Seven candles stand on top of a Kinara, the Kwanzaa wooden candle holder. From December 26 to January 2, one candle will be lit each day until the seven candles—collectively called the Mishumaa Saba—flicker altogether on the seventh day of the week of Kwanzaa. Every year, as Christmas celebrations wrap up across the world, African Americans, African Canadians, and the global African diaspora prepare the Kinara for Kwanzaa.

Maulana Karenga, a professor of Black Studies at California State University, created Kwanzaa in 1966, a year after the Watts riots, in Los Angeles, California. The riots—in the predominantly black neighbourhood—left thirty-four people dead, a thousand injured, and millions of dollars’ worth of property destroyed.

At the time, L.A.’s beaches were segregated by colour. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had just led demonstrators on a march from Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery, Alabama which had ended with bloodshed.

This environment gave birth to Kwanzaa.

The holiday is not religious and is not meant to replace other religious holidays such as Christmas. It is a holiday created to celebrate, to remember, and to uplift.

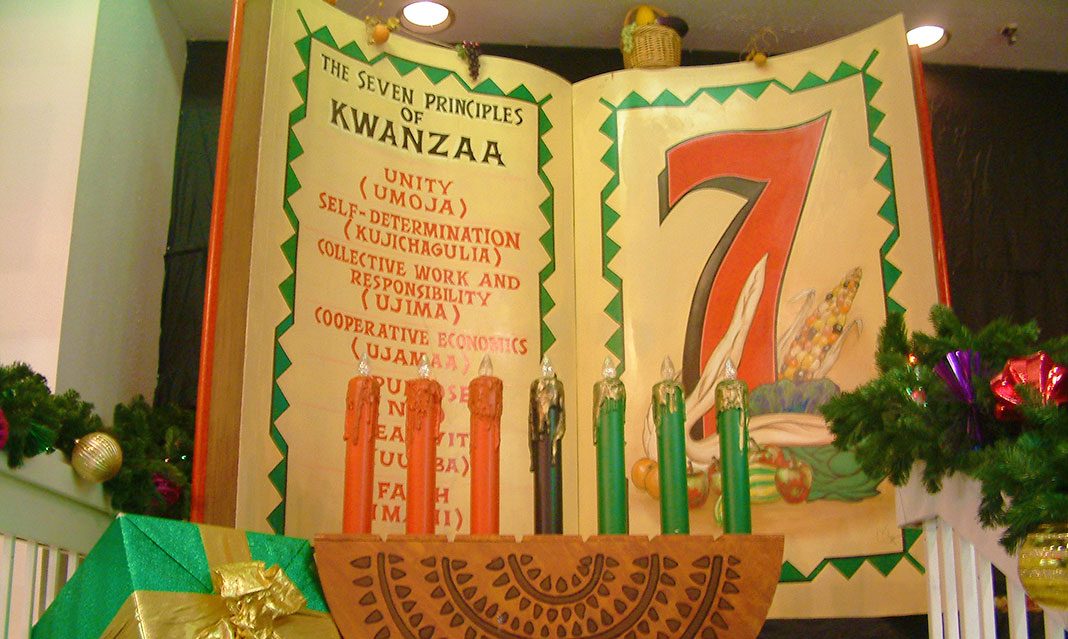

The word Kwanzaa comes from the Swahili phrase ‘matunda ya kwanza’ which translates to first fruits of the harvest. Kwanzaa is spelled with an extra ‘A,’ which, as the seventh letter of the word, represents the seven days of Kwanzaa.

During the week-long celebration, the seven principles of African Heritage (Nguzu Saba) are celebrated: Umoja (unity), Kujichagulia (self-determination), Ujima (collective work and responsibility), Ujamaa (cooperative economics), Nia (purpose), Kuumba (creativity), and Imani (faith). These principles are meant to uplift the community and the individual.

On the day of Kuuma, the sixth day of celebration, families will hold the great feast. Stewed Congo rice and peas, fried chicken, baked potato pie, corn bread, Callaloo, Joloff rice, and vegetable Ital stew are dishes one can find during the great feast. On the seventh day, the day of Imani, gifts (zawadi) are given to children.

Last year, the Toronto sign at Nathan Philip’s square was lit in red, black, and green to commemorate the seven days of Kwanzaa. It was the first Canadian proclamation of Kwanzaa in Canadian history. The Canadian Kwanzaa Association (CKA) also held a celebration at the Peace Garden. DeWitt Lee III, the host of last year’s celebration, stated that he hopes Kwanzaa will become a yearly event.

“These proclamations give the people of Canada sort of an authority and a right to be able to celebrate and to truly leave a legacy for future generations to come,” said Lee.

This article leaves out an awful lot of controversial parts of Kwanzaa, and also there are just plain inaccuracies here.

“The holiday is not religious and is not meant to replace other religious holidays such as Christmas.”

Wrong — Karenga specifically created it as a black alternative to Christmas because he, quote, thought “Jesus was psychotic” and that Christianity was a white religion that black people should shun. This is all googleable information.

Karenga “mellowed out” his position when he was told that if he took a more universal, non-antagonistic approach then more black Christians were likely to actually celebrate it. Well, maybe, but it’s still basically a dead holiday. And it’s offensive.