When the ones we love pass away, there’s a void in our lives. But their stories don’t end when their life does. What if there was a way to encapsulate the richness of a person’s history in a piece of artwork?

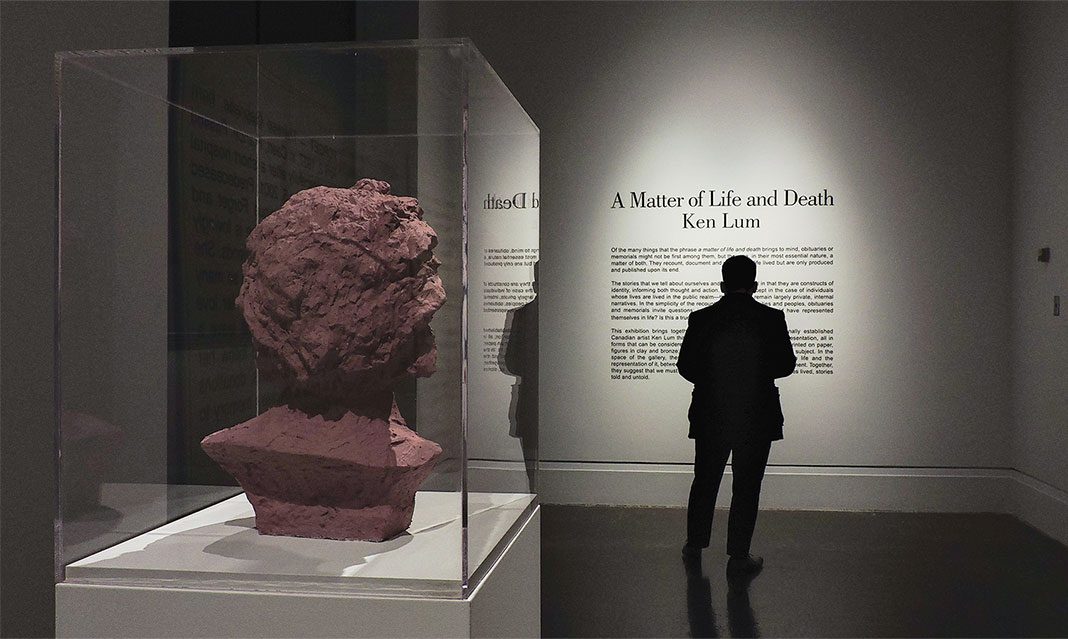

Ken Lum’s new exhibition at the Art Gallery of Mississauga, A Matter of Life and Death, achieves this feat. Lum’s work represents human life through memorial busts and text-based paintings of obituaries. Lum has been an established artist for over 35 years, producing conceptual art through sculpture, paintings, and photography.

When I first entered the exhibition, I was drawn to six memorial busts. Lum moulded each bust from plaster, modelling the faces from Philadelphians. The people in the busts all underwent public scrutiny to some degree. For example, one bust depicts Kathy Chang, better known as Kathy Change. Chang was a Chinese-American performance artist and political activist who performed one-woman shows of her dancing, singing, and guitar-playing on the University of Pennsylvania Campus to protest the government. In 1996, Chang took her own life by lighting herself on fire in front of the peace sign on campus.

Another bust portrays Birdie Africa, one of two survivors of the 1985 Philadelphia Police bombing of MOVE, a black liberation group. Africa was only 13 years old at the time of the bombing, and soon became the face of MOVE. He died in 2013 of an accidental drowning.

Lum sculpted each bust with extreme detail. As you peer into their eyes, the effect is haunting—after you read their story, you can almost see the individual emotions on their faces.

In the larger room of the exhibition, eight prints made with archival ink line the walls. Each print is in the style of an obituary, all using different fonts. The “obituaries” create a narrative for each person’s life. Lum’s inspiration for this series stems from his discovery of the front page of the Philadelphia Inquirer, published for Abraham Lincoln’s death. To commemorate his life, the newspaper took Lincoln’s major life events and wrote them as headings. Lum plays with different obituary styles from different eras to see how they affect the way someone’s life story is depicted.

For example, one work called “The Mystery of the Tattoo Lady” depicts the character Jade Visscher’s death as a mystery. The piece tells the observer that Jade’s body was unidentified for several days and the cause of death was inconclusive. It was only when the investigators saw photos of her “distinctive tattoos” that they discovered who she was. This work depicts a life that has many unanswered questions, even after her death. And because the secrets of her death will never be revealed, her life is documented with a sense of mystery.

One of my favourite prints is “Kim Sook Joo.” This “obituary” depicts the short life of a girl who died at five days old. The obituary lists all the names of her great-grandparents, and all the names of people in her extended family that survived her. At the end of the “obituary” is a quote that says, “A family is a little world created by love.” This piece emphasizes the presence of family in the subject’s life. Although the child did not live long, her memory is carried on through the rest of her family.

Lum blurs the lines of fiction and biography by taking key details of a person’s life and documenting them in ways that exhibit their life stories. Lum’s work forces the viewer to ask themselves: Is this the way the dead would have wanted their life story to look? What key moments in a person’s life contributes to their overall identity? A Matter of Life and Death also leads the observer towards self-reflection. How would we want to be remembered by others?

The second new exhibition at the AGM is Somewhere Else by Nam Phi Dang. Dang’s exhibition consists of five photographs from a larger photo essay that came from his 2015 trip to Vietnam. His parents left Vietnam before he was born, so Dang wanted to return to their native country to establish a connection.

Dang’s photos contain seemingly fleeting and mundane moments to the superficial eye. But upon closer examination, they have a dream-like and “alternate world” quality to them. For example, in “Flower Village in Hanoi,” we see an apple tree elevated on a platform. Vietnamese women of different ages stand or sit on the platform using their phones. Surrounding them are fields of red, white, and purple flowers. In the background of the image, we can see small buildings, perhaps belonging to a rural town. The settings of a rural landscape contrast with the women using new technology. This dual imagery emphasizes the feeling of displacement individuals experience after moving from one country to another. Dang felt this way when he travelled to Vietnam, as Vietnamese culture was neither the same when his parents left, nor was it the same as Dang’s experiences growing up in Canada with a Vietnamese heritage.

Dang’s work contemplates the collision of the unknown and the familiar. It makes the observer question the experiences that shape our lives and structure our perspective of the world.

Both Lum and Dang visually embody the experiences that define our life stories. When someone tells our history, what images will they conjure? What do our stories say about us?

A Matter of Life and Death and Somewhere Else will be on display at the Art Gallery of Mississauga until April 16.