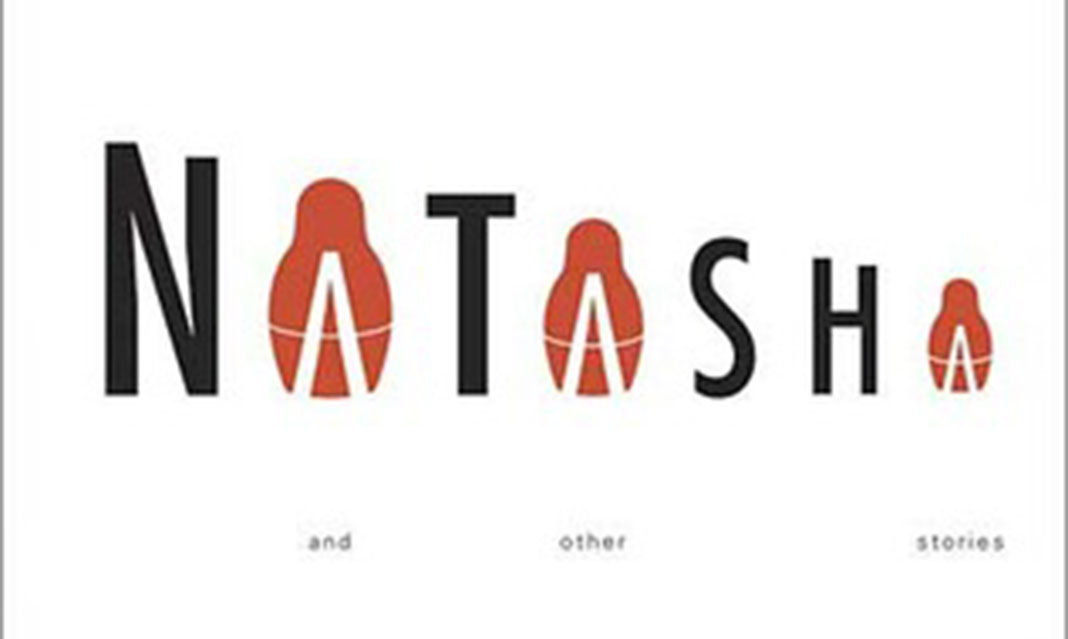

First published in 2004, Natasha and Other Stories is the debut work by Canadian author David Bezmozgis. An immigrant himself, Bezmozgis explores the lives of a Russian-Jewish family and their immigrant experience in Canada. The book is comprised of several short stories that connect in many ways and are told mainly through the perspective of the protagonist, Mark Berman. The first story, “Tapka,” details the Berman family’s arrival in Toronto, Mark’s elementary school days, and his memories of a neighborhood dog named Tapka. The story takes us through Mark’s experience, among others, of learning new vocabulary, swear words, the concepts of responsibility and guilt, and the cruel exorbitance of veterinary fees.

Several stories in the text delve into the issues of social status, markers of wealth, and upward mobility. In “Roman Berman, Massage Therapist,” Mark’s father, alongside working at a chocolate factory, struggles with difficult English-language medical texts in order to get a license in massage therapy––work that he had previously done in Latvia without any accreditation. The story offers a glance into immigrants striving for better work in order to lead better a life. As evidenced by Roman Berman’s initial unsuccessful months running a therapeutic massage business, economic advancement for immigrants does not seem to be easy by any means.

A recurring theme in the stories is identity and its intersectionality. Bezmozgis explores the intricate ways in which cultural, religious, sexual, and social identities intersect. For instance, the story “An Animal to the Memory” maps Mark’s Hebrew school days, cultural conflicts within the Jewish-Canadian community, as well as the remembrance of Jewish persecution on Holocaust Day. The story illustrates how intergenerational trauma conflicts with Mark’s internal struggle for identity––which turns out to be a lifelong, endless endeavor. Trauma also plays an important role in the titular “Natasha,” which depicts the effects of troubled pasts, the thrills of sexual awakening, and the first instances of maturity.

The stories are arranged in chronological order, mapping Mark’s growth from childhood into adulthood. However, Mark lurks in the background in a few of the stories, where other characters are given the spotlight. The text reveals several glimpses into the lives of the Jewish immigrant child, teen, adult, and elder, forming a spectrum of individual experiences. With the final story, “Minyan,” Bezmozgis portrays the lives of elderly Jewish-Canadians, and how even on their deathbeds, people grapple with their identities. The text not only deals with the specifics of the Jewish-Canadian immigrant experience, but also the broader issues of how others define individuals and how individuals define themselves.

Natasha and Other Stories happens to be a course reading for ENG424, a Canadian Literature seminar taught by Dr. Hill. In our discussions, an argument arose about the narrative structure of this text; whether it is a novel or a short story collection. It turns out that the argument itself is wrong to begin with, since both those structures are European. As readers, we would do well not to inject our own perceptions onto marginalized authors and their work. Only Bezmozgis can attest as to the structure of his text and how the form speaks to his individual identity. Natasha and Other Stories is required reading not just for Canadians, but for anyone who wishes to understand the complicated connections between collective and individual identity, the burden of representation for marginalized creators, and their struggle with freedom of artistic expression.