When I first started working on this article I thought two things. The first was that Google would give me some amazing and quick results regarding the history of teaching English Literature. The second was that students and professors would have similar reasons for studying English Literature. I was wrong about both.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “literature” as “the realm of letters”. This broadly encompasses all types of works, from journalistic articles to novels. “English” is a bit more difficult to define. English’s earliest ancestor was spoken in 450 A.D. and Chaucer wrote recognizable English in the 14th century, but the English we speak today is a long-refined combination of French, German, Norse, Latin, and Greek.

The study of “English Literature” began in the 19th century in English-speaking countries and was meant to increase nationalist sentiment. American students would study great American authors that described their great American nation. But today, English courses at U of T don’t focus on just Canadian writers; we have courses from Shakespeare to Chaucer to Jane Austen to Canadian diasporic literature.

So why study this subject?

Professor Chester Scoville of the Department of English and Drama says he studied English for “a fascination with what literature and language can do: the way in which they can create and move readers and audiences; the thick, visceral qualities of the kinds of language that people remember; the way in which they can make nearly any subject matter, however abstruse, approachable and discussable.”

Professor Chris Koenig-Woodyard has similar reasons: “Because of a love of language and narrative, and how the two touch on a number of related fields (culture, politics, history, to name a few)”. He adds that he likes “the play and pleasure of language, its metaphoric and musical qualities.” Professor Koenig-Woodyard “loves the transport and enchantment of narrative; that a story sweeps you up into the world of a book, poem, or play. Coleridge calls this the ‘willing suspension of disbelief’: readers and viewers stop questioning the fictional nature of a text, and immerse themselves in the constructed reality of a story.”

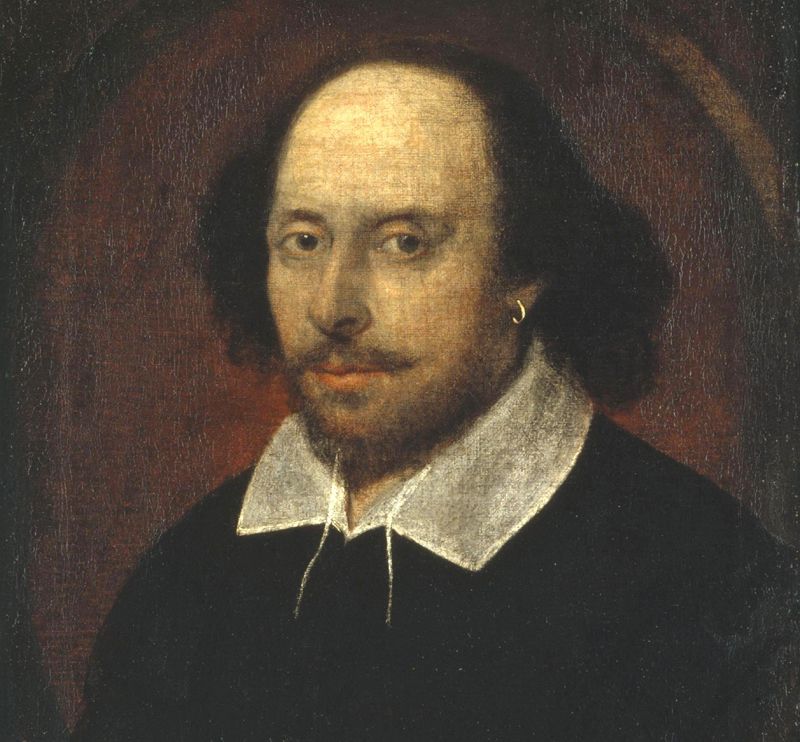

Students, on the other hand, focus more on exploring the sheer enjoyment of reading and exploring literature. Jasman Singh, a first-year double major in English and History, chose to study this field because he thinks “it’s the most interesting and educational subject there is! I mean, where else can you read the brilliant work of William Shakespeare? Not in chemistry, I’m sure.”

Other students have different views on how important English Literature is for them. Sara Notenboom, a fourth-year specialist in Psychology, with minors in Sociology and English, chose to study literature “because it delves into the human psyche and it is the recorded history of the human soul”.

The study of English literature has two aspects: one of simple enjoyment and appreciation, and the other, less famous, of analysis. When we read literature, for a short time we discover a different world, which often shows us real human emotion or a new experience. To enter and breathe this new world, to love good books for their own sake, is an important reason why some students choose to study English, but to look deeper and explain them lets the book speak its whole message.

The reason I chose to study English is much better phrased by the author Goethe; he called literature “the humanization of the world”. For me, literature captures the ideas of a culture, which could be the suffering during the Holocaust, broken friendships, time travel to an apocalyptic future, commentary on global warming and world pandemics, or anything else. In the end, though everyone has their own reason for studying English Literature, everyone that reads is a student of it. Maybe not everyone that reads this article is taking a minor, major, or specialist degree in English, but the written word is part of our everyday life, and we couldn’t survive without it.