During the Obama administration in 2015, under Democrat regulation, the United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC) passed net neutrality rules that maintained the internet as an open utility. The New York Times writes in a November 2017 article that the goal of the net neutrality regulations was to “acknowledge the essential role of high speed internet access as a gateway to modern communication, information, entertainment and economic opportunity.” The FCC, however, reversed these regulations in mid-December 2017.

While it will take weeks for consumers to see tangible differences as a result of this repeal, public interest groups in the U.S., such as Public Knowledge and the National Hispanic Media Coalition, have prepared to file lawsuits. Industry titans such as Google and Facebook, as part of the Internet Association trade group, have also said to be considering legal action, where Netflix U.S. tweeted “In 2018, the Internet is united in defense of #NetNeutrality. As for the FCC, we will see you in court,” on Jan 5, 2018.

The term “Net neutrality” was coined by Tom Wu, an associate professor of law at the University of Virginia between 2002-2004, to describe his vision for an internet where all traffic was treated equally by internet providers. According to him, reversing net neutrality regulations would deregulate telecommunications and cable industries.

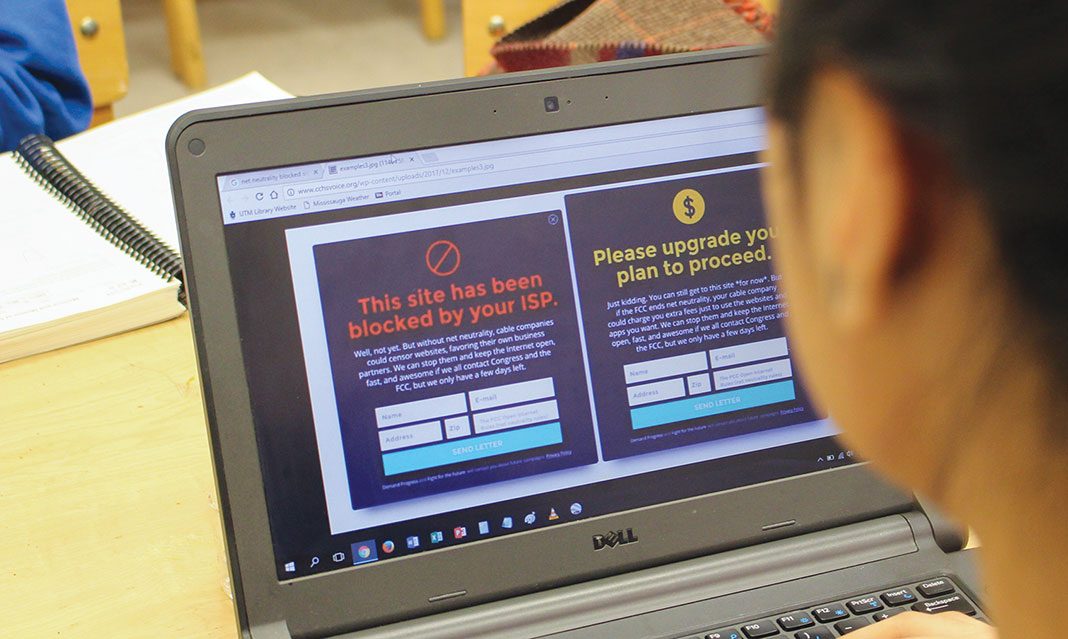

In simpler terms, the FCC removed the restrictions that prevented broadband providers from blocking websites and charging for higher-quality service, such as faster speeds or for specific types of content. The communications commission will also no longer regulate high-speed internet delivery as if it were open access, leaving access preferences up to the discretion of the service provider.

Professor Gabor Virag from the CCIT and management faculty at UTM states that net neutrality encompasses “non-economic values like freedom of speech, promotion of free media and democracy.” Virag further explains that the owners of the networks such as Verizon, Rogers, AT&T and Bell argue that the extra traffic is monopolized by just a handful of companies, like Netflix.

In a November 29, 2017 article by Quartz Media titled “The economic case that net neutrality was always fundamentally bad for the internet,” Dan Kopf presents two sides to the economic perspective. Katz, formerly chief economist at the FCC, argues for the benefits of paid prioritization, which is the ability of internet providers to charge companies for faster speeds.

The problem however, that Nicholas Economides, a New York University economist, anticipates, is that eliminating net neutrality will be detrimental for start-up companies. Start-ups, with relatively equal internet mediated operations, may face barriers while accessing high speed internet with an associated higher cost. By stunting innovation, Economides believes that a larger decrease in U.S. economic growth may also be observed.

Socially, there has been uproar against the repeal of net neutrality regulations because that would translate into a systemic barrier in accessing high quality internet for low-income families. Where social media is perceived as a catalyst in promoting social change over the past few years, open and free access to the internet allows marginalized groups to have a platform for voicing their concerns.

In the context of possible ripples being felt north of the border, Professor Virag says, “[The] Canadian context is probably similar to the U.S., but issues may come up more sharply as Rogers and Bell have bigger market shares in Canada than AT&T and Verizon in the U.S. They are also even bigger empire builders in terms of the content.”

The reason the fight in Canada hasn’t been as vocal, according to a Dec 14, 2017, article in CBC news titled “Why Canada’s net neutrality fight hasn’t been as fierce as the one in the U.S.” has been attributed to the FCC being a more biased and partisan organization than the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC).

Two years ago, during the Obama administration, the FCC ruled internet service providers were Title II common carriers, which regulates them as utilities, as opposed to Title I, which gives providers more control.

There is no distinction between the two in Canada. Matthew Brage writes for CBC news that in Canada, “Under the Telecommunications Act, internet service providers are treated like utilities, and there are rules around how they can act. There are two key rules in particular: service providers can’t give ‘undue or unreasonable preference’—say, to one application or online service over another—nor can they influence the content being transmitted over their networks.”

Analysts do not believe, however, that this absolves Canada from having clauses and conditions in the Telecommunications Act challenged. With the act up for review, advocacy organizations like Open Media are concerned that the indirect wording the CRTC’s net neutrality perception relies on could be threatened. “It doesn’t actually say the words ‘net neutrality’ in it,” Laura Tribe, executive director of Open Media, said of the act.

Open Media says that if any alterations are going to be made, it would be reassuring to see the protections made more direct.