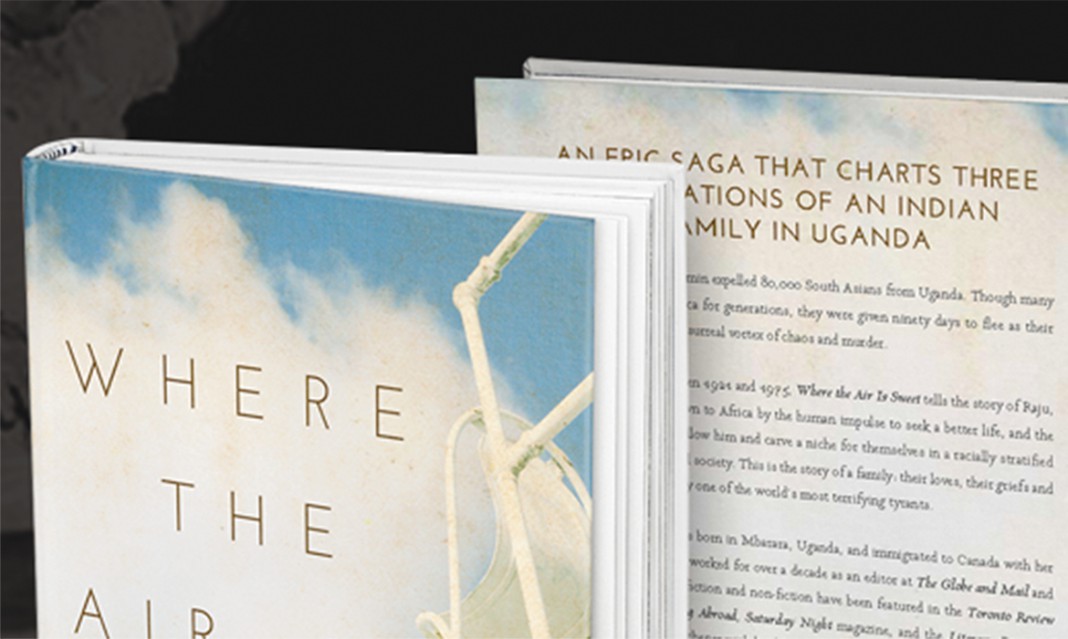

I read Tasneem Jamal’s Where the Air Is Sweet in the span of two days over the summer. In her blog, Jamal describes the novel: “In 1972, dictator Idi Amin expelled 80,000 South Asians from Uganda. Though many had lived in East Africa for generations, they were forced to flee in 90 days as their country descended into a surreal vortex of chaos and murder. Spanning the years between 1921 and 1975, Where the Air Is Sweet tells the story of Raju, a young Indian man drawn to Africa by the human impulse to seek a better life […] Where the Air Is Sweet is a story of family, their loves, their griefs, and finally their sudden expulsion at the hands of one of the world’s most terrifying tyrants.”

Jamal has written fiction and non-fiction for several publications such the Toronto Review of Contemporary Writing Abroad, the National Post and The Globe and Mail, where she worked for 10 years as an editor and journalist.

I spoke to Jamal about her first novel and her family’s experience moving from Uganda to Canada during the expulsion organized by Idi Amin in 1972.

I did nothing in my spare time this summer but read, and I was so drawn into the lives of the characters and their stories that emerging from that world at the close of the novel was a slightly jarring experience. The characters continued to live with me for quite a while afterwards, and Where the Air Is Sweet is definitely among the books I will read again.

The Medium: How much personal experience did you draw on to write Where the Air Is Sweet?

Tasneem Jamal: I couldn’t draw on much personal experience because the majority of the novel takes place before I was born. But I do use my family’s experiences to paint the broad strokes of the story. My grandfather left the Indian state of Gujarat in the 1920s and began to build a life in Uganda, as Raju does. He settled in Mbarara and ran a tin mine and an automobile business, as Raju does. As well, my family, like the family in the novel, was expelled from Uganda in 1972 and eventually settled in Kitchener. Though the character of Raju is inspired by my grandfather, no characters in the book are real or representative of anyone in particular, despite similarities.

TM: Do you get sick of people asking you that question?

TJ: It’s a reasonable question considering the fact that the novel is based on historical events. What I find somewhat frustrating about the question is that its premise is disputable. Whether I’m relating events that really happened or whether I’m making something up purely from my imagination, I can speak only to my perceptions. In other words, I’m not convinced there is an objective reality. My perception of a person or event is my story of the person or events. Another person would have his or her own story of those seemingly same events. As you can see, this answer can become philosophical very quickly. The point is fiction and reality are not mutually exclusive, in my view.

TM: What do you think are the most important themes in this novel?

TJ: Migration and the notion of home are the primary themes. Why do we move? What compels us to leave what we know for what we cannot imagine? And what constitutes home? When does a place become our home, if it ever does?

TM: Which of these themes did you deliberately include? Were there any that occurred unintentionally?

TJ: I included the themes of migration and home deliberately. These are issues I’ve grappled with most of my life, as an immigrant and as a person who was part of an ethnic cleansing. Some other themes that emerged as I wrote include questions about compulsion: What is the cost of resisting forces in our lives? Why is it so difficult to let go of what we are and what we know, even when letting go offers safety? For example, how does a racially stratified society affect relationships both among one’s racial group and with people outside one’s racial group? Or in a strongly patriarchal culture, is it possible for a man and woman to relate in loving and meaningful ways?

TM: Which books have changed the way you write, in terms of either style or content?

TJ: I was and continue to be inspired by Charlotte Brontë, particularly in her depiction of isolation and in how she conveys—and she does this subtly and powerfully—the darkness in her characters. J.M. Coetzee, especially in Disgrace and Foe, and Ernest Hemingway, in his entire oeuvre, write tight, powerful sentences, which is something I strive to do. Jhumpa Lahiri in all of her fiction has a style to which I aspire and that I think of as unadorned. I consciously write in a manner in which my words do not get in the way of the story. I like to imagine that the reader forgets she is reading when she is immersed in my novel.

TM: Which character do you identify the most with and why? Do you have a favourite character?

TJ: There are aspects of each of the characters that I identify with, but overall I would say I identify most with Mumtaz: as a woman who feels comfortable with her intellect, a mother of young children, someone who is insecure in her sense of home and place in the world, and as someone who comes slowly to the awareness of her power and agency. I can’t say that I have a favourite character. They are all important to the telling of the story and I value them equally.

TM: What were the challenges of writing from several different perspectives/voices? What were the rewards?

TJ: One of the greatest gifts writing fiction gives me is the freedom to explore many parts of my personality. I have always had a vast internal life brought on by a somewhat difficult early childhood. Writing in different perspectives allows me to explore the various parts of myself that have not had the opportunity for free expression.

TM: Was it difficult to write from a male perspective?

TJ: I found it remarkably easy to write from a male perspective. I grew up with brothers and was a tomboy, so I enjoyed this particular perspective. Nevertheless, I asked my husband to check over some sections in early drafts to see if they rang true to him. They did.

Jamal is a Globe and Mail editor and journalist turned novelist.