Disclaimer: for the sake of the experience, I will do my best not to spoil anything.

Undertale is an indie video game developed by music producer Toby Fox with art contributions from Temmie Chang. You play a human child who falls down through a cave into the Ruins—a small portion of the Underground where monsters have been banished after a decisive war. By exploring your surroundings and talking to characters throughout the game, you are exposed to the history of the war and the struggles of the monsters. Warning: it’s sad.

The game switches between an adventure/puzzle-solver, an RPG, and an arcade bullet-hell. To some this may sound like a disorganized mess of genres, but Undertale blends them seamlessly into fluid gameplay. You travel through the Underground, solving puzzles and interacting with characters and objects (sometimes both at once). Once you enter a “battle”, you switch to an RPG-style screen, with options to fight, act, use an item, or show mercy (spare). After each turn, you will face an attack that you must play through in order to take another turn. In those instances, you control a red heart sprite, which is described as your SOUL—the very culmination of your being. Attacks vary from dodging dogs and jumping through a scrolling platformer to standing absolutely still.

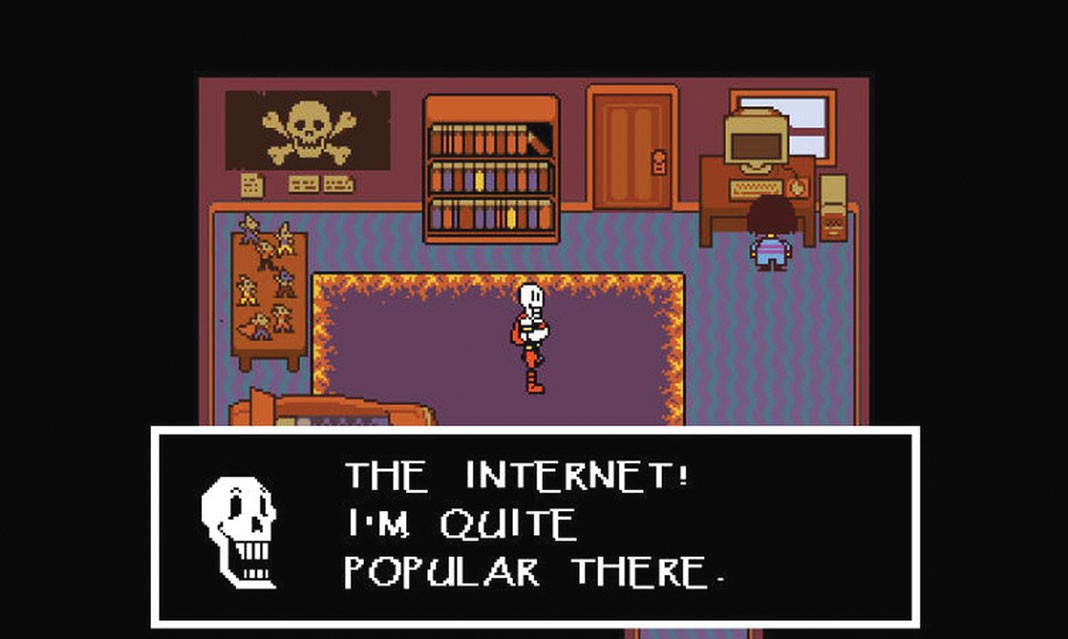

As far as graphics go, you’ll immediately notice that Undertale—like many other indie games—takes the retro approach. However, the art style varies throughout the game. Some sprites will look like they were programmed for the Atari, and others will have pixel shading so creepy you’ll think you’re in Amnesia. One shop background in particular looks like it had a lot more work put into it than the rest. And you’d think these kinds of inconsistencies would make the game look unfocused, but it only adds to the charm. Being able to laugh at a goofy cat drawing and simultaneously be in awe of a distant castle gives the game a wide range of emotional variety.

Undertale is unique in that you can technically beat the game without fighting anyone at all. The “battle” system is more of an interaction system. You can fight and kill monsters, but you can also act—perform different actions towards different monsters until you are able to spare them. In the game’s canon, monsters are weaker than humans in several ways. They are essentially at your mercy. The game’s ability to teach empathy also stems from this idea. If you choose to go through the game killing, monsters will act vastly differently towards you than if you do a pacifist run. The story and the ending also change dramatically.

The only problems I have with Undertale are its length and its lack of diversity in the puzzles. The game compensates for its length by having multiple endings. To its credit, it does try to make the experience different each time. The genocide run is still a huge grind though. And the puzzles you’ll encounter are not a challenge at all. The game makes up for it by having challenging boss monsters, but that’s not a substitute for people looking to solve more puzzles.

Regardless, Undertale is still one of my favourite games. For every interaction, you can expect a funny, unusual, or just plain silly reaction. Every character, no matter how minor, is full of personality.

At one point I found myself feeling bad for a snowman, so I vowed to take a piece of him to the end of the game with me.

Welcome to Undertale.