“Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life, and it ought not to be.”

After Charlotte Brontë sent her poetry to the poet laureate Robert Southey, these were the words he wrote to her in a letter—10 years before she published Jane Eyre.

From past to present, gender expectations have made the world more challenging than it needs to be. Literature is just one area where women have faced prejudice for years, reminding us of how much power a name can hold. It was a strong possibility for works to be rejected just because of a female name on the front. But women writers believed in their writing and wanted to see it published—even if it meant adopting a male pen name to make it happen. Many famous pieces of literature that we recognize even today were a result of this strategy, proving the skill of writing that women can have and the strengths which made their works iconic.

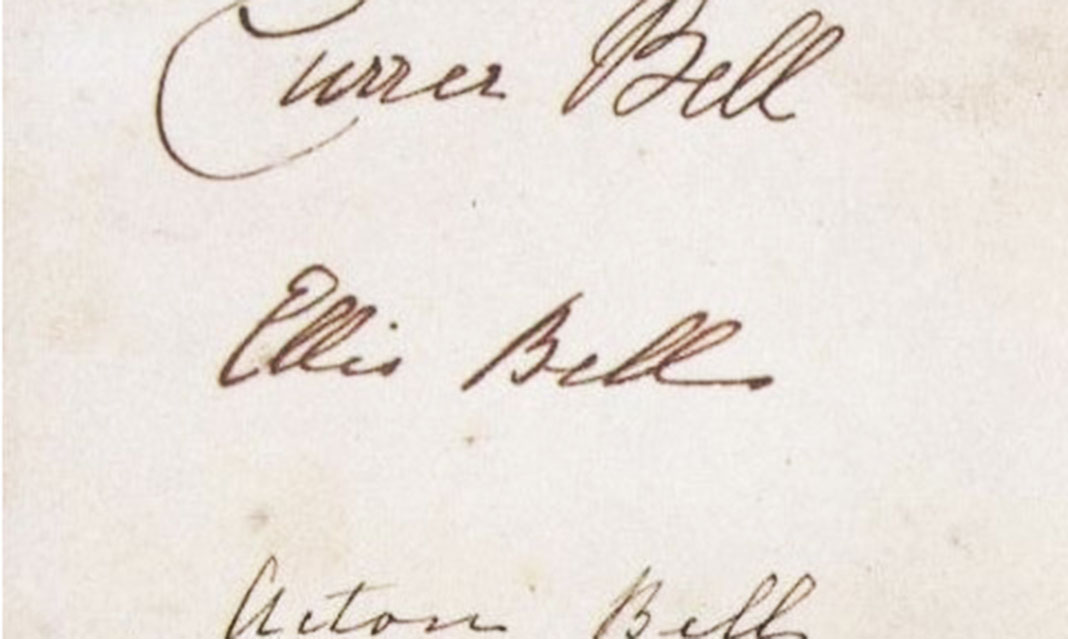

The Brontë sisters—Charlotte, Emily and Anne—were among these women writers who wrote under male pen names and went on to produce popular novels. Charlotte first published Jane Eyre under the pseudonym Currer Bell. Emily, who wrote Wuthering Heights,went by the pen name Ellis Bell. Anne chose to write as Acton Bell and published The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. The three sisters wanted to avoid that prejudice as they thought people would criticize the elements of their work that were not considered ‘feminine.’

Author Louisa May Alcott also took a male name of A.M. Barnard for the same reason of wanting to write elements which would not fit with society’s image of ‘feminine.’ Alcott is most famously known for her novel Little Women, which was published under her own name, but had to become A.M. Barnard to write gothic thrillers like Behind a Mask.

Science-fiction was another genre that seemed male-dominated at the time and not ‘ladylike.’ Alice Bradley Sheldon, now famous for science fiction works like The Girl Who Was Plugged In, chose to publish under the name James Tiptree Jr.

“A male name seemed like good camouflage. I had the feeling that a man would slip by less observed. I’ve had too many experiences in my life of being the first woman in some damned occupation,” said Sheldon in an interview with Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction magazine.

George Eliot is another name that may sound familiar but belongs to author Mary Ann Evans. Under this name, she wrote novels like Middlemarch and The Mill on the Floss. Another recognizable name is author of To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee, who is also a woman that purposely chose a less feminine-sounding name. By dropping her first name, Nelle, her identity remained ambiguous. Another strategy for a more gender-neutral name was to publish under initials. A modern example would be J.K. Rowling, most famous as the author of the Harry Potter series. For a more neutral pen name, she took the letters of her first name Joanne and her middle name Kathleen. However, she also chose to publish another book, The Cuckoo’s Calling, under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith.

Though times have changed, prejudice still lingers, prompting the continuation of male pseudonyms. Other than these examples, there are many more women writers who chose a male pen name to escape that judgement based on their feminine name. Even in modern society, author Catherine Nichols, a more recent example, conducted an experiment where using a male name brought in 17 manuscript requests versus the two requests she received using her own name.

These problems of prejudice may seem timeless, but with the survival of iconic works by authors like the Brontë sisters or Nelle Harper Lee, the timelessness of women writers’ success show as well.

Considering it