Professor Alexandra Gillespie, a specialist in English and medieval studies in the Department of English and Drama, is co-leading a million-dollar initiative to develop tools that will aid the study and archiving of fragile and important items.

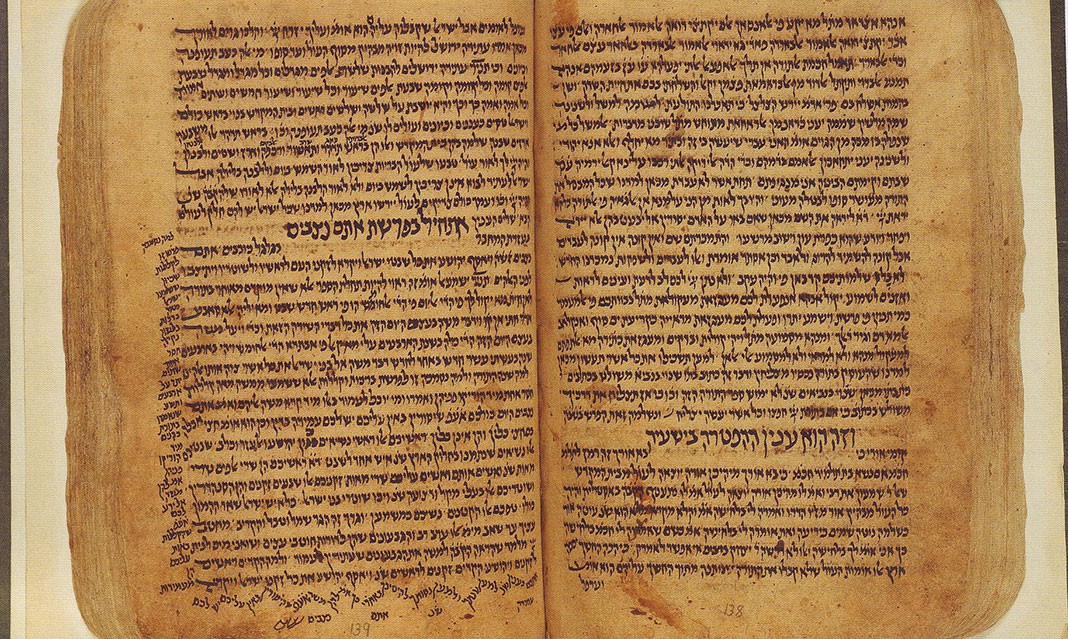

The project is specifically focused on medieval manuscripts and early printed books.

Aside from documents, items such as paintings, poetry, and archeological remains will also be included. In Gillespie’s words, the “project is about being able to sit in your bedroom in Mississauga and look at manuscripts in the Vatican, the British Library, the National Library of South Africa, and Harvard University”.

However, the project isn’t limited to simply increasing access to these medieval documents, but to also “pull them together into a space” where users can create their own exhibits or their own “narrative” about them.

The project will also “enable scholars to do in-depth scholarly work without having to travel to archives, able to do work when they’ve left and before they go and if they’re unable to go”. It would also enable them to “share results in a way that is interoperable so that other scholars can use these results”.

When asked about why the project is being coordinated now, Gillespie said, “We are [now] at a point where we are seeing a rapid increase in the number of objects that we are making available digitally, and the technology has developed enough that [we are] able to do different things. We’re able to make the objects available in ways that enable us to do more interesting things with them.”

Gillespie goes on to thank digital technology, which has given us a “whole new way of preserving these extraordinary things that have survived for thousands of years”, and through which we “are able to tell us amazing stories about the cultures they have come from”.

“We have a new way of accessing these objects, and we’re now 20 to 30 years into the Internet Age, and standards and methods of disseminating our information using technology have changed a lot,” she says.

Gillespie is co-leading this project with Sian Meikle, director of Information Technology Services at U of T’s Robarts library.

The ITS unit is responsible for “providing support for digital scholarship in all fields across the university,” she says. “It’s complemented from the support we receive here at the UTM library as well, but Robarts has a central role because it’s the core of the collection. [Robarts is] interested in finding new ways to support scholarship and pedagogy using digital tools and have some dedicated librarians doing that and the money came from the agency to work with the library to do this kind of development.”

Gillespie went on to say that “libraries, museums, and archives are the ones who are implementing the data models—that’s why the foundation that funds us, Mellon, wants to fund us to work with a library”.

This specific project falls under the overarching initiative of the International Image Interoperability Framework. Several libraries and museums are involved with this initiative.

Currently, IIIF is based on a data model known as Shared Canvas. The data model was at first used to share images of book pages. “Then they realized they could do this with paintings as well, and then they asked whether they could adapt the model to make it work for 3D images,” says Gillespie. “The images that are being shared are everything from oil paintings from the 18th century to medieval manuscripts and bits of archeological remains that were taken out of places like Syria and Iraq before the current civil war, and are now so important to preserving a cultural heritage.”

Other universities that are heavily involved with this initiative include the University of Pennsylvania and Stanford University. Gillespie stated that the latter university has played an important role in terms of driving IIIF through their technological development.

“We’re also working with the University of Pennsylvania [and] they have a slightly different approach to some of the same issues,” she says. “They are more interested in providing images that you can just download onto your desktop and work from there. One of the great things about this project is getting to have these international collaborations.”

When asked about the relevance of this project to those who may not be interested in medieval manuscripts, Gillespie stressed the importance of accessibility.

“For the general public, it’s about accessibility, and for everybody, it’s about sustainability. If we’re going to spend a lot of money putting all this stuff up online, we want it to still be there in 30 years,” she said.

As for the project’s relevance to students, Gillespie says that these “are incredibly important objects of study, and that’s true for any university student. There are all sorts of questions we can ask of this material, and they’re going to be questions that are interesting to students for all sorts of different reasons”.

She also challenged the question of the project’s relevance by asking what the Internet will look like in 30 years. “There’s a technological piece to the project that is of interest to anybody. […] Everybody is interested in these things. [For example,] the Star Wars trilogy is based on medieval romances,” she said.

In an appeal to current global issues, Gillespie added, “If we’re talking about places like Syria and Iraq [and] some of the sites that are being destroyed—sometimes archaeologists will say that history and art are the glue that holds the community together, and so we think about what will happen after the war—we need heritage [and] the past.”

Gillespie also referred to the potential of the creation of a video game in the future, which will use real medieval transcripts instead of pretend ones. “That’s a UTM sub-project, [and] I’m working on this project exclusively with UTM students.”

“When you bring together really wonderful scholarship in the humanities, with fantastic scholarship in technology and data science, really exciting things happen,” she said.