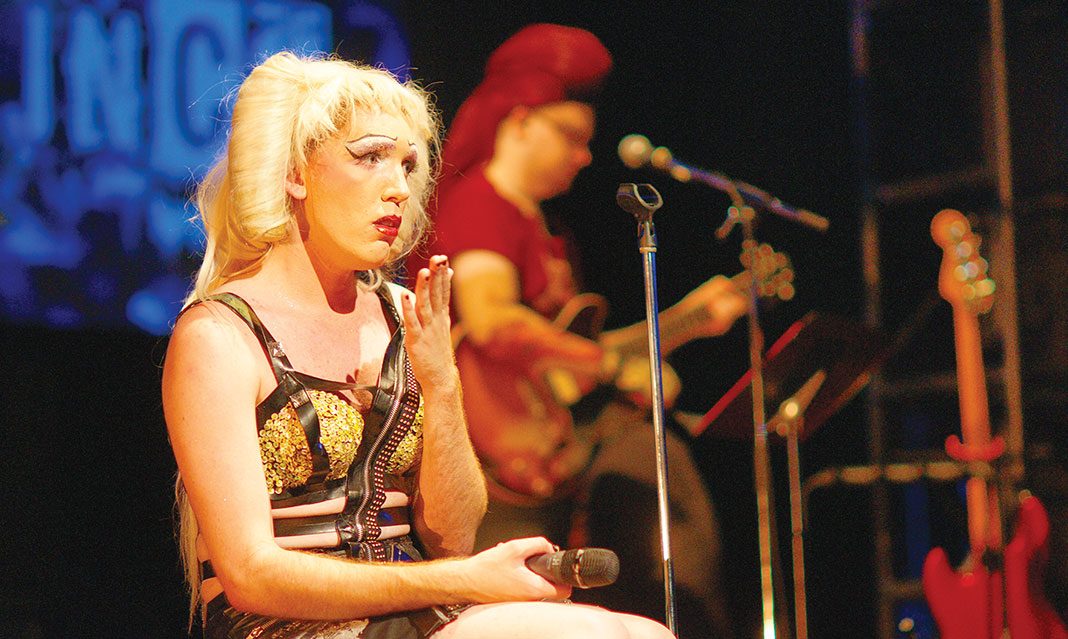

I like experiencing theatre without knowing the particulars of a production’s plot. So, when the title Hedwig and the Angry Inch arrested my vision, I prepared myself for the viewing of some sort of Harry Potter adaptation. However, when an androgynous actor—with no wand, scar, or round glasses—saunters onto the stage, my initial perceptions are shattered. Instead, Hedwig Robinson (James King), is provocatively dressed in knee-length high heels and tight clothing. As the show progresses, Hedwig sheds her long black cape, takes on different wigs, and becomes more scantily dressed.

Directed by Rebecca Ballarin, Hedwig and the Angry Inch is Hart House’s debut show of the season, and, I daresay, also its most risqué. Hedwig, musically accompanied by her husband, Yitzhak (Lauren Mayer), holds a cabaret-style performance, while her previous lover , Tommy Gnosis, performs at the Busch Stadium—an adjacent venue. Lovelorn, Hedwig remains bitter towards Tommy for the success he’s achieved performing the songs they’ve co-written together.

Hedwig, born Hansel Schmidt, was raised in East Berlin by an unsolicitous mother and absentee father. When Hedwig, still biologically a male, meets American soldier General Luther Robinson, she plans to marry Robinson and travel to the West. To complete marital requirements of being a man and a woman, Hedwig undergoes a bungled sex surgery leaving her with a “one-inch mound of flesh.” A year after her arrival in the United States, and subsequent divorce from Robinson, Hedwig hears that the Berlin Wall has fallen—her tribulations seemingly for naught.

Not long after, she meets, falls in love, and is rejected by Tommy Speck—whom she later gives the nickname Tommy Gnosis. Tommy cannot accept Hedwig when he learns she is not a cisgender woman. Thus, begins Hedwig’s long road to self-acceptance and forgiveness as she travels and follows Tommy’s tour after creating her own band, The Angry Inch. With bandmates Skzsp (Giustin MacLean), Krzyzhtof (Iain Leslie), Jacek (Erik Larson), and Schlatko (Robert Pucell), Hedwig rocks the stage.

Throughout the show, Hedwig and Yihtzak’s genderqueerness and sexual ambiguity were carefully portrayed by King and Mayer. King, speaking in a breathy voice while playing Hedwig, is physically contrasted to Yihtzak. Yihtzak, typically played by a female actress to further emphasize the play’s blurred gender lines, is petite in comparison to Hedwig.

Perhaps Genevieve Koski of The Dissolve explained it best when she describes the character of Hedwig to be neither just a man, woman, nor drag queen.

“Hedwig is a gay man without the physical maleness, who publicly identifies as female for want of better opinion,” Koski states.

A strength of the evening was the interactive nature of the performance. From time-to-time, King would step down from the stage speak to audience members. At one point, he climbs a chair and stands over a frazzled audience member while in stilettos. An impressive, yet nevertheless, startling feat.

However, I am not alone in this opinion: “What I loved in particular about the show was how interactive it was. My friend Arina, [a fourth-year CCIT student], and I sat in the back section of the theatre and we were both surprised when Hedwig was standing near us and talking to audience members,” says Cindy Do, a fourth-year philosophy specialist student. “I found myself laughing at some parts, singing along during ‘Wig in a Box,’ but also feeling sad while listening to Hedwig tell her story. It was easy for me to stay engaged with the show from start to finish because of its energy and the feeling of being in a live concert.”

Noteworthy is King’s persistently tireless performance. Hedwig’s dialogue reads like a never-ending stream of consciousness. After a song a monologue followed or brief dance, yet King never showed signs of fatigue or character dissociation during the almost two-hour duration of the show. Still, King persisted in his performance, changing his voice to suit a breathy Hedwig, deepening his voice when imitating Tommy, and taking on a Midwestern American accent for Robinson. All this proved that King was not only indefatigable but also versatile in his performance.

King also added some originality to his dialogue by adding in bawdy jokes, and disparaging Hart House’s architecture in a good-humored way. When Hedwig was describing how her intimate relations with Tommy caused her to lose weight, she smirked, saying, “I call it losing pounds by getting pounded.” Additionally, I appreciated the relevant Torontonian culture references, as well.

Mayer, too, delivered strong vocal accompaniment to the show. Her clear voice, which reminded me of Lea Salonga, ran in harmony with Hedwig’s rough and raspy vocals. Her voice was almost cathartic to listen to in that it was difficult not to feel my mood lighten up despite the emotionally heavy scenes.

In the script, Yihtzak is supposed to be bitter and resentful. Though at times I could see Mayer’s performance of Yihtzak corresponding with the script, generally, I saw sadness and pity of Hedwig in Yihtzak’s expressions. Consequently, even though Mayer didn’t seem to successfully emote Yihtzak’s resentment, I think her individual interpretation and emphasis of Yihtzak’s pain and pity brought out another aspect of Yihtzak. This adds a welcome complexity to the character.

As Ballarin states, the play explores themes about division, identity, love, loss, and pain. Ultimately, Ballarin notes Hedwig and the Angry Inch is about love and learning to be “unapologetically [oneself].”

Hedwig and the Angry Inch runs until October 7 at Hart House Theatre .