Jurassic World enthusiasts may be shocked to hear that a Canadian dinosaur fossil, originally discovered by a farmer in the 19th century, had been misidentified and wrongly proclaimed for over a century. Researchers, including two UTM palaeontologists, have correctly identified the previously-named Bathygnathus borealis to actually be the first Canadian Dimetrodon fossil.

The farmer had discovered the dinosaur fossil while digging a well in the French River district of Prince Edward Island in 1845. Due to a lack of natural history museums in Canada at the time, the farmer sold the fossil to the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, U.S.

Joseph Leidy, a prominent palaeontologist at that time, believed that the fossil was the lower jaw of a dinosaur, and mistakenly identified it as a Bathygnathus borealis fossil in 1853. Bathygnathus refers to the fact that the dinosaur has a “deep” jaw, while borealis indicates its northern origins.

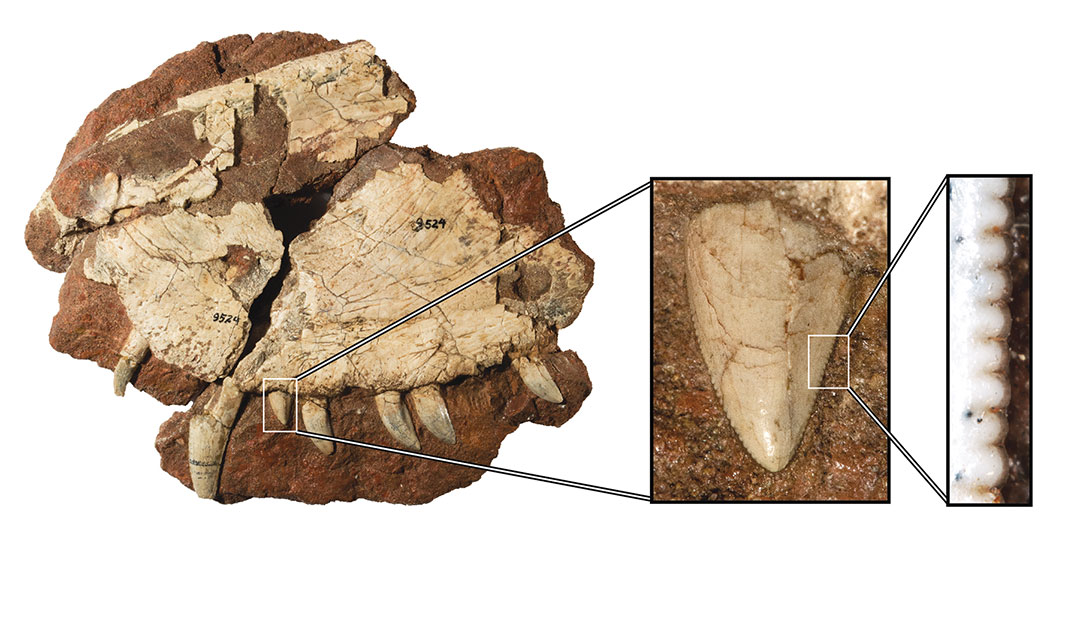

“Bathygnathus borealis is an extinct animal known from only one fossil, a jaw with teeth,” comments Dr. Kirstin Brink, a palaeontology graduate alumna at UTM.

“It wasn’t until 1905 that the [fossil discovered on Prince Edward Island] was recognized by palaeontologists as the upper jaw (maxilla) of a sphenacodontid, which is a group consisting of the ancestors of mammals, not dinosaurs,” says Brink. “The most well-known sphenacodontid is Dimetrodon, whose most recognizable feature is an elongate dorsal sail […] Dimetrodon is often mistaken for a dinosaur, but is more closely related to mammals (and therefore humans) than it is to dinosaurs.”

Despite palaeontologists recognizing that there were inconsistencies in the so-called Bathygnathus fossil, the identity of this particular Canadian fossil was not clarified until 2015.

While completing her Ph.D. studies at UTM, Brink’s research focused on specifics of dinosaur anatomy, with a significant emphasis on tooth structure. Alongside her supervisor, Dr. Robert Reisz from the Department of Biology, she studied the evolution of Dimetrodon teeth across 25 million years, leading to conclusions such as the fact that a serrated tooth structure (as seen in the Tyrannosaurus Rex) allowed top predators to rip flesh effectively from prey. Their research has been published in science journals such as Nature Communications and Scientific Reports.

During her research, Brink came across the Bathygnathus fossil and believed that she may be able to correctly determine its identity based on its teeth. She and a team of researchers (Reisz, Hillary Maddin from Carleton University, and David Evans from the Royal Ontario Museum) attempted to put an end to the questions regarding the fossil’s identity.

The fossil was transported from Philadelphia to Toronto, where CT scans were performed at the Princess Margaret Hospital to observe the internal anatomy of the fossil. The images were then processed at Carleton University. This led the researchers to realise that the fossil, according to Brink, had “teeth [that were] blade-like with tiny serrations along the front and back of the teeth”. This tooth structure was similar to that of a Dimetrodon.

However, the fossil had an unusual facial structure where the septomaxilla bone was greatly exposed. This was an observation that had not been recorded in previous Dimetrodon fossils.

So was the fossil a Dimetrodon, or had it been correctly named as Bathygnathus borealis for the last century?

To answer this question, the researchers then constructed a family tree for both the Dimetrodon and the Bathygnathus families to compare their evolutionary histories. The team realised that the Bathygnathus borealis was the sister of the Dimetrodon grandis, and that this Prince Edward Island fossil must be a new species of Dimetrodon.

“Based on the study of the anatomy of the teeth of Bathygnathus and the results of the new family tree, Bathygnathus borealis will be renamed Dimetrodon borealis,” says Brink. “This marks the first occurrence of a Dimetrodon fossil in Canada. Dimetrodon is now known [to occur in] the U.S., Canada, and Germany.”

The team’s discovery, “Re-evaluation of the historic Canadian fossil Bathygnathus borealis from the Early Permian of Prince Edward Island”, was published in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences in November 2015.