When we imagine a career in art, we might picture someone holding a paintbrush and preparing a wooden easel and white canvas in his small studio apartment. Alternatively, we might see a musician in a black leather jacket and bright red lip, strumming her guitar at the back of a dimly lit bar. We may not imagine, however, a graduate science student in her lab, grinding powdered charcoal and sketching fresh tissue.

Sana Khan, a Master of Science in Biomedical Communications student, is training to become a medical illustrator. The two-year program she is enrolled in is offered through the Institute of Medical Science in the University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine and engages students in the creation and evaluation of various visual tools with the goal of making science more accurate and accessible.

“Everyone who comes into this program is pretty artistically inclined. But something we really focus on is learning design principles,” Khan tells me, when we meet via Zoom. “How design and data visualization can account for the limitations of human cognition.”

Illustration has historically been an essential element of learning and understanding science, specifically human anatomy. Beginning in the Late Middle Ages and through the Renaissance period, anatomical drawings became an indispensable tool that revolutionized the study of biology and the practice of medicine. Belgian Renaissance physician Andreas Vesalius famously observed dissections of human cadavers and devoted his career to illustrating the first comprehensive textbook of anatomy.

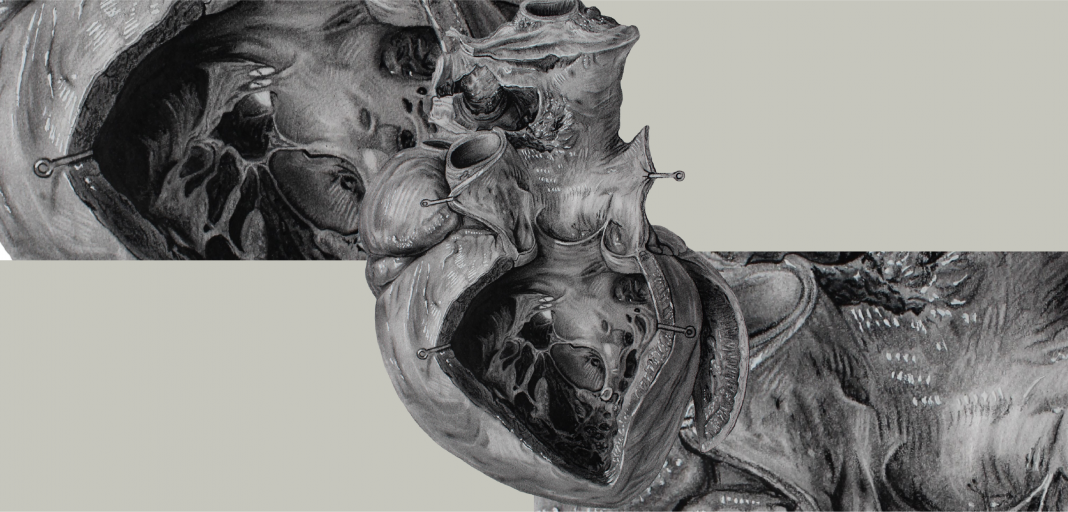

In 1894, Max Brödel, who was born in Germany and is now considered the father of modern medical illustration, arrived in the United States to work with clinicians at Johns Hopkins University. After graduating from the Leipzig Academy of Fine Arts and working for Dr. Carl Ludwig, Brödel gained a following for his prolific drawing techniques and eventually presided over the first Department of Art as Applied to Medicine in Baltimore. Over a hundred years later, medical illustration students still employ his practices, including the carbon dust technique which has enhanced the quality of scientific illustrations for physicians worldwide.

One such student of Brödel’s work is Khan. She grew up in Mississauga and, as a child, was always drawn to making art. Besides the occasional fine arts class in high school, she is entirely self-taught. Through free online resources, she learned her craft and discovered her technical ability. But when the time came to enter university, she decided to forgo any artistic pursuit and came to UTM with plans to major in psychology.

“I ended up specializing in neuroscience, as I was more interested in the biological aspect of psychology. Although for my labs, I sketched here and there, it wasn’t anything major, like how I was drawing before,” she recalls. But one day, serendipitously, she stumbled across a HuffPost article on this unique discipline that fused art and science. “It was kind of like a Eureka moment. When a light bulb goes on in your head and you’re like, this is what I want to do.”

This moment of clarity spurred Khan to assemble her admissions portfolio for the M.Sc.BMC program at U of T, one of only a few accredited graduate medical visualization programs in the world. Her focus is on still life illustration, but she is learning a variety of techniques such as 3D animation, user experience design, and virtual simulations, as well as training in anatomy as part of the curriculum. Importantly, the program, and profession more broadly, is research-intensive. Many of the details that medical illustrators visualize are undetectable to the naked eye or even under a microscope. Khan spends much of her preparation reading and developing a knowledge of her subject, so that her drawings are not only beautiful but scientifically accurate.

One of Khan’s illustrations from the past year depicts a human skull with searing specificity. The smooth forehead and sharp jawline with slight cracks and dimples in the bone she sketches render her plastic skull subject with exacting realism. Each time she sits down to work, her process begins the same way. To start warming her still life, she sets the object under a specific concentration of lighting and draws it from various angles. The detail and dimension that characterize her work are a result of expertly tailoring tonal values—her dark, medium, and light shades—on the page.

The most challenging part of her illustration process, however, is knowing when to put her pencil down. “It’s hard to make myself stop perfecting everything when it comes to art,” she says. An indicator of when a piece is finally finished is “when nothing looks out of place.”

In an era of misinformation amid a global pandemic, we have been soberly reminded of the gravity of science, facts, and transparency. Khan sees the role of medical illustrators as playing “the middleman who conveys complex scientific data. There is usually a group of people who never believes in the science but now, it’s just become so common.” To combat misinformation on a virus that has infected more than 100 million people worldwide, visual translation of evidence-based information into digestible infographics and images is key.

“You know that very viral image of the virus, the grey sphere with red spikes? That was done by medical illustrators at the CDC, who used scientific data to make it,” Khan explains. Knowledge is power and by understanding the world in which we live, we are more empowered to make informed decisions on how to better take care of ourselves and of others.

What Khan is doing, by combining her passion for art and advocacy for health literacy, is challenging the status quo and showing that art’s limitations extend beyond aesthetic purposes. “I think most people just don’t realize this is an option,” she says. “I’ve gotten requests from elementary school teachers asking if I can speak about the different career options in art. It doesn’t have to be your traditional sitting with the big sketch pad and charcoal pencil.”

———

It was during her interview season with prospective medical schools last March when Joanna Matthews first learned that Ontario was going into lockdown. As our generation begins to enter either the workforce or deeper training in our chosen vocations, Matthews is no different. When I spoke to her on the phone, she recently completed her four-week cardiology block—studying the human heart on Valentine’s Day no less—and tells me that she has finally found a rhythm for herself that balances coursework with time for self-care and reflection on this new chapter of her life. As a first-year Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) student at the U of T Faculty of Medicine, she was among the first class to be virtually inaugurated into the program. Although many of the pivotal moments she would have as a first-year student—from orientation week and meeting new classmates to visiting the hospital and interviewing her first patient—were compromised, she holds an experience of entering medical school unlike any other.

Matthews was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, and moved to Regina, Saskatchewan, when she was 5 years old. Her family is from Kerala, a state in South India, where Matthews would often visit as a child. When she entered grade 10, her exposure to psychology helped plant those initial seeds of her wanting to be a doctor. “What brought medicine into my identity was when I started seeing that I loved community service. I liked forming relationships with people and following up with them,” she explains.

At UTM, she majored in psychology and double minored in sociology and biology as an undergraduate student. She chose her programs “out of intellectual curiosity more than anything. I wanted to understand the mind and understand the fabric of society, and how different social systems interact with the mind. I really feel that’s what medicine is about—understanding how everything works together.” In addition to her course load, she worked at a child development psychology lab, directed by Professor Doug Vanderlaan, where she researched gender nonconformity in children. In an observational study of more than 400 kids, she looked at the differing influences of prenatal androgen exposure and socialization on gender-typed play behavior.

Her passion for working with women and children stemmed from this research with the Biopsychosocial Investigations of Gender Laboratory. As they are introduced to more classes, shadowing experiences, and clinical settings, medical students will decide on their specialty. But for now, Matthews knows that she wants to make a career in maintaining long-term relationships with patients, building expertise in one area of medicine, and pursuing advocacy work in her chosen field. “That’s being able to recognize which people require more resources or are disadvantaged,” she says.

The healthcare system in Canada is far from perfect and perpetuates many of the financial barriers and social disadvantages present in our society. Health inequity stems from the unequal distribution of care and health resources between different population groups based on social factors including education, income level, gender, and ethnicity.

In the past year, Covid-19 has distinctly highlighted how the dimensions of racial identity, age, and geographic location determine access to healthcare opportunities. The Black community in particular has been disproportionately impacted by the virus. According to a CBC report, 21 per cent of reported cases in Toronto affect Black people, though they make up only nine per cent of the city’s population. In regard to the delays in vaccine distribution, hospitals in rural areas are not equipped to serve as vaccination sites due to storage and shipping restraints. Consequently, rural Canadians must travel further to receive their vaccinations than residents living in urban and suburban areas.

“We’ve also seen how Covid-19 cases are represented in our long-term care homes. It shows how we might be neglecting certain populations and what we can do to improve things at a structural level,” says Matthews. The systemic inequity and inaccessibility to healthcare starts at the top and must be rectified by policies made by a collaboration between the medical community and local policymakers. “As personal support workers, nurses, and other healthcare workers, we have the insider perspective of what’s going on in different facilities or in more remote areas—all the behind the scenes aspects that need to be communicated” when devising policy.

Six months into medical school, Matthews has not only adapted to the steep learning curves of her classes and become a sponge for absorbing material, but she’s also grown as a person and as a woman. Science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) is known to be a notoriously male-dominated field, as women make up 47 per cent of the workforce in Canada, yet only hold 23 per cent of jobs in STEM. However, as girls and young women become increasingly involved with math and science subjects in school, interact with female mentors, and see diverse representation in leadership roles, Matthews believes that feelings of uncertainty and self-doubt can be replaced by feelings of empowerment and belonging.

“Seeing women thrive in those roles, you hold that subconsciously in your head when you’re making your own career decisions,” Matthews says. “One thing I’ve realized about womanhood is that you can balance being feminine while still being assertive in a way that sets your voice apart and allows you to shine. I constantly feel so blessed to be a part of this class where there’s a lot of amazing women showing so much initiative with all the projects they’re doing.”

Crises, including the pandemic we currently face, often bring out the extremes in people and illuminate where we fall short as a society. They can also finally put us all on the same page, revealing the kindness and ingenuity we are capable of together. In a constantly evolving world in need of truth and understanding, scientists are on the front lines. Khan and Matthews will be ready for their turn.