People have always had a fascination with the lives of the rich—it’s what keeps reality T.V. shows popular. When you see the paintings of artist and feminist Florine Stettheimer, you have a feeling that the artist may have had a hitch about this sensationalism. Since October 2017 until this January, the Art Gallery of Ontario is giving patrons a look into the life of Stettheimer in the exhibit called Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry. The exhibit explores the modernist brush strokes of the American poet and painter.

Hosted in a quiet section of the AGO, the exhibit welcomes you into a large room with colorful paintings hung on a white wall and a second section housed in the middle. Stettheimer is famous for her vibrancy and her work doesn’t disappoint. Her love of flowers and bright colors give her paintings an approachable charm. Separated by acts, the exhibit moves you through stages of the artist’s work, as you’re passed through portraits of people close to her.

A huge dark portrait of Steittheimer’s older sister—“Carrie”—opens “Act One: In The Family.” The painting looms over the rest of the exhibit as Carrie’s gaze seems to watch you. Is this how Steittheimer felt about her older sister? Paintings of the family’s house come next. In it, small figures of her sisters in the garden stand on the right, and a painter bends over an easel on the left.

“Act One” moves you through individual women of the family until you reach, “Portrait of a Woman with Red Hair.” The painting is thought to be Stettheimer’s first self-portrait. It shows the modern woman—in contrast, to the paintings of her aunts and sisters in gowns and long hair—in an androgynous way, with cropped red hair and a dark suit.

Another painting, “The Fourth of July,” preps the viewer for the light paintings that come next. The painting itself is one of the only pieces in the exhibit that doesn’t include people. Rather, it shows the American flag with fireworks set off in the back, symbols of America being a theme in the artist’s works. A series of family portraits end “Act One.” The women of the family are shown at their various homes or in their gardens laying leisurely with bright fruits and flowers around them.

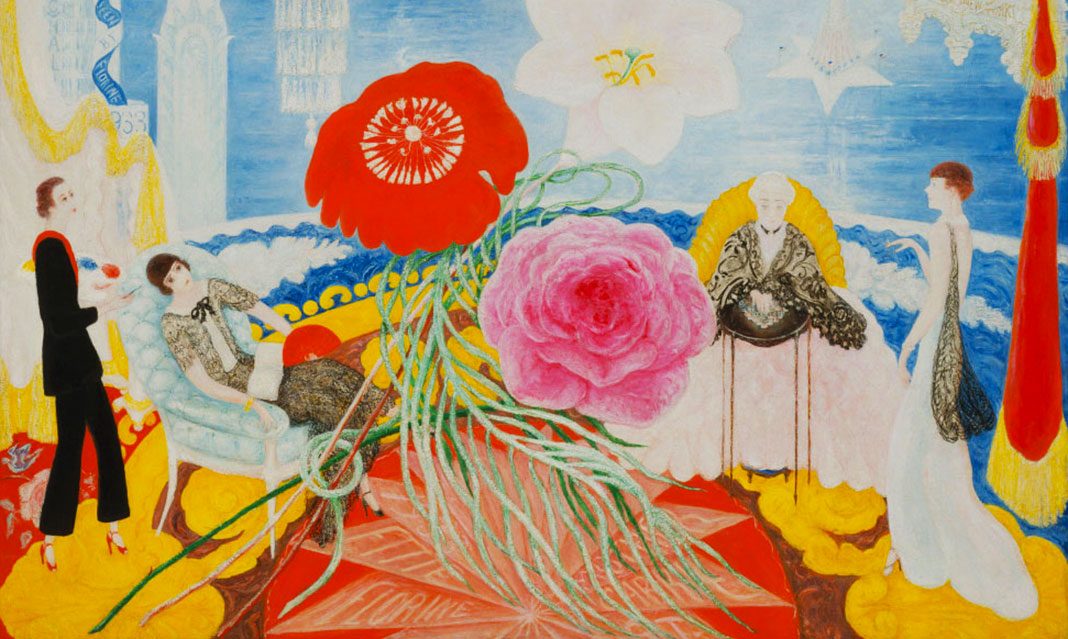

“Act Two: By Invitation Only” introduces you to Stettheimer’s friends: artists, intellectuals, and writers stand alone for their portraits surrounded by colorful scenes. These were the people Stettheimer surround herself with—prominent modernist and feminist thinkers of the Jazz Age that helped push the envelope on the way people thought about class, race, and religion. The portraits prime the observer for the final act, showing you individual guests that would have attended Steittheimer salons, so beautifully depicted in “Act Three.”

“Act Three: Acting Out” immortalizes scenes that would have been taken place behind the closed doors of the artists salons. The paintings depict the lavish soireé’s that hosted people who redefined femaleness and sexuality. Stettheimer showcases the elaborate furs, feathers, and cocktails of the rich of the era she navigated, giving the observer a peak into the dwellings of the Jazz Age most influential.

Only by witnessing all three—Florine as painter, poet, and set designer—can you appreciate the artist.