Has the moment of decolonialism passed? Or is it still going on, bringing up questions of former colonists’ responsibility to reconcile some of the violence?

The Blackwood Gallery’s film screening series “We Must Invent”: Film and the Unfinished Project of Decolonization explores how African filmmakers reflect on those questions.

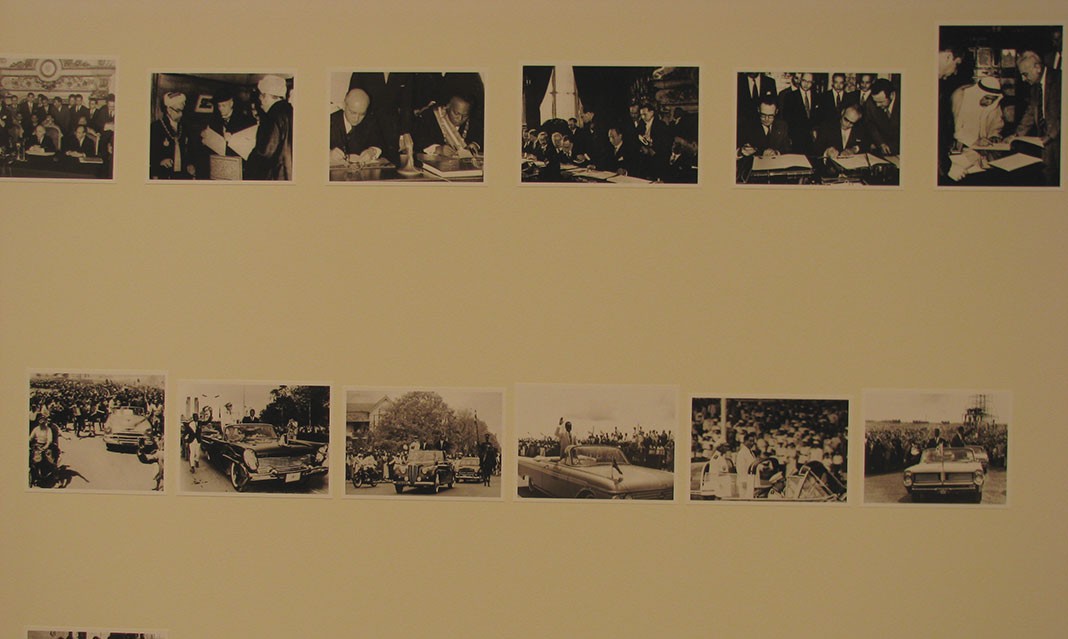

The series is in context with Maryam Jafari’s The Day After, an exhibit that looks at 30 years of the postcolonial movement through photos. The Blackwood Gallery teamed up with UTM African history professor Julia MacArthur to curate the series.

“The question of decolonization is a question that I think resonates in Canadian history as well,” MacArthur says. “The settler’s politics and indigenous histories that we have in our country are similar to these issues being grappled with on the African continent.”

The Blackwood Gallery screened Swedish director Göran Olsso’s 2014 documentary Concerning Violence to begin the series last Wednesday in the e|gallery. The filmmaker put together archival footage from the ’60s and ’70s with Franz Fanon’s 1960s text The Wretched of the Earth.

Fanon worked as psychiatrist in an Algerian hospital in the 1950s during the war of independence. His experience influenced his text; The Wretched of the Earth contains a chapter called “Consequence of Violence”, which inspired the documentary. Singer and activist Lauryn Hill narrates that chapter in the film.

Olsso includes footage of interviews with the guerrilla soldiers of FRELIMO in Mozambique, the everyday experiences of those fighting for independence, and the views of white settlers in South Africa and Rhodesia.

Much of the footage features close-ups of speakers’ faces. In an interview with one of the guerilla fighters, the man smiles when he talks about how the medical training he’s learned will contribute to guerillas’ fight for freedom. When he stops speaking, the camera rests on his face as he looks down and the smile disappears, almost as if he’s turned inward to his doubts not voiced in the interview.

As a documentary, Concerning Violence includes direct images that disturb in their honest portrayal of the effects of violence. For instance, Olsso chose to include a sequence that focuses on a mother and child injured in a bombing. The camera focuses on the mother’s sad yet expressionless face. The camera then pulls away to show the raw stump below her shoulder. A baby waving its arms fills the screen. The camera pulls away to show the baby has lost its leg above the knee. The last image of the mother nursing her child after their wounds have been bandaged conveys a sense of loss and powerlessness to the viewer.

Olsso’s choice to include footage that offers close-ups of people’s faces, dancing scenes, sharing a bottle of water, and guerilla soldiers marching through the forest juxtaposes the humanity of those fighting for their freedom with the violence they encounter.

Towards the end of the documentary, Olsso includes an interview with Thomas Sankara, a Burnikabé military captain. The off-screen interviewer asks why Sankara has refused food support. Sankara responds that food donations of corn or milk from other countries are not true food support. True food support would be donations of shovels, plows, irrigations systems, and farming tools to rebuild the decolonized nations.

Olsso makes the archival footage of Sankara’s interview relevant to today’s audiences with the way he coordinates Franz’s text to explore the lingering violences and injustices of the postcolonial world.

The next film screenings will be on Wednesday and February 24.