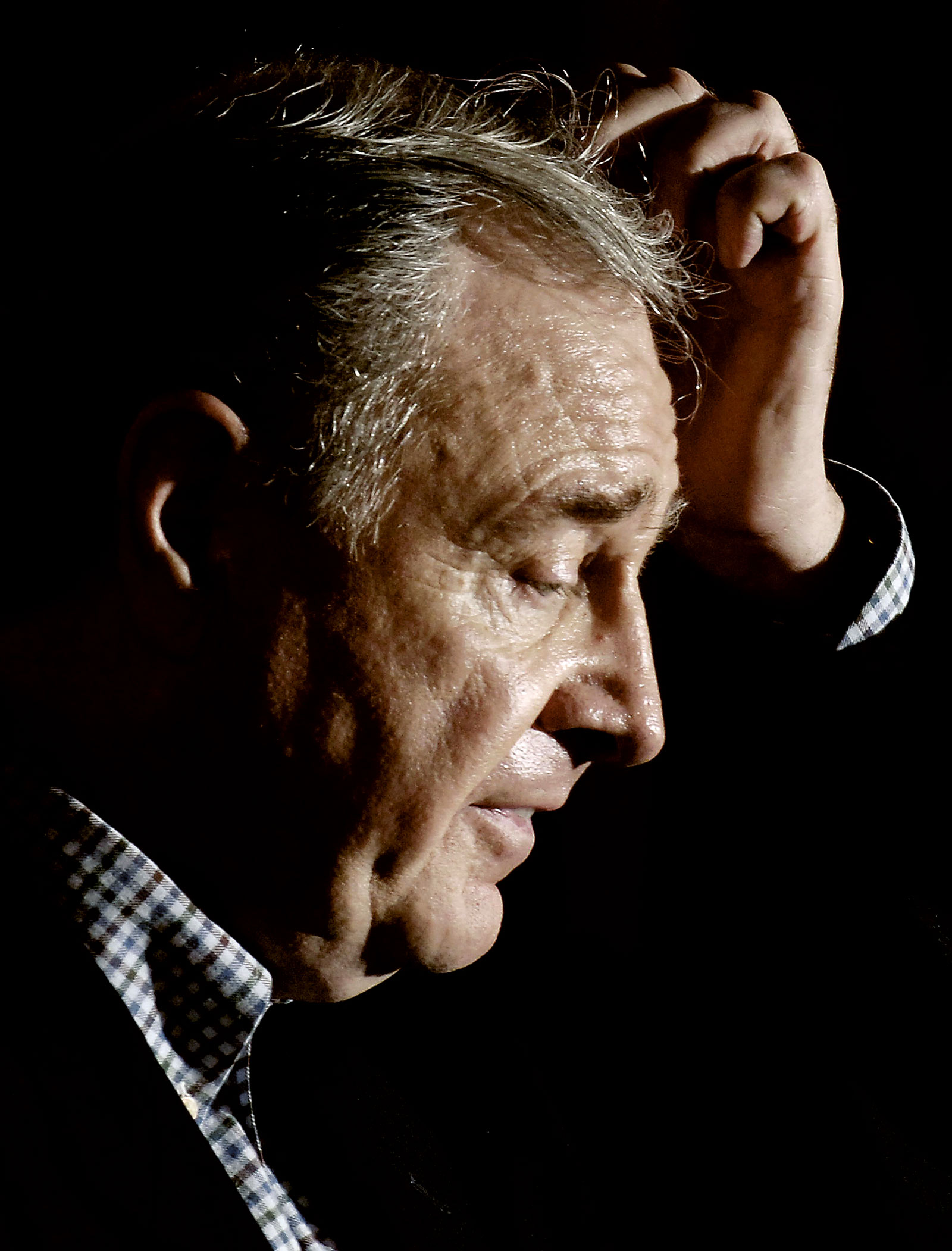

Paul Martin was prime minister for just over two years, but his interests while in office were diverse. In retirement, he has continued to pursue issues ranging from the state of the environment to global poverty and inequality to Aboriginal education. He also attended U of T during one of the most exciting and dynamic periods in its history—a time as formative for him as it was for Canada.

Paul Martin was prime minister for just over two years, but his interests while in office were diverse. In retirement, he has continued to pursue issues ranging from the state of the environment to global poverty and inequality to Aboriginal education. He also attended U of T during one of the most exciting and dynamic periods in its history—a time as formative for him as it was for Canada.

I wanted to begin by asking you a bit about your own time as a U of T student. I saw that you went to St Michael’s college for your undergraduate and studied philosophy and history. And both your parents went to U of T—were they also St. Mike’s students?

No. My mother was in pharmacy and then she was also at the Conservatory of Music. And my father went to St. Mike’s.

And what did he study?

Philosophy.

So your family has some roots there. Did anyone else in your family go to U of T?

Sure—I can do one better than that! My wife went to UC, her parents went to UC, and two of my three sons went to St. Mike’s.

What was your own student experience like? I guess you would have graduated in the early 1960s.

I graduated in 1961 from St. Mike’s; in 1964 from [U of T] law school.

What can you tell me about your life as a student? What kinds of things did you involve yourself in?

Well, at that time—I don’t know what it’s like today—they had a very active intramural sports program. So I played football, basketball and water polo for St. Mike’s. I would like to say that my time at the University of Toronto was spent completely in the library, but I suspect that would be a bit of an exaggeration. One thing I would say—and I don’t know the degree to which you’ve been able to keep it based on what you told me [before the interview]—but I’ve always thought that one of the great advantages of the University of Toronto was the university system within the university. In other words, you had all the benefits of going to a smaller school like St. Mike’s and yet all the benefits of going to a great university like the University of Toronto. My time at St. Mike’s: it’s one of the great schools of philosophy in the world, as an example. […] The English department was particularly strong. Marshall McLuhan was there and taught in the same house I used to live in. I probably spent more time auditing his classes than the ones I was supposed to go to.

Is it true that he used to give lectures lying on his back on a sort of Roman emperor’s chair, or is that just a rumour?

I heard that! I never saw it. I was in house number two at St. Mike’s. Our rooms were in the front, but in the back there were professors’ offices, and he used to give his classes in his office. I used to just go in, sit at the back, and listen. He was terrific.

So he wasn’t impossible to understand?

Oh, he was exactly as advertised. He was a very good communicator. But the great advantage is that you’ve got all the great advantages of a smaller university like St. Mike’s, where you got to know the professors, and then at the same time you took other courses across campus. For instance, history, I took them over in the history building, and the tutors that I had were some of Canada’s greatest historians; and so, in my time, I think the University of Toronto, as it is today, was one of the great universities in the world.

Were you involved in politics at all when you were here, or was that something that came later?

I was not. I was a member of the university Liberal Club and I went to the model parliament, but on my list of priorities politics was not very high. I think sports was really my main priority. My father was in [Lester Pearson’s] cabinet when I was in university so naturally the Liberal Club came and got me! But no, I had very little interest in politics at that time.

When did that develop? Did it develop in your graduate studies or not until later?

It really developed much later. You’ve got to remember, I grew up in a political household, so I knew it pretty well. My main interests were elsewhere. For instance I marched in the civil rights marches in the United States because I grew up in Windsor, right across from Detroit. I had obviously been heavily influenced by people like Martin Luther King Jr. My other interest was to go to the third world. My intention was to get my law degree and go to the third world, and that’s really where my ambition lay.

Do you think your experience as a student shaped your later life and career in any major way?

Without a doubt. The great advantage of going to U of T was being exposed to some of the great minds. It was a world opening up. I spent most of my summers working in the north, in the Arctic, and then I would come back to school [after] the stillness of the Arctic and the Beaufort Sea or the Mackenzie River. I would then come in and sit down with people like Tom Symons, who later went on to be the President of Trent, or CP Stacy, who was the Canadian Army’s official historian. To have exposure to people like that or Marshall McLuhan, or some of the great medieval scholars at St. Mike’s—it was just impossible not to be influenced by them.

I suppose your own generation was a bit more activist in orientation than my own, though one possible exception is the recent Occupy movement. And you, I think, surprised a lot of people by saying, “These young people have touched a chord that is being felt in every family across North America and in Europe. I think it’s very important what they’ve done.” Could you comment on those remarks? What did you mean by that?

Exactly what I said. The fact is that inequality is unfortunately part and parcel of every economic system. It could be socialism, free market, or state capitalism, whatever you want. Inevitably, a group of elites essentially begin to accumulate more and more of the wealth, and the poor get poorer and poorer. The essential success of free market capitalism has been its marriage with liberal democracy and its marriage with the redistribution of wealth. The only way to deal with savage inequality is to recognize the absolute necessity of redistributing wealth, through your healthcare system, through your education system, through social programs that will enable people who are not born to wealth or privilege to accomplish their own goals and to rise up on the income scale. Its greatest manifestation, in my opinion, was in the postwar years of the ’50s and the ’60s.

To give you an example, when the United States and the Brits were weakening banking regulation in order to attract financial institutions [in the 1990s], I fought it strongly because I said that free market capitalism without strong regulation on the one hand and the redistribution of wealth on the other will lead to massive inequality—and massive inequality will lead to a society which simply will not work. It will also lead to a society that’s immoral, in my opinion. Immorality lies in the accumulation of massive wealth by a tiny, tiny percentage when the majority are poor.

So I think what the Occupy movement did was important despite people accusing them of not having clear goals. The fact is that Canadians are essentially decent, and the Occupy Movement crystallized what I think the vast majority of people felt.

If I can make a digression based on something you said, what do you make of the current debates in the United States surrounding all of this? Everyone’s been following these Republican primaries very closely, and lots of people watched President Obama’s State of the Union address. It seems like there’s quite a substantial polarization across the world, but especially in the United States, on these issues. What’s your impression of particularly what’s going on in the United States surrounding this debate?

I think that fundamentally, it’s the result of fear. I don’t have much sympathy for the Tea Party but I think that what you’re seeing there is the result of fear.

Fear of what exactly?

The reason that we’re seeing these inequalities right now is not only a failure in the United States of having adequate redistribution of wealth—and remember, I’m not talking about confiscatory redistribution. I’m talking about education, healthcare, early learning for children, and money being spent on diseases and on the poor. What’s happening, clearly, with the rise of Asia and the rise of the newer technologies is that so much that was done by unskilled labour in my time in the US is now being done by unskilled labour in Asia. So many jobs are being changed fundamentally by the newer technology that requires a lot more education to handle. And that has caused huge fear in the United States.

I was reading a passage from your book last night; you observed that there’s a lot less job security now than there was when you graduated, because of many of the things you’ve just described: the changes in the global economy and the demand for many different kinds of skills, etc. How good do you think our education system in Canada is at dealing with the rapidly changing nature of the global economy and equipping students for the futures that they hope to have?

I think that our education system, at the university level, is very good. To the extent that there may be more technical skills required, I think they are being provided by our college system. A lot of young people are going from university to college and from college to university, so you’re starting to get a proper blend of those things. I think that the real problem lies in our grade school and our high school system. The fact is that when people graduate from high school and they can’t really read or write, when they don’t have an accurate handling on math, I think that that’s where the failure lies.

Is that an issue of funding? Or is it something else?

In the case of Aboriginal Canada, where I’m now spending most of my time, it is absolutely a question of funding. I’m not quite sure where the problem lies in the grade schools and the high schools outside the Aboriginal system, but I certainly see the results. I’ve talked to too many people your own age and asked them the question, “How ready were you for university? Were you challenged in grade school or high school?” and most of the young people I’ve talked to would share the views I’ve just expressed.

The U of T and other universities now seem to serve a dual purpose. They’re both there to equip people for specific careers in engineering, medicine, etc., but also to be places that create better citizens, and teach people history and philosophy… The role there is less about equipping people for jobs as such, because it seems there are fewer jobs available in those fields. So what do you think about that?

Let me go back for a second. I’m incredibly proud of having graduating from the University of Toronto. I’m very proud of St. Mike’s. I brag about it around the world… I think that compared to many other universities around the world it’s really at the forefront, and I don’t say that just because I’m talking to you!

You see that the university system in parts of the US and Europe is in real trouble. Compared to U of T it’s night and day, all of it in favour of U of T. I think that the students that are going to U of T can have real confidence in what they’re getting compared to what would be offered to them in many other universities around the world.

But let me turn to [what you said]. Not that long after I graduated from law school and got into business [at] the end of the ’70s, which was a low point in the economy, I gave a lecture at the law school. In fact, it was in David Johnston’s class, the current Governor-General. One of the students stood up and said to me, “Mr. Martin, you have said that when you graduated from law school it was your intention to go to the third world, and I notice that you were very actively involved in the civil rights movement in the US. Why weren’t you worried about getting a job? To which my response was, “I was a pre-baby boomer and I never had to worry about getting into law school. But the fact is that there’s a problem with your generation. Mine wanted to go off and help, and based on what you’ve just told me, you don’t want to do that!” And then he said to me—and I’ve never forgotten this—“Don’t you understand? You just told us that you didn’t have to worry about getting into law school and didn’t have to worry about getting a job when you graduated. One third of this class doesn’t know if they’ll ever get a job as a lawyer, because that’s the current state of the economy, and you had the luxury of spending a lot of your time doing things that did not lead to a job because that was the society and the economy in which you grew up.” And I have to say, that was a lesson for me.

So you agree that the kind of reality students face today is quite a bit different. What advice would you give them, if any?

Well, it would certainly be that if education was important in my time, it is even more important today—in ways that we’re only beginning to understand. What has happened now is that labour is available globally, and it is those countries [that] are able to focus on a constant creation of value in terms of the economy [that] are going to survive, and that creation of value is going to come from education. The people who are going to take advantage of it are going to be educated.

I’d like to ask you a bit about what you’re up to these days. We spoke a few moments ago about your involvement in First Nations issues and Aboriginal education in particular. Recently, these things have been very much on the national agenda following the emergency in Attawapiskat. In an interview you did in January, you said that the First Nations issue was the “single most important social issue we have as a country”. How have these issues come to be so important to you?

I basically spend my time on three areas. One of them is the G20; I was one of its main initiators and the first chair of the G20 as Finance Minister. I really believe that for a country like Canada, the G20, which is developing into a global steering committee in order to make globalization work, is very important – the issue is how do you make globalization work not simply for the West or not simply for the East but how do you make it work for everyone? This is the crucial international issue of our time, whether it’s the Arab Spring, whether it’s Africa, or whether it’s just making sure there are jobs in Windsor, Ontario.

The second issue I work on is Africa. I’m involved in two big projects, so that’s where I spend a lot of my time. As prime minister and as finance minister I spent a lot of time on Africa because it is the area of the greatest concentration of poverty in the world.

And that provides a little bit of an introduction to the Aboriginal issue. You will see, when you’re in Africa, there are a lot of young Canadians working there. I have never been to a poor African village that was as bad as some of the poverty that I have seen on reserves in northern Canada. You have to ask yourself: why aren’t there young Canadians working up there as well?

And that is really one of the major issues that we as a country must face. In a rich country like Canada, the youngest and fastest-growing and most vulnerable segment of our society are Aboriginal Canadians—many of whom are living in poverty the likes of which you don’t see anywhere else. That is a moral issue, and there is no greater in this country, in my opinion. And it is a direct result of attitudes born of colonization which have lasted until very recently; for instance the last residential school was closed in 1993. It is, in my opinion, not only the most important social issue in the country, but when you think that this is the youngest and fastest growing segment of [the] population, it is also the most important economic issue and it’s the reason as prime minister I brought in the Kelowna Accord—which, unfortunately, the current government did not honour. But the motivation behind it is as important today as it’s ever been.

You’re involved in two initiatives: the Capital for Aboriginal Prosperity Entrepreneurship Fund, and the other is one you founded five or six years ago, the Martin Aboriginal Education Initiative. What can you tell me about these?

My son David and I started CAPE. If you’re an Aboriginal Canadian or a group of Aboriginal Canadians and you want to start a business, it is virtually impossible for you to get mentorship—in other words, to learn business. I ran a shipping company because someone taught me how to run a shipping company. I was mentored. And it’s almost impossible for young Aboriginals to get mentored and to borrow money. So we set up this investment fund to do the two: to say that if you want to start a business and you’ve got a good idea, then let’s get together with some people who understand that aspect of business and we’ll help fund it and sooner or later you’ll be able to buy us out and take it on.

On the education side, Canada’s universities have played a phenomenal catch-up in efforts to bring young Aboriginal Canadians into universities. Unfortunately, the same thing does not exist in early learning, primary school or secondary school. On reserve education is underfunded by a factor of between 20 and 30%, which means you don’t have labs, there is a shortage of qualified teachers, and consequently when you graduate from school you’re way behind, and that’s why there is such a high dropout rate. If you’re graduating from grade school and you want to go a high school off-reserve, and you’re two or three years behind, it’s not long before you’ll drop out. So what I’ve done is to say that elementary and high school is where the improvements have to take place, and that’s where we’re going to focus.

Aside from the issues you’ve discussed, there are a lot of political issues associated with this—and you brought up the Kelowna Accord. What are the problems that are preventing a greater harmony between First Nations leadership and the federal and provincial governments? What do you think needs to be done there?

First of all, I think the provincial governments are way ahead of the federal government. I think there’s a real understanding about what has to be done. Part of the reason for that is that the provincial governments live with the issue; 15% of downtown Winnipeg, Regina, [and] Saskatoon are Aboriginal. I think Edmonton has the largest Aboriginal population of any city in the country apart from Toronto. So they live with the issue and they understand where the solutions lie. For far too long, federal governments of all political stripes have actually had as their goal assimilation. And the Aboriginal leaderships have said quite properly “No way.” The ability to maintain culture and identity is an essential part of what [they] need to succeed, and the Federal government has never really understood that.

For this reason Kelowna was a most important event. It’s where for the first time in the history of this country, the prime minister of this country, the premiers, the territory leaders, and the Aboriginal leadership, were all at the same table. We came to an agreement on healthcare, on education, on water, housing and on accountability—it was a major step forward. Now, a new government came in, and I don’t want to be partisan, but they walked away from it. And I think they’re now beginning to realize they made a terrible mistake and they’re trying baby steps to pick up the pieces. Canadians need to understand the real discrimination against Aboriginal Canadians. When you talk to them about the underfunding of Aboriginal education compared to non-Aboriginal education, Canadians are outraged. So there’s a real opportunity here for some major steps forward.

As a final question, what was your personal reaction to what happened in Attawapiskat?

There are any number of villages that are in Attawapiskat’s position, and they were part of the motivation for the Kelowna Accord six years ago. Those situations are well-known. We’re allowing them to endure, and that the government attempted to blame the First Nations for this was just beyond the pale. When the government said it did not realize that that situation existed in Attawapiskat—when in fact the Attawapiskat leaders had met with previous Ministers of Indian Affairs, there’s no way the government didn’t know about it. For the government to attempt to blame the chief and her council, that is part of the problem. This constant attempt to blame the Aboriginal leadership for what is Canada’s problem, when the Aboriginal leadership has said, “For God’s sake, work with us please!” For the government to walk in and just simply say, “We’re going to dismiss your leadership and we’re going to take over”—it’s just wrong. I mean, if [First Nations communities] have a problem, [the government] has to work with them. They can’t just walk in and tell them what to do. We’ve been doing that for 300 years and it hasn’t worked.