As outlined in Rosalind Krauss’s opening line to a chapter dedicated to Marcel Duchamp’s Etant Donnés in “Art since 1900,” a textbook she co-wrote with four other art historians, “One way […] of characterizing the aesthetic climate of the sixties is to notice the degree to which Picasso’s reputation had become eclipsed by Duchamp’s.” Indeed, although Picasso, Braque, Metzinger, Kandinsky, and other artists in the early twentieth century played with the standards of painting and laid the grounds for abstract expressionism, they were still following the rules of pictorialism.

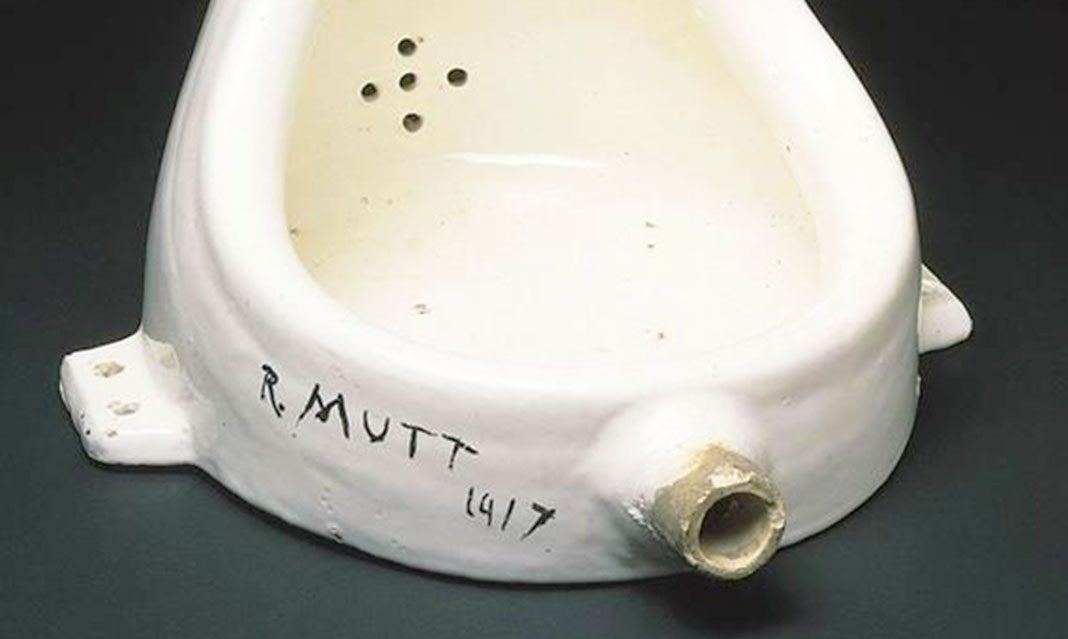

By drifting away from making art to choosing readymades—a term coined by Duchamp that refers to a prefabricated object of the artist’s choosing that is elevated to the status of art, and thus liberated from its original function—Duchamp became, and may still remain, a scapegoat to those who wonder why “real,” figurative art was replaced by impersonal geometric patterns, minimalistic metal cubes, theatrical performances with no plot or obvious meaning, identical repetitions of Campbell soup cans, and well, urinals.

What is the point of this work of art? Can I find a place for it in my living room to add to my artsy decor? Would my five-year-old son be able to replicate this work? As frustrating and ignorant as these questions might sound to most art lovers, these inquiries were the engine for a new generation of conceptual artists after Duchamp’s Fountain.

Before Duchamp’s readymade, art was compositional. There was a visual experience and retinal relationship between the viewer and the work of art. The existence of a composition both in painting and sculpture implied the existence of a maker—the artist—who was evaluated according to the standard’s composition and skill.

As early as in 1913-191414—before Picasso’s revolutionary Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was even presented to the public—Duchamp created, but did not yet display, his first readymades, Bicycle Wheel and Bottle Rack, challenging the idea of art as a planned composition for the first time. He took an existing industrial object and rid it of its function by misplacing it and sometimes combining it with other trivial mass produced objects.

Duchamp’s readymades were ordinary, and industrially produced to praise the everyday and the momentary—two concepts that fascinated Duchamp—to establish an intellectual rather than visual art-viewer interaction, to question the purpose of objects and of art itself, and to liberate the artist from crafting.

Up until Duchamp, the traditions of art required the artist to be the designer and craftsman of his work, who ideally would be recognizable from his “signature” subjects and technique. Duchamp removed the making and designing of art from this equation and moved the accepted relationship of the artist, their art, and the viewer of the art in an intellectual direction. Now, the artist’s main accomplishment was the idea: the artist became more of a thinker than a maker.

Thus, Duchamp removed the focus from the work of art and placed it on the immortality of the concept, which essentially would be what the artist would be remembered for. Duchamp didn’t see the point in authorship or signature style; anyone could copy his readymades without any training or skill, but those will only be replicas of the original thought. This shift in the artist’s role in the creation of art was one of the bases for the exploration of new purposes of art, especially in the works of Ellsworth Kelly, Carl Andre, Allan Kaprow, and Fluxus artists.

Marcel Duchamp is one controversial figure in modern art. He has been, and still is, praised by some and questioned by others, and an attempt to uncover the whole complexity of his motives and ideas would be desultory.

It would be appropriate to quote sculptor Carl Andre in this respect: “Art is what we do. Culture is what is done to us. A photograph of an art object is not the art object. An essay about an artist’s work is not the artist’s work.” However, regardless of the reading of Duchamp’s work and intentions, it comes without saying that his substantial contribution to conceptual art has served as the base for many artists to come after him, and is still present in contemporary art today.