What defines loss? Is there one, singular way to mourn, or can this act be plural? These are questions Wilfred (Danny Ghantous) must confront when he learns the news of his father’s death.

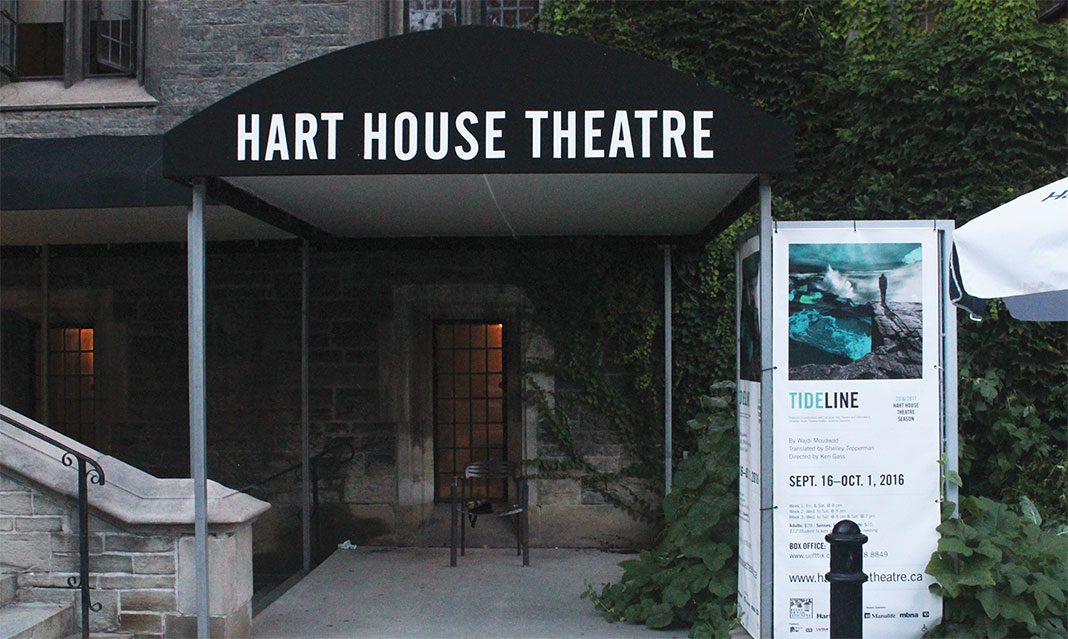

Tideline isn’t your average play about loss. In fact, Tideline isn’t your average play at all. One adjective won’t suffice, so I’ll use four: poetic, obscure, intense, and abstract. This is a play that brims with significance and urges you to confront the harsh concepts it puts forth. Wajdi Mouawad’s script is the perfect opener for Hart House’s 2016/2017 season.

Last Friday night, Tideline made its debut on the Hart House stage. Directed by Ken Gass, Mouawad’s script involves issues of family, loss, desire, war, and abandonment. The story primarily centres around Wilfred’s state of mind. When he receives the call that his estranged father (Erik Mrakovcic) has passed away, Wilfred is thrown into a turmoil of mixed emotion and self-doubt. Above anything else, Wilfred believes his father should be buried in his unnamed homeland, where he was forced to flee at the onset of war 25 years prior. Despite the objections of his eccentric family, Wilfred journeys to this foreign land to seek a burial spot for his father. But when he arrives, he’s met with a challenge—there are no vacant graves. The play then follows Wilfred as he treks across the country, carrying his father’s rotting corpse on his back, seeking a suitable place to lay him to rest. Along the way, he meets a cast of individuals equally as adrift and traumatized as himself.

The scenes flit between moments of supposed reality and Wilfred’s imagination. I use the term “reality” loosely, as the audience can never be certain where the story is taking place; elements of Wilfred’s imagination often overlap with the physical world. Yet, this play isn’t confusing. Oddly enough, it makes perfect sense the whole way through.

Accompanying Wilfred on his quest is his imaginary counterpart, the Knight (Angela Sun). The Knight is meant to represent a character from the stories Wilfred’s father used to tell him when he was a child. The Knight acts as Wilfred’s protector and guide. When Wilfred encounters a distressing situation, he summons the Knight, who heroically emerges wielding a sword, ready to lop off the head of the nearest antagonist. Problem solved, I suppose. These dramatic deaths are followed by the Knight’s sage advice, as she coaches Wilfred through his conflicting feelings. The lights then brighten, the beheaded characters rise from the floor, and Wilfred returns to reality.

These intermittent lapses in reality characterize Wilfred’s experience throughout the play. As I mentioned earlier, one can never be certain if Wilfred is dreaming or not. As he wanders through his father’s homeland, the corpse often stands and speaks to him, explaining hidden truths about his mother’s death and the country he fled from. We question whether or not we should believe the father’s stories, as his animation is seemingly a result of Wilfred’s imagination—are his facts true, or is Wilfred reassuring himself with his version of the truth?

Tideline blends somber, weighty subjects with an effortless dark humour. One minute you’re laughing as Mrakovcic pauses to smear green paint on his face—as he explains, he’s a rotting corpse and needs to look the part—and the next, you’re grimacing as one of the stragglers Wilfred encounters explains the graphic nature of his family’s death.

One thing this play lacks is restraint. The characters in Tideline are not ashamed to share the explicit circumstances that war brought into their lives. There’s Simone (Cassidy Sadler), whose family was ripped from their home and killed, Amé (Augusto Bitter), who murdered his father in cold blood, and Sabbé (Harrison Tanner), who couldn’t help but laugh as his father was beheaded. Despite my cringes during some of these stories, war is a heavily influential topic that shouldn’t be toned down to spare the audience. These characters need to tell their stories in the same way that war-torn individuals in the present need to share theirs. Wilfred’s father symbolizes the fathers of each character as they cope with the horrors that plague them and their country.

Contrasting the tumultuous circumstances that unfold on stage is the use of minimalistic props, costumes, and set pieces. The stage was void of any colour; everything was painted white. The actors used few props, and their clothing was plain. For instance, Sun wore basic black pants and a shirt, with only the large sword tucked into her belt to indicate her character.

This simplicity certainly functioned to the cast’s advantage. The stage was comprised of moving platforms that were used in every scene. The actors used these versatile pieces to elevate themselves during monologues or to display different scenes happening in the background. One platform jutted out to the side of the stage, allowing Ghantous to charge into the audience in the opening scene and make his appeal to a judge.

As the cast of Tideline manoeuvered through this setting, I couldn’t help but admire the choreography. The movements of the actors were intricately designed and well-rehearsed throughout the scenes. This performative element added to the depth of the script, as it created implications that would otherwise go unsaid through dialogue alone. In one scene, Wilfred and his family are gathered at Wilfred’s apartment. They sit in a diagonal row of chairs, talking to each other while staring straight ahead. They direct their speech beyond the audience, but respond to each other as if they were speaking face-to-face. Only when the conversation escalates do the characters turn and face one another. This scene was beautifully synchronized and expanded on Wilfred’s family dynamic, including the detachment, hostility, and secrets that circulate their relationships.

Tideline is dense with emotion, meaning, and hidden contexts. I could talk for hours about the convoluted plot that unfolded before me, but I’m afraid that my words alone wouldn’t do it justice. Mouawad has created a script wrought with raw human experience and Gass has brought this vision to life through his direction.

Tideline runs until October 1 at Hart House Theatre.