Memes can be funny, wholesome, political, dark, offensive, niche, universal, or a combination of all these types. In fact, meme types are as varied and unique as jokes because internet memes are, at their core, an inside joke for a community. The size of that community differs greatly, and some memes are able to permeate through to multiple communities and go mainstream. The life cycle of a meme is contingent on the community as well. Memes are created, shared, reach the mainstream (go viral), get recycled, die, and are resurrected because of how communities make, share, and use those memes. The important fact is that memes are nothing without the context from which they emerge, evolve, and die.

There is a widely held belief on the internet that once a meme has a think piece written about it, it is considered dead. Essentially, when the meme reaches a critical mass that catches the attention of writers and compels them to produce analyses about the meme, the meme loses its appeal as a joke because jokes aren’t funny when you explain them. However, this notion of thinking about and perceiving memes as just an internet joke that is shallow and not indicative of a wider social or cultural phenomenon is reductionist. It is also used as a shield for those who use memes to attack or offend other communities since they can laugh it off as a harmless joke.

Yet, memes, like jokes, are a more insightful cultural artifact than we often think because they provide a lot of information on how we experience and comprehend our world. Memes react and comment on real world issues, from the new “Fleets” feature on Twitter to the U.S. election. Memes are also used by both sides of the political spectrum, with groups using them to spread their message or attack one another. For example, many of the original memes that came out of sites like 4chan were deeply problematic, such as “advice animals,” which often contained violent dehumanizations. “Pepe the frog” is another meme that was appropriated by white supremacists, and while the majority of Pepe memes aren’t racist, the context in which a Pepe meme appears can be very telling.

As a new editor of a section that hadn’t had a sole editor before, I knew I needed to grow my base of writers and generate engagement to keep the section going. Every Sunday, I send out a call for article ideas. I needed an effective, quick, and engaging way to encourage students to write for my section. To do that, I turned to memes. Using different formats, I would use the meme to convey the same message again and again: send me your pitches. The difficulty in this method is that not all currently relevant memes can be used for my purposes. Meaning that sometimes I have to dive into older memes, those that are considered dead or on the brink of irrelevance and obscurity. When sifting through these older meme formats, my biggest challenge is that I was either unsure or unaware of the proper meaning and use of that meme. My biggest concern was using a meme format that held a different contextual meaning that would impede my message for those who still remember the meme.

It is through this dilemma that I discovered the meme research and documenting website Know Your Meme. Founded in 2008, this site is the work of an editorial and research team, as well as their registered members, that work to preserve the context of memes so that they can be understood after they have lost relevance and been discarded. While their work may seem cringe to some, archiving our cultural discourse found in memes is an important resource when analyzing a social movement, political moment, cultural belief, and more. Just like Tweets, Facebook and Instagram posts, Reddit threads and all the other ways people communicate and engage in their online community, memes are an integral part of cultural evolution.

That cultural evolution has also led to a change in meme consumption. Memes have moved away from being spontaneous jokes to a more carefully manufactured form of marketing or propaganda. Companies, institutions, political campaigns, and special interest groups all use memes as a tool to influence and engage as many people as they can on the internet. One recent example is Marianne Williamson’s campaign after the first Democratic debate in 2020, where she began to use memes in her campaign after being memified herself.

There are even companies that specialize in manufacturing memes to sell. This shift, coupled with an increase in overall internet consumption and the easy dissemination of memes through social media, all contribute to rapid meme death. Rapid meme death is a phenomenon where memes quickly die or lose relevance in the space of a few days to a few weeks. While older memes have stuck around for longer, newer memes tend to have a shorter lifespan before being recycled or discarded. Of course, this doesn’t apply to all memes. For example, the “Distracted Boyfriend” meme has been around for three years now, constantly evolving and even getting a gender-swapped version.

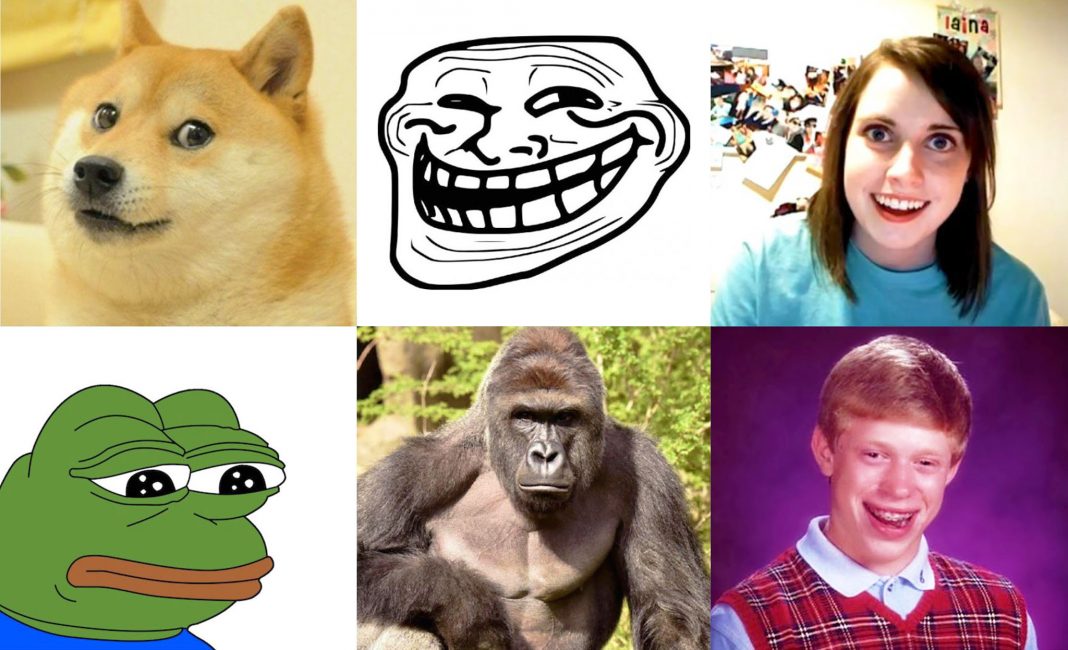

In the end, memes like “Bad Luck Brian,” “Overly Attached Girlfriend,” “Trollface,” “Doge,” “Damn Daniel,” and “Harambe” all come from a context. In order to understand those memes years later, we need to preserve that context so that we can learn about our internet past. In essence, memes are the internet’s hieroglyphic language, comprised of images and symbols. The think pieces, archival records, and newsfeeds are the Rosetta stones that will allow the next generation of netizens to understand the memeified past.