To be honest, I can’t recall how it began—the sensation that something was changing in our culture.

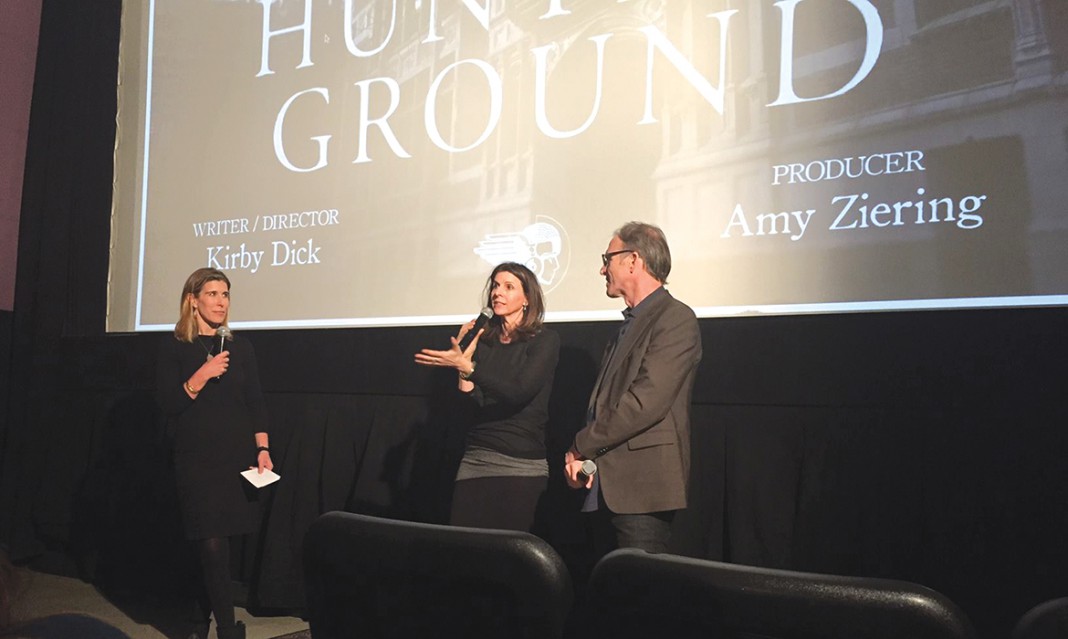

The feeling could have been inspired by any of the following: the premiere of HBO’s series Girls; American author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED talk, gloriously entitled We Should All Be Feminists; Beyoncé’s incorporation of the said talk into her music video “Flawless” and her 2014 VMA performance; Emma Watson’s UN speech in support of the HeforShe campaign; the brutal rape of New Delhi student Jyoti Singh and the subsequent country-wide protests for women’s rights; the Jian Ghomeshi fiasco; the Dalhousie dental school fiasco; or The Hunting Ground, a documentary about the prevalence and subsequent cover-ups of sexual assault cases on university campuses.

Things do seem different these days.

As far as I remember, five or six years ago there was little talk in our cultural sphere about sexual politics or the treatment and perception of women in the workforce, at school, and in the media. One heard little about that nuanced and complex term “work-motherhood balance”, or about why, in an age when women are roughly 60% of university graduates, the majority of the leadership roles in the world’s most powerful corporations are still filled by men.

Now such talk is everywhere. Sheryl Sandberg, the COO of Facebook, has delivered a series of TED talks focusing on the lack of female leaders in the top levels of the corporate world. Her holistic solution, that women must learn to “lean in”, has produced both a book and a social campaign. Marissa Mayer, the current CEO of Yahoo, has also been busy sharing similar words of wisdom. This has given shape to the uniquely 21st century idea of being told to pursue their goals with tenacity and fearlessness while on the other hand, that they can’t “have it all” or at least certainly not all at once. Women, it seems, are once more in the fray, but have they ever been out of it?

March 8 was International Women’s Day, and as a tribute to it I will be writing this series of articles talking about all things woman. Men, listen up too, because whatever involves half the world’s population inevitably involves you too. As the saying goes, we’re all in this together.

To begin with, let’s get to the root of the term. “It seems to me that the word ‘feminist’, and the idea of feminism itself, is […] limited by stereotypes,” Adichie said in her TED talk, and I concur.

Somehow the contemporary connotation is someone who hates men while trying to be macho, detests any sign of femininity, and believes that women should be superior to men. While it’s true that second- and third-wave feminism produced radical beliefs such as these, with a small minority of women choosing to live in female-only communes from which all males, including their own male children, are excluded, and where the very idea of sex is seen as oppressive, they are thankfully not shared by the majority of women. The truth of the matter is that women don’t dislike men; what we dislike is patriarchy. To quote Adichie again: “The late Kenyan Nobel peace laureate Wangari Maathai put it simply […] when she said, ‘The higher you go, the fewer women there are.’ ” We all have to ask ourselves why that is.

In her talk Adichie defined the term ‘feminist’ as “a person who believes in the social, political, and economic equality of the sexes”.

Emma Watson said it is “the belief that men and women should have equal rights and opportunities. It is the theory of political, economic, and social equality of the sexes.” She too noted that “fighting for women’s rights has too often become synonymous with man-hating”.

My very own Canadian Oxford Dictionary says feminism is “the advocacy of the equality of the sexes, especially through the establishment of the political, social, and economic rights of women”. Nowhere is there mention of man-hating or gender superiority.

By the end of the 19th century, first-wave feminism was well underway. Although at its core this was a suffragette movement, sexual and economic liberation was also under discussion. The mid-20th century saw the rise of second-wave feminism, which intended to further the gains of the first wave by, among other things, making the workforce more open to female employees, campaigning for equal pay, shared childcare duties, and laying claim to the sexual freedom enabled by contraception.

What I have been increasingly noticing is that third-wave feminism—which began in the 1990s as a campaign for abortion services and raising awareness of violence against women and the workplace “glass ceiling”—has been taking on a new shape in the 21st century and writing these articles is to define it.

The scars and division that was second and third wave are deep. The legislation that was enabled by them continue to do damage. The children that grew up in these times are exactly the ones most against not only the term but the movement. It was and is still quite disingenuous to assert it had anything to do with equality.