Before Derek Jarman became a feature film director, he was a stage designer. Before that, he shot his own experimental short films on Super 8. His art background shines in his feature film debut: the 1976 release Sebastiane (co-directed by Paul Humfress).

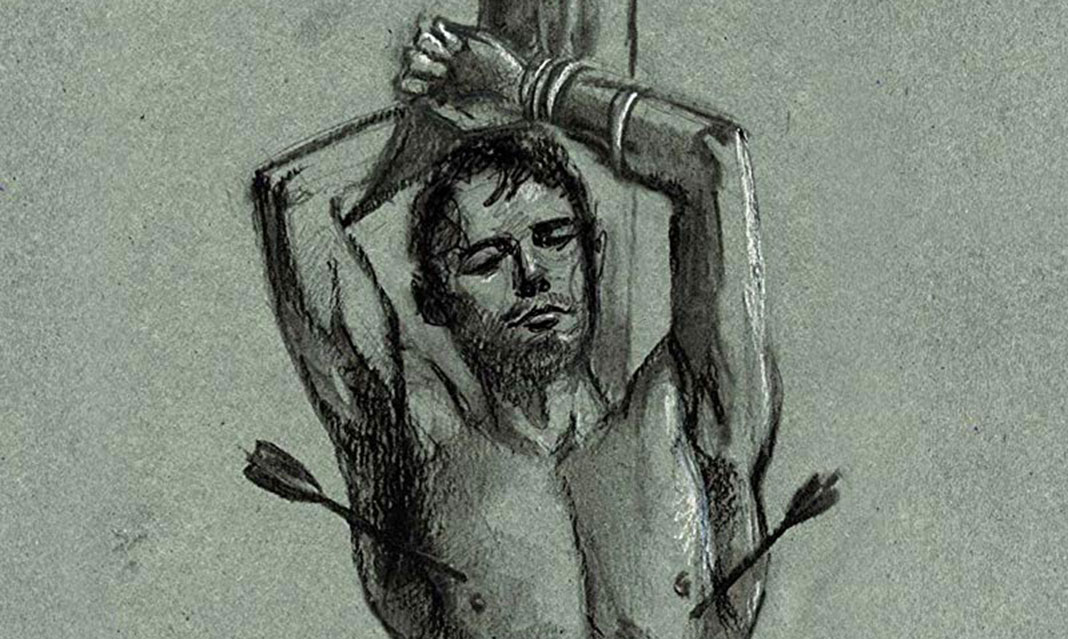

The film follows Christian martyr Saint Sebastian, a member of the Roman Emperor Diocletian’s guard. Demoted, he is cast away to a desolate coastal base where other men who have been cast out have resorted to homosexual activities. He rejects the advances of the obsessive Severus, a superior officer, which leads to Sebastiane’s torture and ultimate (and iconic) execution by arrows.

To be frank, when I watched this movie, I was coming off the high of Jarman’s later 1986 release, Caravaggio, a film that presents the artist’s life in stage-like sets and loose Caravaggio-esque tableaux. It was the film debut of Tilda Swinton and Sean Bean. It featured a young Mick Jagger-doppelganger Dexter Fletcher as the eponymous subject of the painting “Boy with a Basket of Fruit” (1593).

I didn’t expect the homoeroticism in Sebastiane to be most, if not the point, of the film. That’s what I get for not reading synopsis or reviews beforehand.

While I wasn’t entirely swept up with Sebastiane as with the director’s other arthouse “biopic,” I was still deeply affected, largely by the film’s sensuous nature. True, most of the film does include romping male bodies, but beyond the lust that Jarman headily portrays are the arresting textures of the film. My sense of touch was especially engaged in every scene: I could feel the heat of the high Roman sun on my own nape, the coarseness of the beach sand between my toes, and the relief of cool water on my skin in one particular slow-motion sequence.

It is a fleshy film, both within the frame, with all these bodies presented starkly as bodies in unbridled abandon, but also without the frame, with the haptic reactions it elicits in a viewer through the variety of textures. The cinematography allows for this tactile identification of a viewer into the film world’s desolate coastal landscapes.

The film is obvious in showcasing the talent of a budding but still developing filmmaker. There are aspects of Sebastiane that fights with a viewer’s suspension of disbelief. For one, the flimsy costumes of the Roman men looked like haphazard ensembles. The weapons looked fake, some even bending during fight sequences. However, Jarman made do with the tight budget—this film would not be the last of his funding problems, which he battled throughout his entire career as an artist. The use of Latin, the only spoken language in the movie, was also a stretch at times. Lines were delivered with awkward cadence and undistinguishable accents, but the minimal dialogue isn’t the point of the movie. It could have gone without it and the film would still be visually arresting, perhaps even more so if it solely rested on the shoulders of the eerie, winding score penned by music legend Brian Eno.

At its face, Sebastiane seems like a gratuitously homoerotic piece of 1970’s “avant-garde” work. In retrospect, the film shifts into a reverent space, considering Derek Jarman’s activist work for LGBTQ+ causes during the 1980’s. Sebastiane was an indulgent, controversial, and incendiary film, an important feature film release in late 1970’s England. While the film didn’t quite break Jarman into the arthouse scene, it did set up a foundation upon which his deserved place in the experimental Queer Cinema canon could stand comfortably.