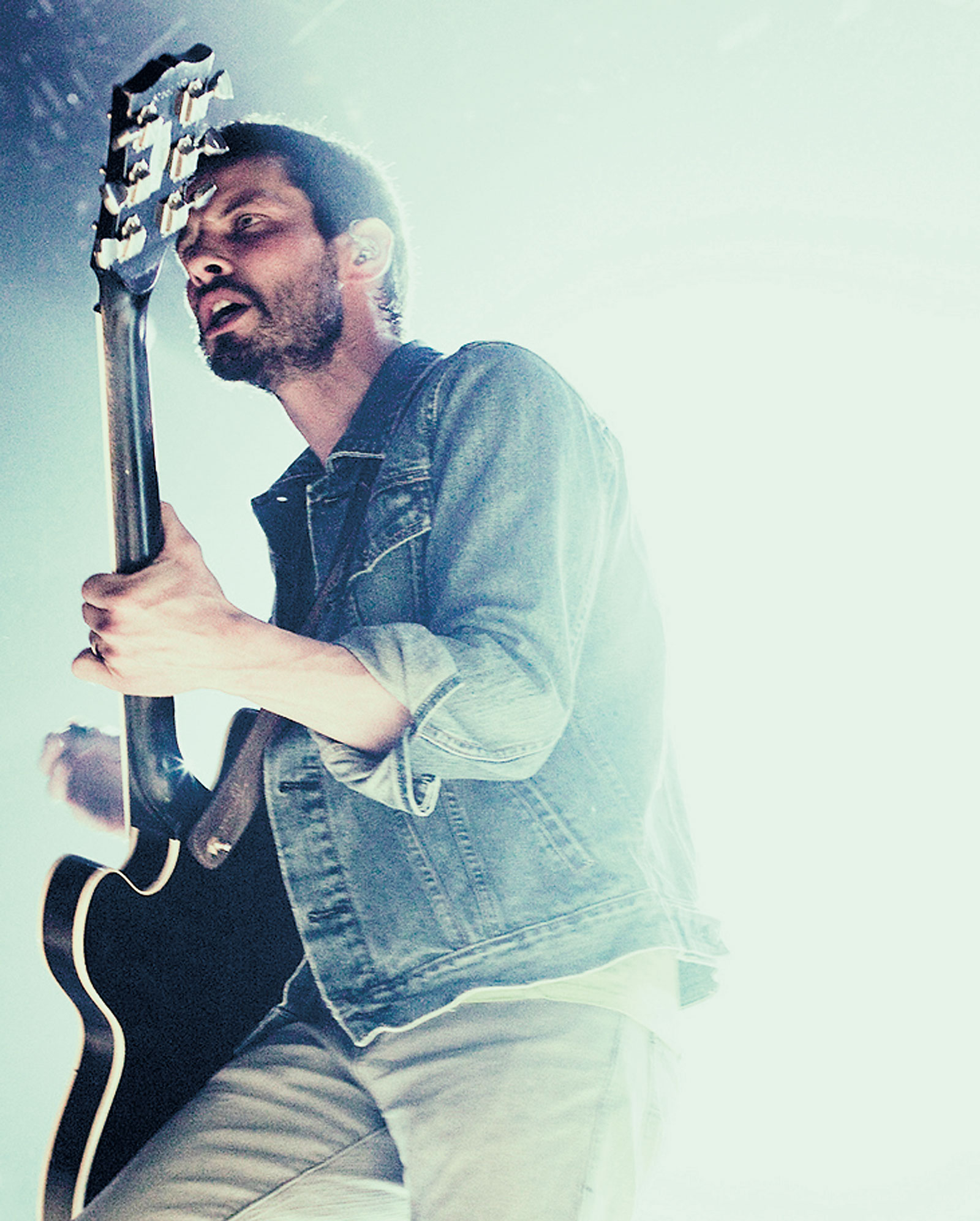

Consistency is an underrated skill—one that singer-songwriter Sam Roberts has perfected in the very core of his music. With five records, six Juno Awards, 10 nominations, and the accomplishment of having one of the best-selling independent records in Canadian music history, Sam Roberts has achieved something that few artists in the modern music industry ever achieve, even the successful ones: longevity. We talk to him about the importance of writing his own music, self-competition, and the difficulties of maintaining a balance between his musical intentions and the finished product.

Medium Magazine: I noticed that the cover of your most recent album, Collider, is the first of your releases to say “Sam Roberts Band” as opposed to just Sam Roberts. What brought about this change? Did you feel there was something that made acknowledging Sam Roberts as a band important to listeners?

Sam Roberts: Yeah. I think with this record it’s definitely been one that reflects the biggest contribution of the creative front that the band has made to date. It was an important step to not only tell people, but to recognize that the band is not just contributing on stage but also in the making of the record as a whole.

One of the recurring facts that tends to pop up is that your EP, The Inhuman Condition, became one of the best-selling independent releases in Québec and Canadian music history. Do you ever feel the pressure to top yourself or even self-compete—if not with your own record sales, then just with the past you: you as a writer, you as a musician?

Yeah, that was a hell of a way to start off. At the time I don’t think we knew it occupied any sort of space on the Canadian music hierarchy with any historical significance or value. The next record came out so quickly afterwards, I didn’t really have time to think about what I was going to do and whether it was going to have the same impact. And I find that with every record that comes, I’ve almost completely forgotten how I made the previous one. Even if I wanted to go back and retrace those steps, my life has changed in so many ways, my approach to songwriting changes constantly, that—again—if I wanted to go back there, I don’t know if I could find my way. So I just end up taking each new record as its own challenge and a reflection of a given period of my life, rather than rehash or recreate something from the past. And I think that’s just a healthier way to approach creativity in general.

With songwriting in mind, I know that with Collider and the rest of your recordings, you write all the music and lyrics yourself. How important is it for you to write your own music?

To me, it’s enormously important. It’s my outlet. It’s the way I get to exercise something that wants to come out of me. Everybody has a different urge or a different impulse in how they want to express themselves creatively. There are some things you can’t do in conversation, there are some things you can’t do in your day-to-day life; it needs to be said in different ways. For me, it’s always been writing songs and writing music. So when I sit down with a guitar, it’s just what happens. I just do it because it’s something I’ve always done and it’s something I’ve always wanted to do.

With something like your music video for “I Feel You”, the video—at least to me—feels quite dark and gritty.

Yeah, you’re on the right track, for sure.

So, with that in mind, are there themes that you feel continue to jump out or inspire you when creating visual counterparts for your music, like music videos?

It’s funny, there’s always a visual component to a song. Whether it ever gets made into a video or not, each song in my mind has a visual storyline. That can change from day to day, but it always seems to be accompanied by a strong visual. And they help me write the lyrics in the first place, in that the music itself often evokes a lyric which evokes an image and I can follow that somewhere. Videos complement it in the same way, and it’s always been an important part of what we do. The first video we ever made was for “Brother Down”, and we were on a lifeboat. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen it…

I have!

Yeah, it was a very low-budget video. We were in a lifeboat in the middle of Lake Ontario, and we eat—we cannibalize!—each other, as I remember [laughs]. It just started with that, and to me, I never really thought that it could be an expression of the lyrics or what the song is trying to say. In that sense, I like how [a music video] offers you an alternative version, or somebody else’s interpretation—the director’s interpretation—of what that song means to them.

With your most recent record, I couldn’t help but notice the sound is very relaxed, yet still “put together”. Are you finding it easier to write and record music as you progress through your career?

I don’t know if writing changes. It’s more about getting the time and space to think clearly about [the songs], getting off the road, and clearing my mind. In terms of the recording process, the more time you spend in the studio, the less nervous you are about trying things, or making mistakes, and the more you’re able to just play. Spending time in there and being under the gun and having the pressure of playing the song right takes time to grow into. I think that’s why the later records are now starting to sound more as if we were on stage, because that’s where I think the band is at its best—at its most effective and most relaxed.

When creating a song in the studio, do you ever think about how a song will translate for live performances?

Yes. Almost every time. Some of them I know are going to work well, other ones I have no idea whatsoever if they will work at all. Others I know for sure. There are a few records where we have songs that we just never play live cause they don’t translate at all live. It’s frustrating. I think with every subsequent record that comes out, we’ve tried to clean them out so we could play them live. Sometimes that requires a reworking or a completely new reinterpretation of the song. It presents an interesting challenge. Again, we don’t shy away from anything that pushes us or stretches our abilities… not that we’re a prog-rock band or anything [laughs].

Is there anything you try to do to help a song transition from the studio to a concert experience?

It’s always an interesting process when you’ve finished a record, and you’ve been sitting in studio mode for sometimes months and months on end. And you’ve been focussing so much on the details—and I mean details that are so microscopic— that they can become completely lost to you and everybody else. And then once you get back into the rehearsal hall, all that stuff goes out the window and you’re dealing with this raw palette of sound. It’s always a bit disconcerting at first, because the songs sound completely different to what you’re used to hearing on the speakers. So you kind of have to get over that and… fight it out, basically. I don’t mean that in a literal sense. You know, work that song until it takes shape again and it’s reborn in a live sense, and then you start to realize that the essence of the song is still there, and no, it doesn’t sound exactly as it does in the studio—and it’s not meant to sound like it did. That’s what live performance is about. It’s about giving a song a chance for rebirth every day. And they always come out differently. In that sense, you never stop writing the song, you never stop recording a song, and the album version is only one version, and not the definite version. The definite version doesn’t exist.

Nice. I like that. Now, with your new record, I know you collaborated with some great people, like Elizabeth Powell, Stuart Bogie, Ben Massarella, and Brian Deck (who also produced and mixed this record). Even as a musician who has accomplished so much, do you have any dream collaborations you ever think about? You know, people that are dead or alive—people you would just love to work with?

Oh man, there are so many people I would just love to create music with. You know, even just one time. Like Fela Kuti, one of my favourite West African legends. He’s gone now, but just to sit in and jam with him one time would be a dream come true—just to feel what it would feel like to sit in his band. We wouldn’t even have to collaborate; just give me a cowbell to play. For a night. I mean, just on a songwriting level: Paul Simon, Paul Kelly out of Australia—I really always loved his songwriting. The Happy Mondays. The Stone Roses. All these people that had great influences on me. You always wonder what would happen if you could connect minds with them. You know, what would come out. I mean the difficulty in a collaboration is sort of knowing how to work a give-and-take, an exchange of ideas. You kind of have to hold on to your own voice and thoughts, and yet be elastic enough to really accept somebody else’s way of thinking about music. To combine them together, that’s difficult to do, and it’s something I’ve been growing into. It doesn’t come naturally to me. I’m definitely open to it now, though, more than I ever was.

Great. One last question. You are a busy man, touring and recording, but when you have downtime, what do you, Sam Roberts, do to wind down or relax?

Not much anymore, since I have three kids! So, in fact, it’s busier at home than it is on tour. I haven’t figured that out yet. That’s the next chapter. I used to… well, if I could do anything, I’d go home and sleep [laughs], I could read books, listen to my favourite records, go out for a walk with my wife. And now… [laughs] Sorry, I’m just thinking about what it’s like when I walk through the door, it’s like… full throttle, all the time! Yeah, I don’t relax. I’ll relax 10 years from now… No, check that, I’ll relax 20 years from now! I‘ll go to an ashram in India with my wife and learn yoga. That’s what I’ll do. But that’s not for a long time. In the meantime, I’m either in a touring rock-and-roll band, or I’ve got a family to take care. It’s one of the busiest times in my life.

Well, if I talk to you in 20 years, I’ll hold you to that.

[Laughs] All right.