For the past four years I’ve studied English at UTM, and for the past four years, I couldn’t tell you why I did it.

No one tells you why you study humanities when you first go to university. No one gives you a little handbook or even a secret handshake. What you do get is a question from your friends and family: “So… where are you going with that?”

Chances are that most students entering the HBA stream at UTM don’t have much of an idea either. In fact, the humanities as a discipline seems to lack the manifesto or teleology present in other studies. Sure, English students want to understand literature, but they can read books on their own time. Why study stories in a university? And why study classics or history or gender issues? More importantly, is there an end goal for the use of that knowledge?

There’s a growing sense that the humanities have no point. Aside from the chants at Frosh week, the jokes in our cultural lexicon are endless: humanities majors are stoners. They’re lazy rich kids with Apple computers and the sense of entitlement that only comes from never doing a hard day’s work. They’re headed for employment at Starbucks and McDonald’s, and they probably said something bad about your haircut behind your back. They’re not perceived well, is what I’m saying.

In 2009, The New York Times published an article by Patricia Cohen titled “In Tough Times, the Humanities Must Justify their Worth.” The article cites shrinking enrollment in humanities programs and suggested that humanities study had become a luxury suited more to “the province of the wealthy” than the rest of us that actually needed to earn a paycheque. Humanities supporters have not been silent to these criticisms: Martha Nussbaum’s Not For Profit argues that the humanities degree is vital to a democratic society that requires more than profit to succeed, but also things like free thinking and cultural knowledge. And last February, Editors Daniel Coleman and Smaro Kamboureli assembled 12 essays on the subject of the changing nature of humanities research in a market-driven university environment. The book is called Retooling the Humanities: The Culture of Research in Canadian Universities.

On July 23, Robert Fulford of The National Post criticized Retooling the Humanities for perhaps being indicative of problem with current humanities education. Fulford writes: “The scholars never say what they mean by ‘the humanities’ or why they are worth saving.” Reading his article, I’m inclined to believe him. Humanities professors, in my experience, are dedicated to their individual field. They’re brilliant, but when you ask them about the value of the humanities, they refer to the value of their study. Rarely does someone give a definition, and more rarely still do we say why it’s important.

Well, as of June I have a shiny new humanities degree, so let me give it a shot.

Most people assume that the humanities teach people how to think. Critical reasoning and analytical thought are lauded employable skills currently lauded by the humanities departments. In fact, most of the humanities majors have those very terms on the UTM Career Centre website.

To be fair, it seems that this theory is true to some degree; for example, Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses, the same book that found 36% of students don’t gain a significant improvement in total learning after four years of university, found that the humanities students showed the greatest gains in critical reasoning than any other field of study (the book suggests that these gains are meager on the larger scheme of things, but that’s another article). But the learning of critical reasoning is not the point of the humanities education; it’s a tool required for the type of thinking students do. It’s incidental in the same way that my calloused gamer thumbs are incidental to my real goal of having fun on the Xbox. If critical reasoning was the point of my English degree, I probably could have learned it in a few logic courses. It’s also a sort of folk belief that humaniiets teach good writing, which in my experience generally isn’t true.

“Damnit, Amir!” you might say. “This article has gone on for too long already! Get to the point or get out: what does the humanities degree do?”

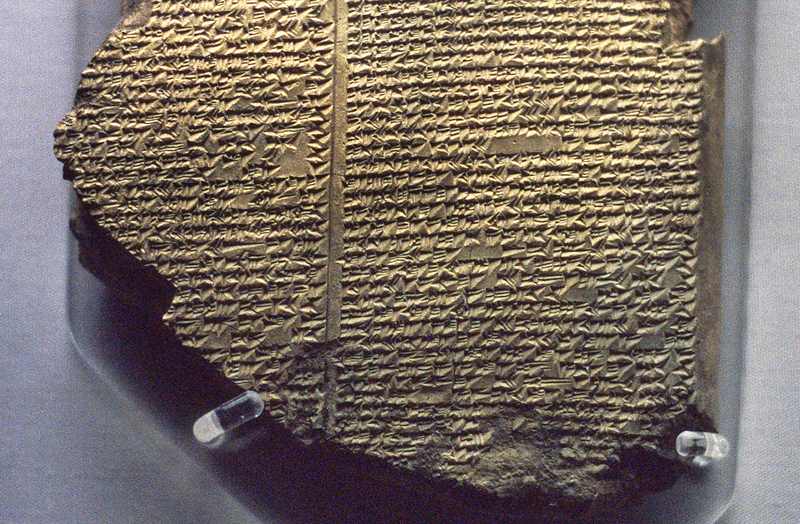

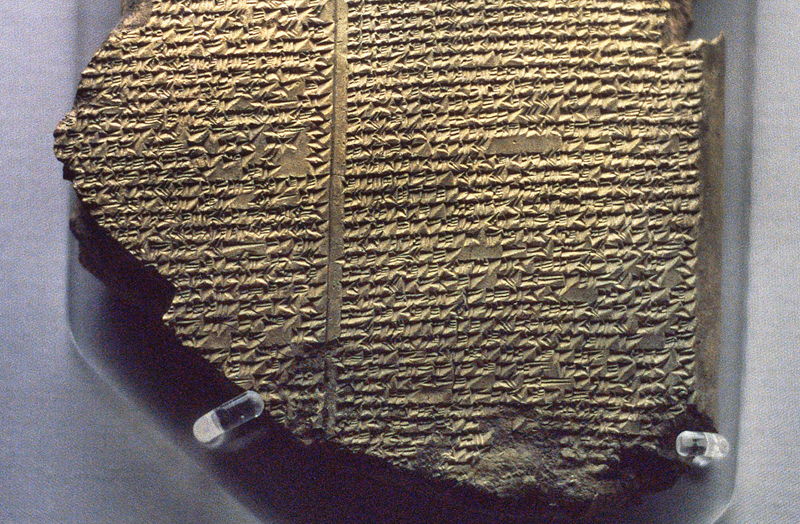

Let’s start with some history: the humanities as a field started during the Renaissance and the advent of humanist philosophy. These fields were known as the humanitas, because people hadn’t figured out how to speak English in universities yet. The humanitas covered grammar, rhetoric, poetry, history, and moral philosophy. These fields were responsible for cultivating the individual and allowing them to participate in an active life of citizenry. The humanitas were a common education that allowed people to communicate with each other. In the modern context, humanities covers philosophy, history, classics, fine art, languages, gender science, political science, cultural studies, and even strands of geography and psychology. It’s a grab-bag of subjects influencing and tripping over each other even as new subjects come into being—subjects we didn’t even know existed. I doubt John Strachan, the first President of King’s College in 1843, predicted that we would be studying gender science in 2011. I doubt he’d think there was even anything to learn in the field.

And as the humanitas expanded into the modern humanities, its function has changed as well. It’s become a lot broader, and at the same time incredibly simple. Humanities students, as the name suggest, study humanity, and they do it by studying the cultural elements unique to our species, the things that make us unique in the known universe.

Where the sciences look out, the humanities look in. Both are important. We understand the world through science, and through humanities we understand ourselves. Without looking in, we cannot know ourselves, where we are going, or where we should go. If we cannot see ourselves, we can- not know what is wrong.

This topic is a lot more nebulous and complicated than I can give justice in the space of a newspaper. In fact, instead of elucidating the value of a humanities degree, I may have just made things worse for all the first-year, non-declared HBA students out there. So, to patch things up a bit, let me give my reasons for studying English at UTM, and why you shouldn’t be ashamed of it.

Because I believe that we are more than squishy clockwork. Because I believe that life and meaning and justice are more than pretty words. Because I believe that we can develop our- selves, and that we must develop, I studied literature.

Also, some of the books I read had sex scenes. Good sex scenes.