running out of cash, and the editor-in-chief quit that spring, leading to the folding of the publication. They were going to disband CFRE, too. Desperate, they all decided that one of them should run for communications coordinator of SAGE the next year and sort it out. Because he’d asked in the first place, Szalay was voluntold.

Once he had been elected, he discovered that the funding for both campus media had been waylaid—not stolen, but used for things it hadn’t been allocated for, including vans for the pub. When it came time for SAGE to present their budgets to the downtown council—they were linked back then—Szalay and another member of SAGE proposed a separate account for the $26,000 that was to run Erindale’s campus media. Their communications commissioner, Michael Sabia—son of feminist Laura Sabia and CEO of Bell Canada from 2002–08—agreed, and the groups got what they were budgeted for that year.

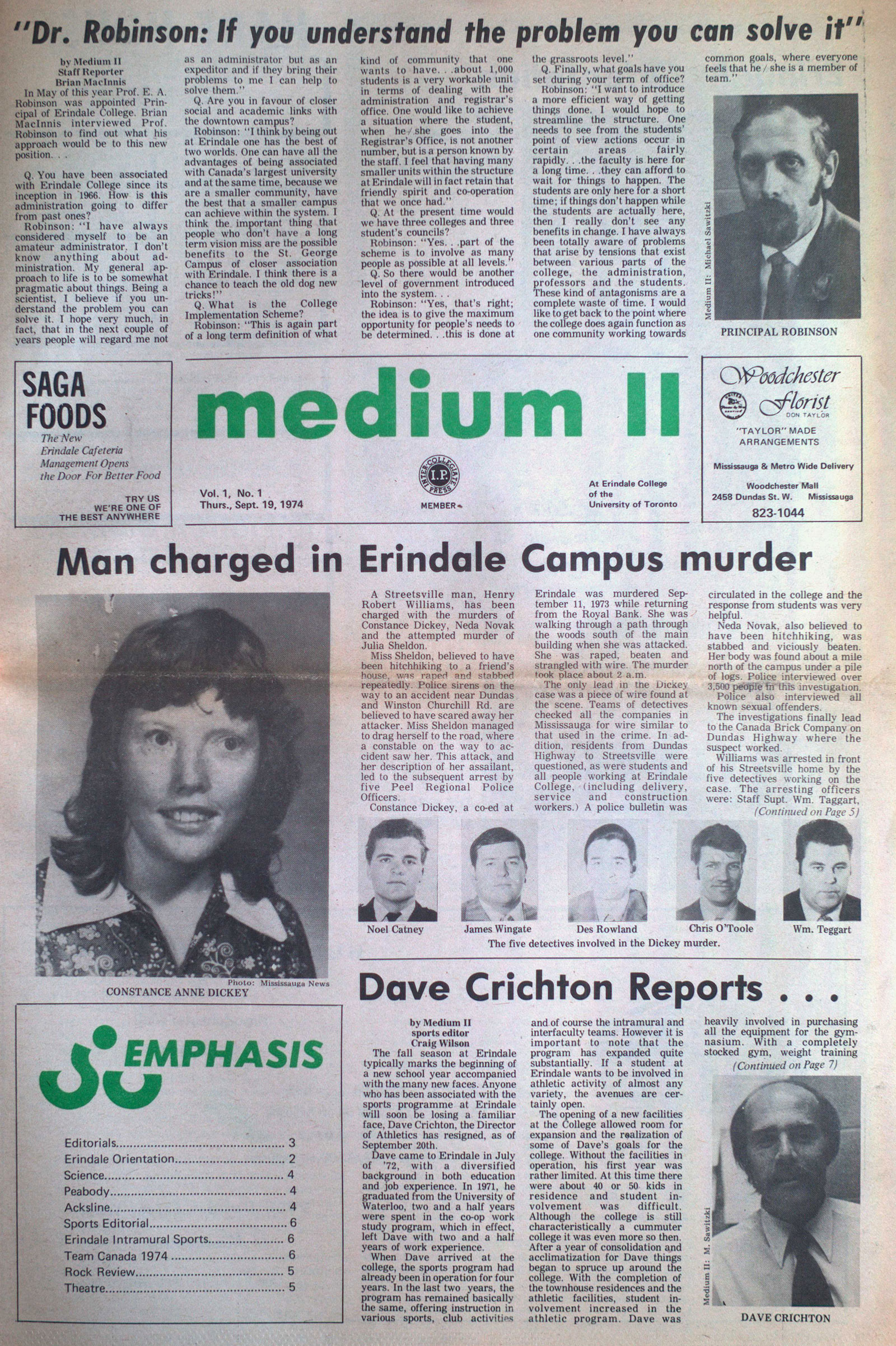

But it was already too late for the Erindalian. It had fallen apart. Using the last of its budget, Gregg Troy (as he was known for short) pulled together a few people and published the very first issue of Medium II, with perhaps the most striking headline it has ever had: “Man charged in Erindale Campus murder.” (That young woman was Constance Anne Dickey, who, to our knowledge, has never been memorialized as a victim of violence at U of T.) Troy and his team’s very tangible proposal worked: SAGE approved of the publication and added it to their portfolio and budgeted for it. So the first year of Medium II, the student government was in charge.

THE MICROCOSM IS A HOTHOUSE

Even Medium II’s name, which was finally changed to the Medium in 1995, was a source of contention. Troy wanted to call it the University Journal, but that was taken for a literary publication. It’s an irony that has never been forgotten that the “II” signified that it was secondary to the first medium on campus, CFRE, considering that Troy, by all accounts, resented the radio station to the core.

Indeed, Szalay and Brown in particular remember Gregg Troy as difficult to get along with. “I gotta tell you about him,” says Szalay. “He was one of those people. At first he had company manners. He was a nice guy, but after a while he was a royal pain to get along with. When I agreed with him, then he was great. When I didn’t agree with him, aw, he could be so cruel.”

Of course, it has to be accounted for that Szalay was from the student government, and, as news editor Mark Brown recalls, “Everything in the microcosm is a little bit of a hothouse. At school, you live in a little bit of a bubble and the temperature gets turned up, and it’s the whole world.” Money was a big issue. It was tight, and sometimes a group needed something that hadn’t been budgeted for, such as a punched tape machine used in the offset lithograph printing process. Hence, “The budget process was always quite intense, because everybody was really passionate,” Brown adds. “The paper wanted some money, and someone else wanted this, and the clubs wanted this…”

Considering that, to Troy, Szalay both represented the money and the competing media—he was still a DJ there that year—Radio Erindale became a particular thorn in his side. In editorials and letters, Troy described CFRE as “fatuous”, and anything that they got that Medium II didn’t get was another source of disagreement. One year, CFRE held a Christmas party on the main floor of Colman House, and it was licensed. Troy came over, says Szalay, “and he made such a fuss! He was pouring alcohol on people’s heads.” Szalay came up beside him and told him to pipe down, and Troy was ribbing him, “being really antagonistic. He was like, ‘How come the Medium II wasn’t invited?’ I says, ‘Well, it wasn’t something I had to do with! Radio Erindale had a Christmas party for their staff.’ I don’t know if Medium II had one.”

Yet Gregg Troy was a genius at what he did. With nothing for a model but the defunct Erindalian and perhaps the Sun, and with no motivation but his own, he ran the paper to a standard that has rarely been matched in subsequent years. One week, “He and Johann Barr managed to get the van,” Brown recalls, “and they went down to Quebec City and interviewed René Lévesque, before he took over the government. So it was early when he was getting involved. And they took a photograph and, quite frankly, I think it’s one of the best photographs that’s ever been taken of René Lévesque. Gregg did a whole two-page story on the interview, and that was a really key, important thing to him. We didn’t know you couldn’t do something, so we went ahead and did it anyways.”

He also points out the article’s prescience concerning the discussion surrounding Québec today and the Charter of Values. One question was, “How did French culture survive?” Lévesque replied, “That’s a hell of a good question, because we’re in a transition period. What kept the culture going, at least the language and some very minor cultural achievements, was mostly the fact that we were a rural society, basically a peasant society tied to the Church and tied to tradition.” Particularly stunning to Brown is that Lévesque would describe as a “peasant society” what was an important rural vote. And there it was, exclusive to Medium II.

Troy’s staff, too, had a hand in the paper’s success. Szalay had recruited Sabga as cartoonist (Sabga had been his high school’s cartoonist in Barbados), and some great cartoons were produced. When the campus opened up the first townhouse residence—superseding the farmhouses it had previously converted—he had fun with the idea of the quaint community, drawing Hobbiton with its little hillocks and doors in the hillocks. When the mayor of Mississauga who (if it can be imagined) preceded Hazel McCallion suggested separating Erindale College and creating the University of Mississauga, the staff got wind of it and satirized it with a huge pair of scissors cutting the link between the two.

Several other stories were of high calibre. When Formula One was running out of Mosport, Brown called them up and asked for a press pass on the grounds that he was from a university newspaper—in fact he just liked cars. Boom, press pass showed up, and he covered a day of racing. Medium II also sent him to the old CNE stadium to document a Blues game, and he called it in to CFRE so they could broadcast it. Because of Brown, Medium II was also one of the first papers to do a journalistic ride-around with a police officer, which he did one evening with Peter Young of the Peel Regional Police. When the police saw the write-up, they placed full-page ads in the paper to recruit officers on campus.

And many other names were involved in the elaborate production, of course, which involved everything from physically pasting articles onto the boards to driving the rickety van out to the printers in Acton. Certain names recur in the conversation of Brown and Szalay: Heidi Putzer, Vivien Anderson, Tom Maloney, Jackie Tremblay, Linda Kuschnir, David Leslie…

One frustration of Gregg Troy’s was the difficulty of getting writers, if not readers. Sometimes, in order to spark a debate, he would write a letter under a pseudonym, such as Peabody. It wasn’t transparent, but it exemplifies the lengths to which he would go to light a match under someone’s butt and get things moving. He also invited Szalay to contribute, despite the tension between them. And yet—another of Troy’s contradictions—he would often take the teeth out of an article.

“He certainly drove issues, there’s no question about it,” says Brown. “He was the driver to get it going, and tremendous effort on his part to do it.”

Even Szalay concedes that it was worthwhile putting up with him, because he was doing good work: “And his legacy, since it still exists, is a pretty darn good legacy.” Here Brown interjects: “Oh, yeah. It’s the mountain you’re standing on.”

“Yeah,” says Szalay, “there wouldn’t have been a Medium II without him.”

THE MOUNTAIN WE’RE STANDING ON

If we zoom out, the campus was, in some sense, unchanged.

It was still the same Erindale College, a tiny, unserious place in the middle of nowhere where, Szalay remembers, there was stretcher service to the pub from the blood donor clinics, where the student government was “loosey-goosey”, where there was one pizza place in a 20-kilometre radius. When Brown moved to Mississauga from Windsor in 1967, he recalls, they were taught in grade 8 geography that Peel County was one of the largest producers of dairy products in the Commonwealth (“and I don’t know if you could find a cow in that region right now”)—and south of the 401, there were no houses till you got south of the railway tracks, everything was extensive country, and Highway 10 had two lanes.

And the campus was still homey. Mike Spigel, for whom Spigel Hall is named, was then just a professor with a big pipe, on whom students played pranks, turning his own behavioural psychology hypotheses against him (“But he was one of the originals, that’s for sure”). Desmond Morton, later the dean, was a professor who was tough on spelling in essays, before computers and spellchecks. You could get pretty far on a rumour, too. Sabga and a professor once joked with an abnormally gullible TA about the dry dog food they had just come out with, which had nitrates in it to enhance its so-called nutritional value. Dogs, they said, couldn’t metabolize the nitrates, and the major part of their body fat is glycol, so when a dog got excited and began to metabolize the glycol, there were pockets of nitroglycerine in it—you’d be calling it, “Here, Spot!” and it would explode. It was a joke, but suddenly they started hearing it repeated, even off campus. Szalay took part too, faking a photo of a guy holding a leash with a charred collar on it. CBC was going to send a team down to investigate, and that’s when the professor told them to shut it down. How hard would it be to get away with that today in the face of snopes.com?

Even Principal Tuzo, world-famous for discovering continental drift, had that air of fun. Every week he’d invite people in student affairs and alumni to the grand old principal’s house, Lislehurst. For his goodbye party, they made a huge cake out of cardboard out of which someone playing a Mississauga tribe Indian jumped out to give him the key of the city. And Matt Shakespeare cooked up the idea of a giant punch bowl—Tuzo’s wife was famous for punch—that they made out of plastic and cotton, and while someone manipulated the cotton with a string to form the continents, the guy playing Tuzo fiddled with the foam in his wife’s punch bowl and said, “Ooh! Continental drift!”

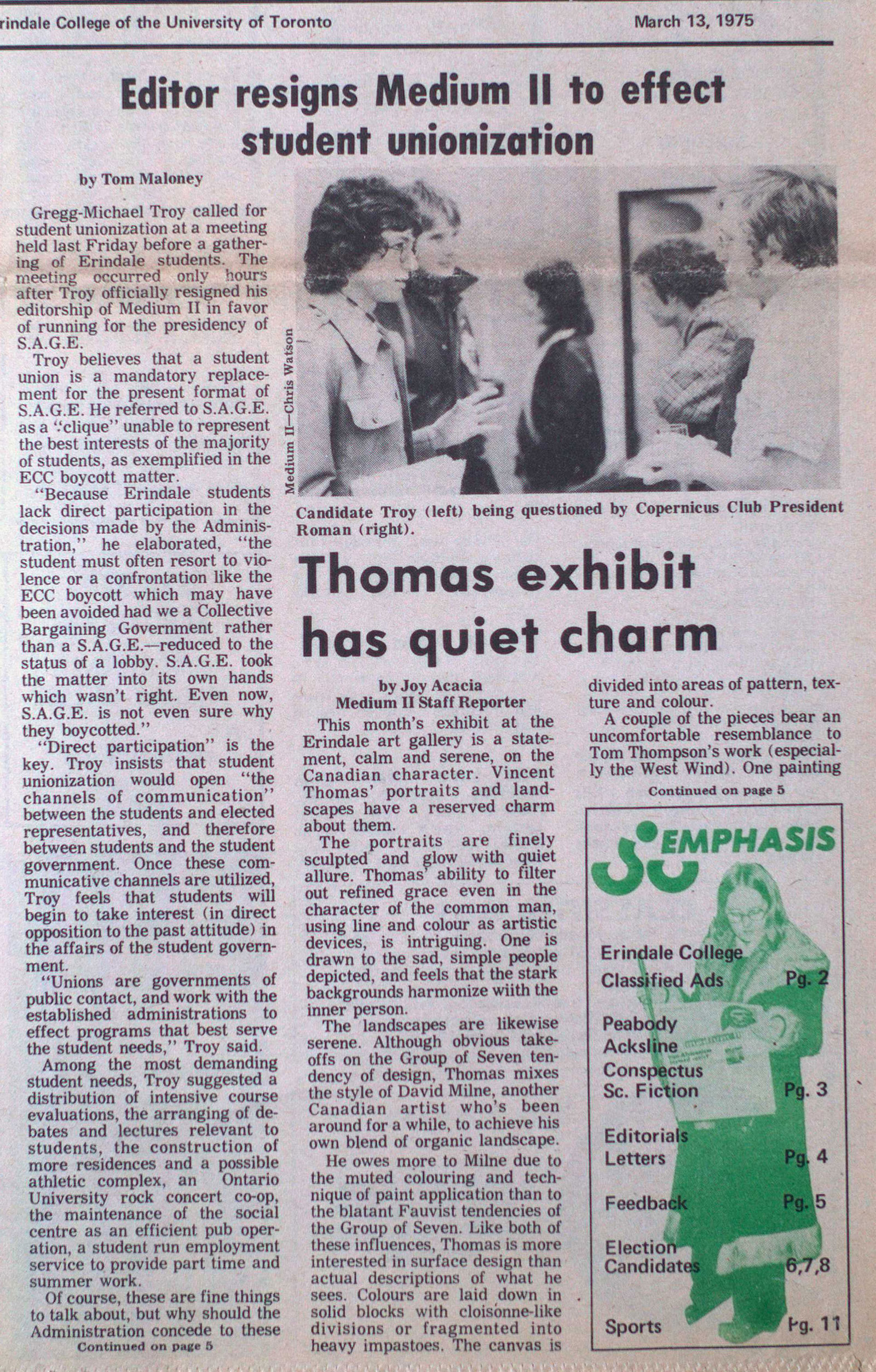

Yet something had indeed changed below the surface. That world, bathed in nostalgia or no, was on its way out. Larger-than-life figures were altering it through many channels. The same year he founded Medium II, Gregg Troy resigned, ran for president of SAGE, and killed the council “almost singlehandedly”, in Szalay’s words, to found the Erindale College Student Union, which was later renamed UTMSU. New buildings were put up, phase by phase. The architectural style evolved away from functionalism and brutalism to something more like what we see today. The residences’ outdoor pools disappeared in the process. Universities began campaigning for international students (not by any means regrettable). Erindale College began to be promoted at U of T, and enrolment began more sharply increasing across the province, even as the liberal arts degree began to slip from prestige.

They also started to formalize offices. The pub and the student government were removed from the small house Dowbiggin says they were run out of and were distributed throughout the new buildings. Medium II was shuffled to North and to a shed called Margeson House by the pub. The long-standing relationships between various organs of the campus began to crystallize. Not a decade later, after the infighting became more intense, the paper was officially separated from ECSU by a student referendum and shortly thereafter was incorporated. ECSU drafted a constitution and its priority, which could once be summarized as to “make sure the pub had lots of beer”, become more structured and set. The roles of the administration, the paper, the radio, and the union began to develop familiar scripts.

Those were indeed the formative days of Erindale College, and we are indeed standing on the mountain they built. Brown observed that there was no long tradition at Erindale at the time; undeniably, there is now, even as we look to the future and wonder on all fronts whether all these institutions—universities, radios, newspapers, and even governments—have outgrown their usefulness. At such times, the most important thing is to look back and recognize that there’s something to be said for the circumstances of uncertainty, of malleability, in which individual people can shape their world over in their vision, as they could and did then.

It may be Dowbiggin’s words of advice for journalists that ring loudest in the wake of stories like this: “Run with it! Have fun with it! Don’t feel you have to do what they did the year before. Look at the big world out there and dream big dreams, and most of all—and it’s a hard thing to do at universities these days because of political correctness—try to get the full range of opinions and attitudes that form the community. Don’t just get hunkered off and do the same as everyone else is doing. Understand that free speech is about hearing people you don’t necessarily agree with. That’s the most important thing.”

This brings back a few memories – and the discovery of several errors as well. The original houses on campus were not farm houses but suburban homes built in the post war era. McGill House was south of the south entrance road just at the top of the hill on Mississauga Road; I was a summer resident there in 1981 in what had been the den with fireplace. I can recall reading a book on my bed one Sunday afternoon and looked up to see a doe and faun through the window in the back yard deciding whether to cross Mississauga Road.

McGill House was a men’s residence and party house supreme on occasion. The normally studious residents would load most of the furniture into the basement, convert one of the bedrooms into the sound booth and blast music into the living room/dance floor. The den was for cooling off and mingling while the upstairs bedroom was for chilling out and quiet conversation. The parties were by invitation only, though if you knew someone who had been invited they could get you in. The parties ended in the late 1970s when a group of high schoolers tried to crash the party and started a fight when they were refused entry. Lou Terpstra and Holly Mungal were the disc jockeys that ran the show, later serving as DJs at the Blind Duck. The swimming pool had been filled in by the late 1970s.

Medium II moved from the old Erindalian offices in the basement of Colman Place to the North Building before moving to what had been the construction office for the South Building – Margison Hut. It was steps away from what was known as the Crossroads building (now replaced by the Student Center) and also what was called Dobratz Cottage – a rustic home for a married couple who were graduate students.

The Crossroads Building (my, weren’t they imaginative with the names for structures back in the day) was shaped like a short hockey stick. It was supposed to house a variety of stores and services with apartments for married students upstairs, but the demand for classroom and office space soon nixed that idea. The housing office (on-campus residences) was located at the end closest to the Five Minute Walk and for a very brief period in the fall of 1975 (maybe a month, possibly two) the opposite end was the first and only branch store for Round Records, a very hip record store located on the second floor of a building where Holt Renfrew now stands. I was their first customer, paying the then astronomical price of $4.99 for Pink Floyd’s “Wish You Were Here” LP. Most new releases had sold for $3.99 or $4.49 – the Floyd album was the first to test a new suggested list price of $5.98. The space later became the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce.

Colman Place had been a two story ranch home with a three car garage and pool before the university took it over as a student center. It had Murphy’s, the first pub on campus which also served submarine sandwiches, on the ground floor. This space was to have become a bar/cafe in 1977-78 but the Medium II got wind of the plans and pointed out that the campus already had a pub and a second one was simply not viable, so for years this portion of Colman Place was not open to anyone. Radio Erindale resided upstairs “broadcasting” through Bell music channels to a network of speakers in the residences and common rooms and cafeterias of the North and South Buildings. The Erindalian formerly had its offices in the basement along with a massive slot car raceway. It also housed the student council before the Housing office arranged a swap with their offices in the Crossroads building. A third of the upstairs of Colman Place was unfinished attic until Radio Erindale convinced ECSU to renovate the space into an expanded record library, recording studio and control room. The garage had been a games room (pinball and arcade games), later converted to storage and a workshop for student housing. Once the housing office moved in to the downstairs, what had been Murphy’s became a student center/event space for the residences.

Because the Toronto Argos used the football field outside the North Building as a practice facility and because Radio Erindale had a Broadcast News teletype feed, the radio station managed a scoop on the Toronto press. The Argos had just fired coach Russ Jackson and the station news director Jack Shand had been chatting up some of the players and overheard the news passing among them. Confirming it, he raced back to the station and phoned Broadcast News with the story – before the Argonaut’s scheduled press conference to announce the firing. The station was credited in the subsequent news reports – but the players no longer talked openly about what was going on behind the scenes.

A contemporary of my first year at Erindale decided that radio would be his choice of career and quit after his first year, driving from small market station to small market station until someone hired him. He later moved to CHUM Radio, City TV, then CBS News, then CNN and is now an anchor at Fox News. I knew him as John Robertson – he became J.D. Roberts, now John Roberts.

Between Colman Place and Mississauga Road was an apple orchard; it later became phase two of the townhouse style residences circa 1979. There was also an orchard on the rim of what had been a gravel pit before it was reclaimed as a sports field and parking lot. And, of course, there were the orchards that were part of Lislehurst.

There was a cottage for the artist-in-residence along the road to the Moon Rocks Lab and Lislehurst. There used to be another house behind Lislehurst and the remnants of the road across the ravine to it along with its foundation can still be seen.

There was another house to the north of the orchard in front of Colman Place, built in the 1930s or 40s, if I recall correctly, but I cannot remember the name of it. It was a men’s residence and I recall that the residents neglected to take out the garbage for some time, tossing the bags into the basement until the smell became too much for one housemate to bear. He grabbed the first bag from the pile and plopped in onto the kitchen floor before putting on his coat to take it outside. A large rat jumped out of a hole in the bag and a chase around the house ensued before the rodent was vanquished. The housing office made certain that the garbage was taken out promptly after that!

North of that was Hastie House, a women’s residence – again another rambling suburban home, with a pool.

North of that was the first phase of 53 townhouse style residences with house 52 being the lowest lying of their block of houses. I know this because I lived in House 52 one and found raw sewage spurting from the floor drain in the storeroom after returning from a long weekend in the summer. Every time someone used their toilet, sink, or shower along the block a geyser would erupt. The puddle extended into the kitchen and living room before the clog in the drain was cleared. There was no compensation offered by the housing for damaged personal property (previous years notes, some clothing) or the inconvenience.

Across from Hastie House was the campus services building, basically a garage for the tracks and grounds keeping equipment.

The first proper farm house was just to the north of the North Entrance; they ran an orchard and sold apples and apple cider every fall.

There was a walkway between the residences and the North Building, with a studio theater to the west of the North Building. Moving south on the Five Minute Walk were two portable classrooms on the west side, one of which became a general store for the residences; the other was a studio/classroom for artists. South of those was the pub.

The campus pub began life as the Watering Hole before the name was changed to the Blind Duck, partly in homage to a Mimico pub called the Blue Goose. The graphic of a duck with one eye open and the other closed should be available in the back issues. The building may have begun life as a maintenance building, then a lecture hall while awaiting the completion of the South Building, and then the pub. The interior was basic portable classroom with a stage for the bands for many years. In 1976 the student union invested in a portable DJ system and operated between sets on band nights and between periods on hockey nights. Eventually the sound system was upgraded and what had been the band dressing room (actually a large utility closet housing the water heater) was converted to the DJ booth. A few years later, Fred Luk (later opened Fred’s Not Here restaurant on King St West) upgraded the sound system yet again, added lighting effects, and renovated the interior to a mock Tudor motif adding tall tables made of giant wooden spools that had been used for thick cable. Food services were later added, along with an upscale lunch and dinner menu. There were arguments raised that the pub was being changed so as to exclude the students in favour of the faculty.

Fred’s tenure as manager also favoured dance nights over live bands and the dance music did not sit well with some patrons who wanted to drink and watch the sports rather than dance. Plus the dance crowd was divided between those who wanted rock and those who wanted disco – keeping a balance was not easy. (I DJ’d at the Duck from 1976 to 1985.)

The Blind Duck also managed to snag the English Beat after their scheduled performance at the Masonic Temple was cancelled. Toronto’s punk scene turned out in droves while most of the regular crowd stayed away. During the opening act some drunken idiot pulled the fire alarm and when the fire department arrived and saw the punks, they radioed Peel Regional Police, who threatened to shut the event down if there was any further trouble. Fortunately there wasn’t – much to the disappointment of the phalanx of police who had assembled and were ready to pounce and arrest given the slightest justification.

There was one occasion when a soldier from the Canadian Armed Forces was ejected from the pub. He retaliated, first by putting a smoke grenade in the air conditioning unit intake, and when that failed to shut the pub down, lobbed a canister of tear gas beside it, which quickly achieved the desired result. I learned the hard way that the worst thing you can do when tear gassed is to tilt your head back and pour water on your eyes – it flushes the irritant into your sinuses and it feels worse than ingesting an overly spicy lump or wasabi or extra strong horse radish. The military police quickly took control of the investigation from Peel Regional Police and shut down any publicity of the incident.

With the construction of the South Building, the Meeting Place became available for concerts and other events. I saw Rush there on January 4, 1975 – my ears rang for days afterward. It also served as the venue for Oktoberfest for a number of years because of the increased capacity. I also recall the South Building cafeteria being used for the occasional event – residence dinners and faculty banquets with a live pop instrumental band.

Square One was in existence prior to 1974, though a fragment of what exists now. It had a Woolco and Sam The Record Man. The nearest large supermarket was at Erindale Station Road and Dundas St. Luigi’s was not the only pizza shop for 20 miles – there were several, but none of them of any quality – except for Gio’s Pizzeria, originally at 2645 Liruma Road before they moved to Streetsville. Sadly, Gios is no longer in business. Radio Erindale rans ads for Gios and he probably earned back what he paid us in what we ordered from him. Once Erin Mills was developed the supermarket situation improved – I recall living across from one at South Millway and Erin Mills Parkway in 1980. The plaza also had the nearest McDonalds and I can recall making the trek from the campus to the South Millway Plaza through what was then a small wooded area alongside the creek/storm water culvert that ran from Erin Mills Parkway to Mississauga Road.

The murder story on the front page of the first Medium II came back to haunt the student union of 1977-78 (Rob Mowat ticket). In trying to think up a catchy slogan for the orientation T shirts, they settled upon “Sex and Violence at Erindale College” and had the shirts printed up and distributed to the frosh and team leaders. Then the phones began to ring, first from the administration who had not been consulted about the slogan and were livid over the choice of wording, then from the faculty and staff who took offense at the slogan, and finally from outraged parents who spotted the shirts when their precious darlings wore them home. The murder of Constance Anne Dickey was still fresh in the minds of many people – but not the minds of the student union when they thought of the slogan.

Mississauga Transit did run a shuttle bus to Erindale Station Road but it was far too small a bus – about the size of a Wheel Trans van – and too infrequent. Many students made the trek to and from Dundas Street and Mississauga Road instead, which was a safety hazard in the winter as the sidewalks along Mississauga Road were not plowed. Eventually Route 1 service to the College was restored.

The “exploding dog phenomenon” spread its ripples far and wide. A few months after it began dog food manufacturers began to advertise that their product now had lower levels of nitrates. Seriously. The originators of the hoax were worried for a time that they would be sued by the dog food manufacturers.

Ralph Szalay directed me to this article earlier this evening. I went by the name Rick Harrison during my time at Erindale (fall 1974 – circa 1979) and spent far too much time at Radio Erindale, ending up working in the music industry for most of my life (26 years at Sam the Record Man). The tribute issue to the Medium mentioned a tribute that I wrote to John Lennon for the Medium but I also wrote a feature article on CFNY 102.1 and the state of radio, plus the odd record review. I also ran for President of ECSU 77-78 as Wellington Womble… but that’s another story.

An encyclopedic comment! It was fascinating to read. Had I had a few more of the contacts I now have when I was writing this article, it would have been expanded (and refined). Thanks for stopping by and responding so thoroughly.