Last Monday marked the third presentation in the Linguistics Brown Bag Speaker series, hosted by UTM’s Department of Language Studies. Students and faculty from the Department of Language Studies gathered in IB240 at 11 a.m. to listen to sociolinguist and Arabic specialist, professor Atiqa Hachimi, and her ideas about gender, style, and Arabic language ideologies in a digital world.

Hachimi has been with the University of Toronto since 2009. She currently teaches undergraduate courses at the Scarborough campus, under the Department of Historical and Cultural Studies, and graduate courses at the St. George campus.

“I shall be talking about the hierarchy between North African Arabic varieties and those [Arabic varieties] spoken in the Middle East,” Hachimi explained at the beginning of the talk. Her research on sociolinguistic hierarchy in the Arabic-speaking world is part of a larger project on Arabic language ideologies and politics of gender and identity in the Arab-speaking world.

“People from North Africa and the Middle East, when they come together, who accommodates to who?” This is the question that guides much of Hachimi’s research work.

Language ideologies, as the sociolinguist mentioned, refer to the attitudes and beliefs people hold about language. “We have all sorts of ideas about language, about its correctness, about its presumed purity. What counts as a pure linguistic form?” She questioned.

“We are agents of language policing,” said Hachimi, “We are policing language. This is how we divide what language is, what it is for, and what it is worth. There are some language varieties that are [considered] more valuable than others.” She went on to explain when and why language policing mattered. She mentioned that a person speaking non-standard English or French during a job interview would likely not get the job, especially if the job interview required standard English.

“Language ideologies are never ever only about language. They are always about something else […]. It’s either national identity, gender [or] what counts as moral or immoral,” explained Hachimi. The Arabic specialist elaborated that policing a way of speaking goes beyond policing language; it polices morality, sexuality, and gender relations, which is why language ideologies are very important for sociolinguists to consider.

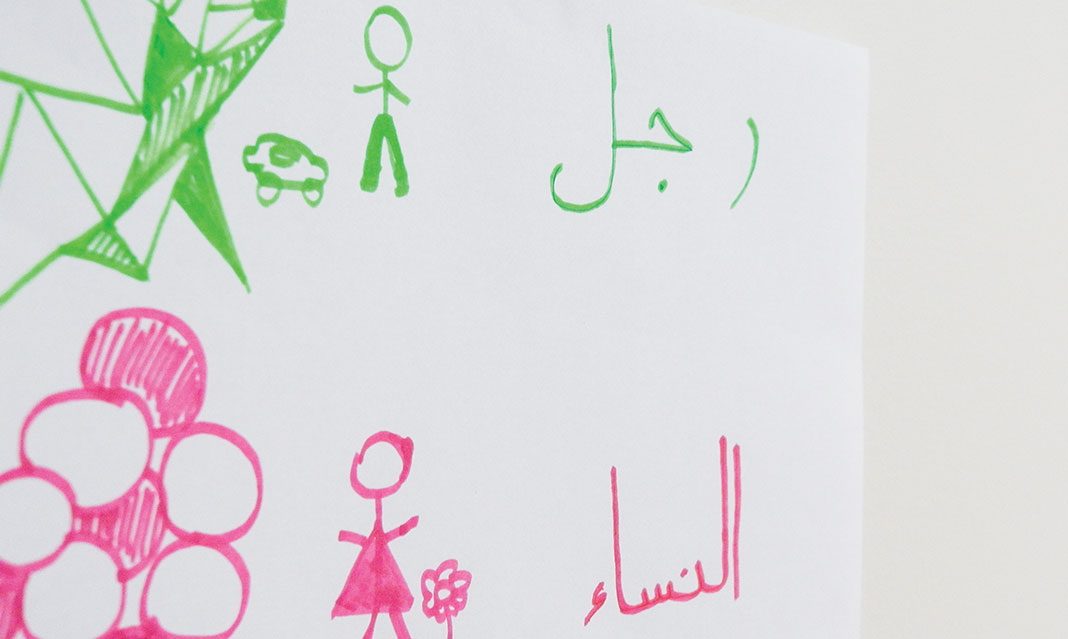

The professor then shifted gears towards Arabic, her area of specialty. “There is no one who speaks standard Arabic as a native language,” she informed the audience, “We just don’t. There is no one who does that. What we speak are these vernacular varieties.”

“If you use it, then you’re either a foreigner and you will be laughed at […]. It’s like growing up speaking Shakespearean English,” commented Hachimi.

According to Hachimi, most countries have their own dialects of Arabic. These dialects vary depending on the region; there is Nigerian Arabic, Syrian Arabic, Gulf Arabic, and Moroccan Arabic, to name a few. Hachimi’s research focuses on Moroccan dialect and its place in the hierarchy of Arabic varieties.

Morocco is a country in North Africa, and like many North African countries, the variation of languages spoken by residents is a mix, including Indigenous languages, Arabic, and colonial languages. In Morocco’s case, the Indigenous language is Berber and the colonial language is French. This mixing of language has given birth to the notion that North African language is inherently non-Arabic. This has led to an unequal relationship between North African Arabic varieties and Middle Eastern Arabic varieties.

Hachimi recounted that people say to North Africans: “You’re not Arabic, you don’t speak Arabic; you speak this mishmash of French and Berber and Arabic so you’re not speaking real Arabic.”

This unequal relationship is seen where people speak North African Arabic on Pan-Arab shows. The North African dialect is subtitled in standard or Middle Eastern Arabic, where the emcees and judges of said shows predominantly speak Middle Eastern Arabic. North-African dialects, as Hachimi mentioned, become an object of mockery on these shows.

Hachimi explained, an expectation is formed where people who don’t speak “real” Arabic need to accommodate on Pan-Arab shows by converging to a “real” dialect. Moroccan popstars who appear on these shows often do converge, and while this decision may garner the popstar more fans, it has also resulted in a lot of backlash from Moroccans.

Hachimi presented case studies of two female Moroccan stars, Dounia Batma and Mouna Amarsha, both of who appeared on Pan-Arab shows where they spoke in Moroccan Arabic to appeal to Moroccan voters. However, they converged to other Arabic varieties—Batma to Egyptian Arabic and Amarsha to Gulf Arabic—after the shows ended. “Women are [considered] repositories of cultural authenticity and purity,” explained professor Hachimi.

“Anxieties about language ideological debates, whether implicit or explicit, are not exclusively about language,” says Hachimi, “They unravel—as I hope I have shown—the complex relationship between linguistic practices, morality, and today’s conceptualization of Moroccan national identity.”