Oftentimes our history books are written by those with the power to tell it. These narratives are therefore subject to distortion and in certain cases, leaving certain characters and perspectives excluded from public rhetoric. Curated by cheyanne turions and located in the Art Museum at U of T, I continue to shape exhibits a collection of artworks that aims to resist dominant discourse on colonialism and recontextualize the Indigenous experience. The artists prove that when given the agency to challenge long institutionalized patterns, they have the power to transform a one-sided history and to generate new narratives via the art they create.

Nicholas Galanin’s photographic composition “Things are Looking Native, Native’s Looking Whiter” is displayed by the entranceway of the exhibit. He juxtaposes a photograph of Princess Leia from the Star Wars franchise with a photograph of a Native woman side by side. The parallels in their appearances are striking. Both women wear high-necked robes and don stoic facial expressions. Most notably, both women have their hair parted down the middle and tightly coiled in side buns. Galanin illustrates not only the obvious influence of Indigenous culture on the iconic hairstyle of Carrie Fisher’s character, whether deliberate or unintentional, but also the cultural appropriation that occurs in media, and more specifically in films of the science fiction genre.

Etymologically, the word “utopia” directly translates from Latin to “no place.” Maria Thereza Alves’ photographic series titled “Nowhere” delineates European ideas of utopia and their effects on Indigenous life and lands around the world. Alves’ photographs depict areas of Brazil, where she is originally from. Using black sharpie markers, she has physically edited each photograph, disturbing the portrayals of the natural landscape. There is one photo that is almost completely covered with sharpie markings, suggesting the erasure of Native imagery by colonial settlement. Alves hopes to shed light on how people in South America were objectified by colonizers who thought their land was a blank slate to start anew. Between her photographs on the wall are long wooden beams, similar to those found in construction sites. They represent the deconstruction of predominant ideas of colonialism and the reconstruction of more holistic ones.

In a series of paintings titled “Props for Reconciliation,” Joseph Tisiga incorporates characters from the Archie comic books with representational tropes from Indigenous cultures. In one painting, Jughead seems to be dismissing a ceremonial pipe being offered by a Native chief. Indigenous iconography such as a tipi in the background suggests that they are on Native lands. The surface of the painting is abrasive and faded, perhaps to indicate how Indigenous culture is fading from the forefront of its own story.

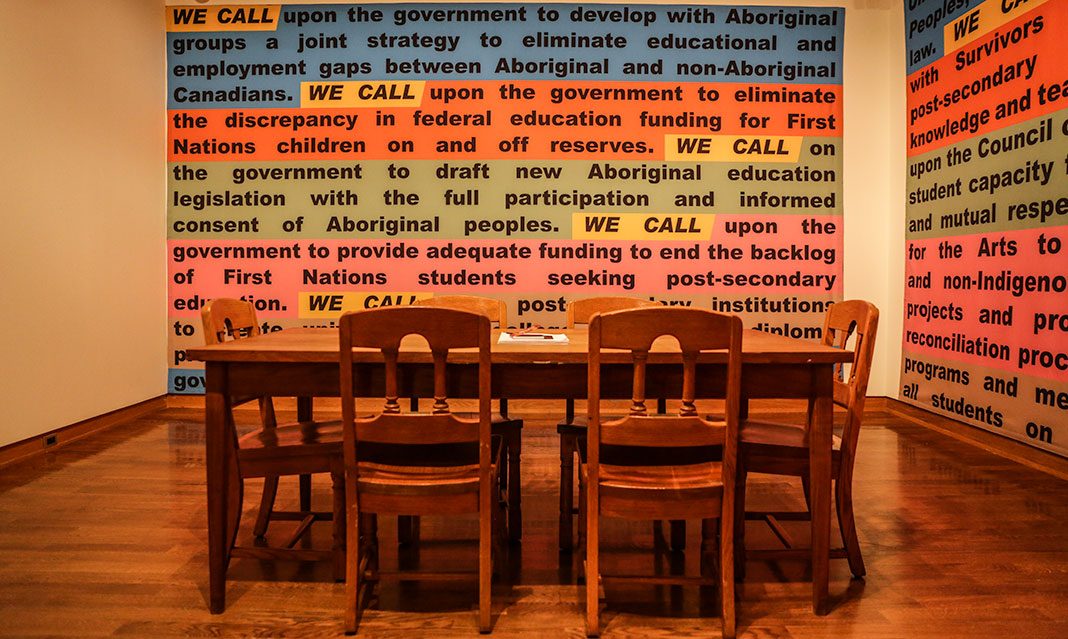

“WE CALL,” a two-wall text painting by Cathy Busby, is a vibrant installation portraying calls to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report. Each phrase begins with a capitalized and highlighted “we call,” and is followed by a request addressed to academic and cultural institutions. One call read, “WE CALL upon post-secondary institutions to create university and college degree and diploma programs in Aboriginal language.” These wall-text panels loudly remind us of our role in dismantling the structures we have inherited and shaping a world more tender and more just than the world we have now.

I continue to shape runs at Art Museum at the University of Toronto until December 8.