The case of Alan Strang is a strange one. His crime seems unspeakable, his motives an enigma. Yet his sentence is the same as those of countless others: to be evaluated, treated, and cured by modern psychology. But what is it that brings this teenage boy to brutally blind six horses at the stable where he works? Equus, the groundbreaking play by Peter Shaffer, offers not only an answer to this question, but offers a jarring and thought-provoking journey into the passions and the psyche of a disturbed young man as well as the psychiatrist who attempts to cure him.

Under the direction of Elenna Mosoff, Equus premiered last Friday night at Hart House, telling the jarring and controversial story of a young boy’s sexual awakening, psychological demons, and above all, his intense passion.

“Afterwards, he says, they always embrace. The animal digs his sweaty brow into his cheek and they stand in the dark for an hour like a necking couple…” Martin Dysart, a child psychiatrist, sits alone in darkness. When the lights come back on, court magistrate Hesther Salomon tells the doctor, “I’ve just come from the most shocking case l ever tried…”

Alan Strang ends up in Dysart’s office, and thus begins his treatment with the famed child psychiatrist.

What ensues is a look into the twisted, passion-filled world of a boy with a strange sexual and religious fascination with horses, and the aging psychiatrist who attempts to help him while wrestling with his own feelings of dissatisfaction in life.

From the very first words he utters, Peter Higginson gives a commanding performance; his calm, composed portrayal of the aging and disillusioned psychiatrist Martin Dysart, offers a perfect opposition to the frantic outbursts of Jesse Nerenberg as the disturbed Alan Strang. Nerenberg himself seems to bear it all on the stage, literally and metaphorically. His explosiveness and vulnerability is palpable; the entire stage is alive with his frenzy. Although at times his outbursts seem exaggerated, they are undoubtedly what the part calls for, as the disturbed mind of Alan Strang is surely a place of equal explosiveness. Thomas Gough, as the boy’s father, Frank Strang, delivers an impeccably natural performance, reflecting the stern attitude and worries of many a father against his son. Claire Acott plays Alan’s mother, and she echoes her son’s emotion with her own kind of worried frenzy. Although her performance seems contrived at times, it is perhaps necessary to match the intensity of Nerenberg’sperformance.

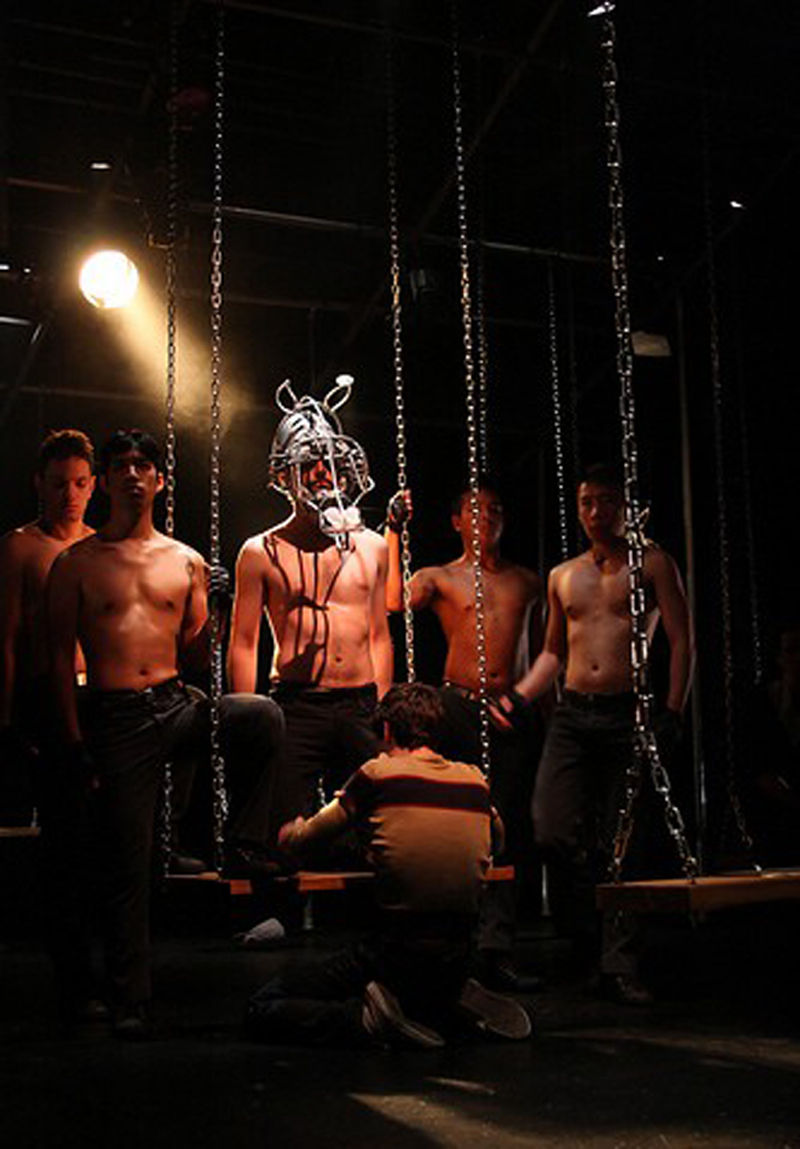

Even before the play starts, the element that draws the most attention is undoubtedly the set design.

Row upon row of metal-chained swings fill the stage; at first glance, without any actors on the stage, the set looks like something out of a shady club. Metallic wire horse heads hang in the background, and the entire scene sets the tone perfectly for the overarching theme of sexuality and sexual perversion. During the entire play, all the actors sit in the background on swings, watching the action unfold. Behind them, five shirtless men stand silently with the wire horse heads over their faces, playing the part of horses and mirroring the boy’s own disturbed psyche. They are constant reminders of Alan’s obsession, and this fixation is ultimately mirrored onto the audience as well. The strong sexual overtones are relentlessly conveyed throughout the piece, and though this might prove to be too much for some audience members, it reflects the vital themes of the play with intensity and force. However, the metallic swings seem to both add and subtract from the performance; they serve as constant reminders of the chains and constrictions of our own society. The avant-garde style offers a new kind of space within which the actors move, as its openness enables the audience to see every bit of action going on. However, the metal swings are somewhat of a distraction at times, as they draw the attention away from the plot. The lighting and sound are perfect compliments to the frenzied performance of Jesse Nerenberg; strobe lights seem to mirror the frantic state of his mind. Piercing sounds and heavy breathing of horses and clacking hooves seem to offer a perfect soundtrack to the vital scenes of the play.

Equus offers a look into the impassioned mind of a disturbed young man, and the constricting world of normalcy in which he lives—and, ultimately, in which we all live. The avant-garde set design and commanding performances of Nerenberg, Higginson, and others, seem to be a mirror of our own society, of our own unrelenting need for normalcy, and what we ourselves do to those individuals with too much passion to exist in our world of psychological chains.

Equus runs from November 12 to 27 at Hart House Theatre; for details, visit the Hart House Theatre website at harthouse.utoronto.ca/arts.

Mature content warning: Equus contains full-frontal nudity, coarse language, and adult situations.