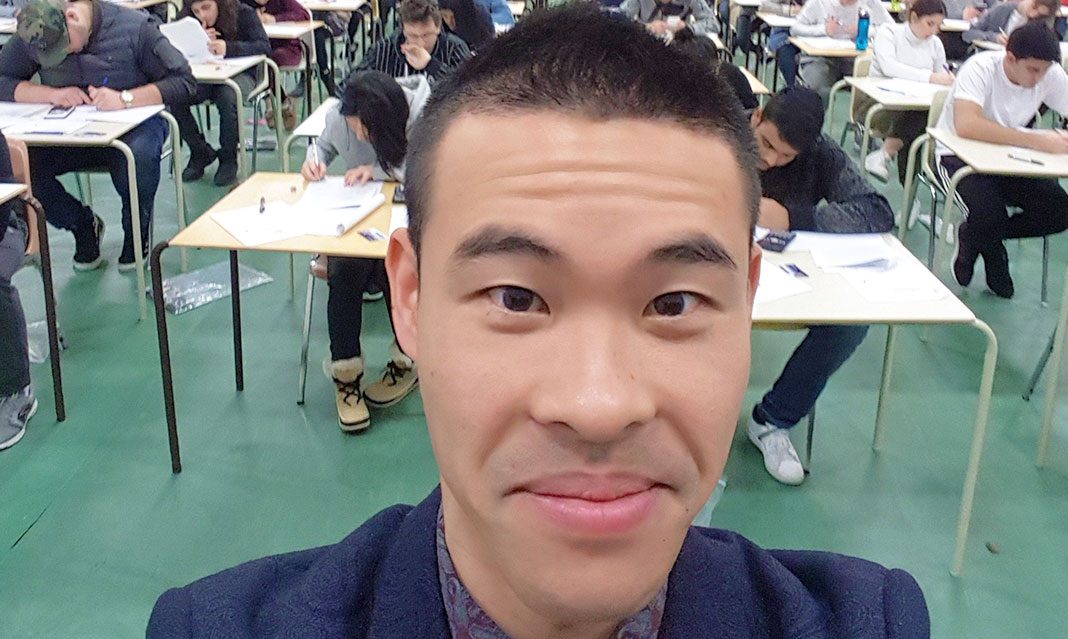

Mitchell Huynh, a sessional lecturer in the management program at UTM, has made national headlines for making students purchase a copy of his book, get it signed, and follow him on social media to earn participation marks.

He has been met with fierce criticism this past week, with many regarding the sale of the book and the additional social media followers as, well, stupid.

Huynh isn’t the first professor to assign his own book as a course resource, and through his interviews he’s been insistent on the fact that the amount of money that he makes from book sales is marginal. “Teaching and book sales together are less than five per cent of my annual income,” he told the National Post. The book is listed on Amazon for $20 – certainly less than textbooks in most courses.

Huynh might believe that he is helping students by providing them easy grades for doing something that consists of little effort and cost only $20. But there is a larger issue that people have a problem with, and that is what Huynh represents: why would someone trample over the downtrodden?

Students are already paying hundreds of dollars for his course, so why should they be forced to buy his book and follow him on social media? To the people that are in his course, my piece of advice is this: just do it. My personal experiences at UTM have been underlined by the ability and power that instructors have within their courses, and as evil as you might perceive Huynh’s requirements to be, there are other courses that would get you to pay a much larger sum of money to fully participate (i.e. cost of textbooks, TopHat, iClickers) and most importantly, his requirements will generate easy marks.

The larger issue that I take with Huynh is the cult-like personality that it appears he is looking to create. To be completely fair: I have never met Huynh or taken his courses, but from the personality that he is attempting to create and sell online, it appears incredibly disingenuous. Just as there are professors on this campus that regularly place textbooks on their syllabus that cost more than $20, there are also instructors that make the conscious effort to include readings that are available to students through the tuition that they are already paying.

Some of the greatest professors that I have had are ones that genuinely concern themselves with the well-being and success of their students. From the video that Huynh posted on his Instagram in response to the backlash, it appears that he prioritizes his success, referencing to the fact that he regularly receives great testimonials from students from course evaluations, that his course is a very highly rated one and that the book shows his students how to create additional income.

His inability to focus on the real issue at hand—his students—and his focus on what is more interesting—material wealth—is evident through the comments that he makes, encouraging his students to use his book as a “wealth bible.” He then points to the fact that the notes that students make throughout their university career will probably end up discarded, but “the minute that you spend money on something […] it is now something that is more valuable.”

If he’s not making any money off his book and teaching, then why continue? His genuine care for his students? Only Huynh can answer that. But the fact of the matter is that through this position that only brings in five per cent of his annual income, he’s gained a lot of clout.

Perhaps Huynh, like some other professors, should make a conscious effort to be more in tune with caring for his students by making teaching more personal, a quality that is easily forgotten within the size and prestige of U of T. However, under the assumption that he cares for his students, Huynh represents a type of professor that could learn just as much from his students as he thinks he could teach them.

Huynh also associates the inherent value of something with the fact that one pays for it. He shouldn’t forget that his course isn’t free, and neither is the time of his students.