From September 11 to November 28, the Blackwood Gallery will be home to a portion of Traffic: Conceptual Art in Canada: 1965-1980, which includes a mosaic of conceptual art pieces that shed light on the Halifax art scene. Despite the multitude of pieces, installations, and photographs, there is one word that encapsulates them all: idea. Though the ideas behind some of these pieces are quite confusing, it’s not necessarily a bad feeling to have; confusion can lead to an interaction with artwork, and that’s half the battle. If you really look at the pieces it somewhat takes away that confusion, and it’s replaced with a curiosity that begs the question: what is conceptual art?

Conceptualism is a movement deeply marked by the 1960s post-war unrest, and has remained a global phenomenon ever since. Liberation and rights movements, as well as the advancement of new technology, all played a part in shaping the new wave of conceptual art. Yet at the heart of the conceptual art movement is not mere expression of the individual; it does not require special skills or technique, but is first and foremost an idea.

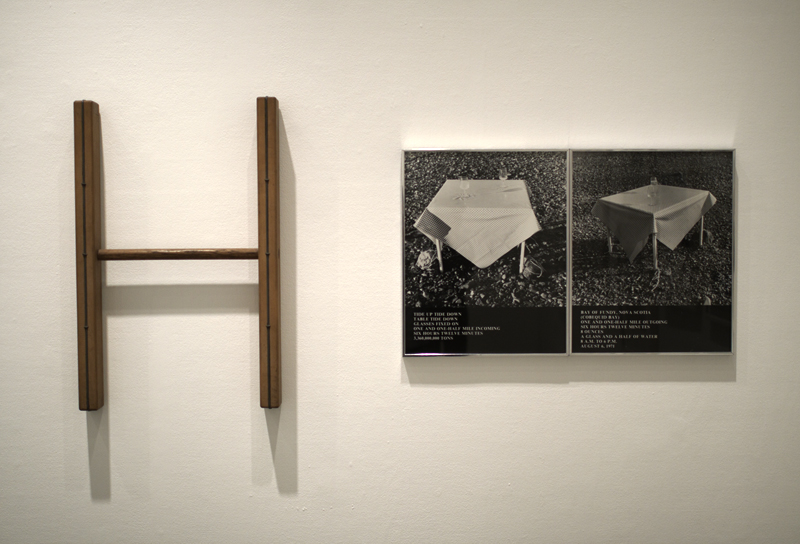

The exhibition is divided into three sections: on one wall, black-and-white as well as colour lithographs hang; on another are mostly representations of squares; and on a third, canvases filled with text. Upon entering the gallery, you find a series of large prints hung up on the small stretch of wall directly behind.

These silver gelatine prints are just calling for attention: a naked man stands in the first one, his right arm raised, his chest covered in anti-bacterial surgical scrub, with no emotion in his face. There are several more large black-and-white prints, and in every photo the same man maintains his cold, blank stare. There he stands, in the nude, with the vulnerability of his nakedness against the stark, cold background. Is this a representation of someone going into surgery? It’s scientific; but is it art? Theodore Wan’s Bridine Scrub (for General Surgery) is definitely a way to catch your attention.

On the adjacent wall hangs Joyce Wieland’s large lithograph entitled O Canada. The entire print is made up of rows of bright red imprints of a woman’s lips. The lips change in size and shape from one to the next, and are literally imprints of the artist singing “O Canada”. Like many of the pieces in the collection, this print was created at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, and NSCAD had in fact become a centre of international conceptual art activity between 1969 and 1980. Out of that famous school sprung innumerable artistic minds, flourishing among the new era of conceptual art.

On the same wall hangs Vito Acconci’s Trademarks, another black-and-white lithograph that is not for the faint of heart. It’s a large print of a naked man on one knee, contorting himself and biting his own thigh. Next to the lithograph, large blotchy ink imprints are separated by stream-of-consciousness notes scribbled in messy marker. The imprints are self-inflicted teeth marks on the artist’s own body. Through pieces like these, which depict rebellion and newness, the core of the conceptual art movement is brought to the fore. These images force us to ask ourselves, “How is this art?” Vito Acconci contorts himself in order to get a better bite at his own thigh. The scribbled notes offer us a look into his consciousness, but they offer no answer to the question, “Why is he doing this?”

The vitrines arranged throughout the gallery help answer this question. They are filled with notes, photos, old letters, and sketches, all written by the artists in regards to their work. Getting a look into the artist’s mind can be a strange experience; many of us never stop to think about the people behind the work, only the works themselves. Yet we can always ask questions to find out more. What was Dan Graham thinking while creating his piece entitled Video-Architecture-Television, as he stood naked behind a video camera, capturing a moment in time on film, while at the same time he himself was being photographed in his nakedness? What is he trying to say with this piece? It is conceptual art, after all; does it even need to make sense?

Walking quietly, looking at photo after photo and piece after piece, visitors might be asking themselves all these questions. We can only guess that the conceptual artist’s goal in the first place was to provoke just such thoughts. These artists reject tradition, line, form, colour, and composition, and create something artistic out of something mundane. They believe that anything can be art. Is this why the pieces can be so off-putting? It’s certainly not what we’re used to; the pieces range from minimalist to disturbing, even. But after all, we’re the ones who choose to look.

The lithographic section of the exhibition spans the entire right-hand wall of the gallery, and adjacent to this is a wall filled with various kinds of squares. These representations range from small sketches to large watercolours, and even a wooden square. These pieces are more what we’re used to when faced with the idea of “modern art”. On the next and final wall, there hang pieces which are composed entirely of textual representations, including a large white canvas, upon which the phrase “I will not make any more boring art” has been handwritten over and over again. John Baldessari’s piece embodies the desire of all artists with just one (simple?) phrase. Unable to make the journey to NSCAD where he was commissioned to create an on-site artwork, Baldessari suggested that the students write the phrase “I will not make any more boring art” over and over again on the gallery walls. In one of his letters in a nearby display case, Baldessari emphasizes that the students must inflict this punishment upon themselves of their own free will. Now, next to this letter, a black-and-white photograph showcases a girl standing against a large white wall, writing the phrase in tiny, handwritten letters. Conceptual art may be strange, confusing, doubtful as art, or downright disturbing—but one thing’s for sure: it isn’t boring.