What do you miss most during this pandemic?

For many people, it’s seeing friends, partners, and family members they do not live with. For others, it’s going outside without a mask and breathing in fresh air, grabbing a cup of coffee every morning, and regular campus life.

For those of us who are not particularly vulnerable to Covid-19, our concerns can seem trivial compared to the life-threatening dangers the at-risk and elderly face.

A study from MIT finds that our craving for socialization during social isolation resembles the food cravings we feel when we’re hungry. This study, “Acute social isolation evokes midbrain craving responses similar to hunger,” by Dr. Livia Tomova, Dr. Kimberly L. Wang, and their team, was published in Nature Neuroscience on November 23, 2020.

The study involved 40 healthy participants who spent 10 hours without any social contact or social stimulation (e.g. phones). According to the paper, they spent this time in an MIT room “containing an armchair, a desk and an office chair, and a fridge with a selection of food, snacks, and beverages.”

The only social contact they had was with the researchers in case of problems, or notifications through a Slack channel. After this, the participants reported “increased social craving,” loneliness, “discomfort and dislike of isolation,” and “decreased happiness.”

“There were a whole bunch of interventions we used to make sure that it would really feel strange and different and isolated,” says Rebecca Saxe, Professor of Brain and Cognitive

Sciences at MIT and senior author of the study. “They had to let us know when they were going to the bathroom so we could make sure it was empty. We delivered food to the door and then texted them when it was there so they could go get it. They really were not allowed to see people.”

After this isolation period, the participants, who had previously been taught how to enter the MRI machines, did just that. Saxe explains that “normally, getting somebody into an MRI machine is actually a really social process. We engage in all kinds of social interactions to make sure people understand what we’re asking them, that they feel safe, that they know we’re there.”

However, in this case, to avoid interfering with the data “the subjects had to do it all by themselves, while the researcher, who was gowned and masked, just stood silently by and watched,” says Saxe.

For the second part of the study, the participants fasted for 10 hours. They reported “increased food craving,” more hunger, more “discomfort and dislike of fasting,” and “decreased happiness,” compared to how they felt before fasting.

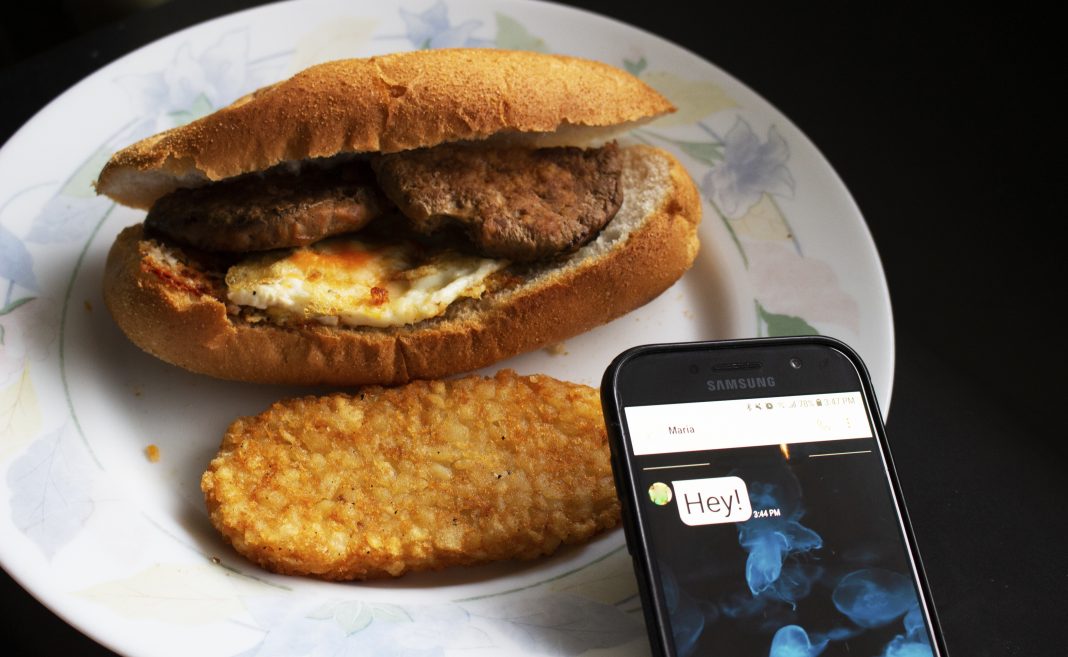

After this, the researchers took another set of MRI scans. They found that the substantia nigra, the region of the brain linked to craving food and drugs, gave off similar signals when the participants saw photos of people happily socializing and when they saw photos of food after fasting. There was also a correlation between the strength of the brain signal and how strongly the participants rated their craving for food or social interaction.

“People who are forced to be isolated crave social interactions similarly to the way a hungry person craves food. Our finding fits the intuitive idea that positive social interactions are a basic human need, and acute loneliness is an aversive state that motivates people to repair what is lacking, similar to hunger,” says Saxe.