This article has been updated.

| March 30, 2017 @ 4 p.m. | Quotes and other material were added. |

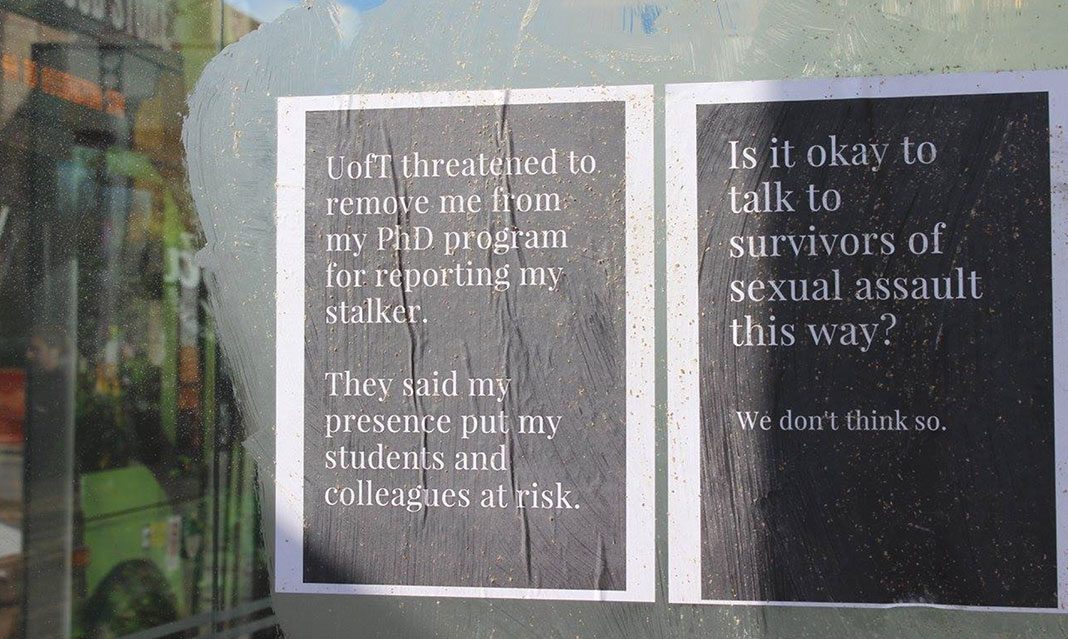

Silence is Violence – University of Toronto released their “Survivors Speak Back” campaign on March 16 in an effort to share stories from sexual assault survivors and their experiences with U of T administration. Shortly after, the university removed their posters across campus amid concerns of policy breach.

Among the many posters were, “U of T paid my rapist to live at a hotel across from my residence throughout the investigation”; “When I asked the university why they’d rehired my rapist to work with undergraduate students after finding him responsible, they said: As far as we’re concerned, the case is closed”; “My rapist was fired from his Student Life position following the attack. He was rehired to a different division of Student Life shortly after.”

A tweet by Silence is Violence on March 19 alleged the university of removing the posters. “Using boxcutters and screwdrivers, U of T paid to scrape the words of survivors of #sexualviolence from the campus,” it stated.

The founder of U of T’s Silence is Violence, Ellie Adekur, told The Medium in an interview that the university hired the contractors the following morning after the posters were hung. She stated that they specifically removed the sexual violence-related posters.

“The university hired contractors to come to the St. George campus specifically to remove the Silence is Violence posters,” she said, “And we only really know that because I ran into a crew of them when I was coming into my office the next morning, and I just asked them who they were and why they were only taking down the posters about sexual assault and leaving out all the other ones.”

U of T’s executive director of personal safety, high risk and sexual violence prevention and support, Terry Mcquaid, in an interview with The Medium, did not confirm or deny, when directly asked about the claim of hiring of contractors. She responded that the posters were removed because the university has a policy on areas where posters are approved, and people can only post in those approved areas.

When asked if the Silence is Violence group posted it in a non-approved area, Mcquaid responded saying, “I’m not completely aware of that, but from my understanding, at the approved areas, all the posters are there.”

Adekur did not confirm Mcquaid’s comments. She stated to The Medium that the posters were removed from every location on campus, including the public message boards.

“We’re also currently dealing with staff removing posters from indoor message boards on campus too,” added Adekur, “I think Terri is saying what she needs to in her role, and it’s disappointing, but largely something to be expected from the University.”

U of T’s director of media relations, Althea Blackburn-Evans reached out to The Medium on Monday to deny that the university hired contractors and that the posters were rather removed because of postering policies, not because of their content.

“The university did not hire contractors. The university does not hire contractors to remove posters,” said Blackburn-Evans. “They’re removed either by care-taking staff if they’re inside buildings and in places where they shouldn’t be, or they are removed by ground staff if they are outside. I want to clarify there, outside means still on the university’s property. If they’re outside on city property […], the university does not touch city property.”

“We have guidelines for postering. We certainly welcome and allow students to do postering in particular locations, so there are messaging boards, and things like that, like bulletin boards where postering is allowed. If postering happens in other places, where it’s not allowed, where it’s not set-up for posters, […], posters will be taken down,” said Blackburn-Evans. She added that “it has nothing to do with content. It’s only about where things can and can’t be placed. The university doesn’t make judgement calls about the content of posters.”

When asked why Mcquaid did not deny the allegation of hiring contractors, Blackburn explained that postering “is not really Terry’s area.”

“So it’s not really Terry’s responsibility to confirm how postering gets handled because it’s not what she’s focused on,” said Blackburn-Evans. “She’s focused on supporting those who experience sexual violence.”

The Medium had reached out to Laura Bradbury, the director of the Office of Safety and High Risk, who stated on March 22 that she was not in office and directed The Medium to Mcquaid. Blackburn-Evans had also directed The Medium to Mcquaid on March 21, after requesting the questions that will be asked in advance to see who the campus newspaper can speak to.

When asked in the interview with Mcquaid on March 23 why The Medium was directed to her instead of talking to Bradbury and Blackburn-Evans, Mcquaid explained that she is the one who oversees the activity of the Sexual Violence of Prevention and Support Centre in terms of supporting the conversations, and is the point of contact, since she has a role in the education prevention that is in partnership with different actors across the university.

The Medium also interviewed two of the participants and the organizers of the Survivors Speak Back campaign: Paylysha De Gannes and Tamsyn Riddle.

In response to the university’s removal of the posters, De Gannes stated that she’s not surprised at the move. “I also do understand the administration’s standpoint on why they did that, because it’s all about upholding reputation, so I’m not necessarily surprised,” she said.

Riddle stated that she, along with other organizers, were first “discouraged” by the university’s move to take down the posters. However, she added that the campaign’s Facebook posts attracted over a thousand people interacting with them, as well as sharing and talking about the stories.

“The whole dialogue is to literally take these stories and put them all over the campus, [so that] survivors would be able to see these and understand that ‘We’re not the only ones,’” said Riddle. “And [while people are] walking around campus, they would sort of have to confront it and be able to learn about it. And it also serves as a way to be able to tell the administration what is going on.”

Among the other posters were allegations against the university for not acting enough upon the survivor’s report. Another poster addressed the Community Safety Office, alleging it wouldn’t allow one of the survivors to stay in emergency housing “after they contacted my stalker without telling me.”

“I can’t speak to specific cases; I certainly can speak to the desire of the university with the policy to move forward in responses and sensitive ways to meet the needs of the survivors, and […] reaching out where we know that people want to see supports, accommodation, and services,” stated Mcquaid, in response to a question on how the university deals with these alleged sexual violence cases.

De Gannes also addressed that the new sexual violence policy did not implement the consultations that were held in advance with the U of T community. According to her, the consultations offered a good space for different people to provide their views. However, she said that they had their drawbacks.

“[…] During the entire counselling session, counsellors were on their cell phones during the entire consultation,” said De Gannes. “So if I felt that something was uncomfortable for me, I don’t know how I would feel using their support when they are being paid to be there and they couldn’t even spend two hours paying attention. They were literally on their phones the entire time.

“The consultation process was okay in itself, but upon the publication of the actual policy, it was interesting how little of what was mentioned in our consultation actually made it to the final draft,” De Gannes added. “[Although there are] terms that are well-defined or adequately defined, there were other documents the university used as a reference, so in order for you to get a full comprehension of the policy, you have to refer to those other documents.”

De Gannes added that these documents did not go through the recent consultation process.

Mcquaid addressed these claims, stating that she has heard of what consultants feel not being included in the final draft of the policy. She stated that there are lots of opportunities, however, to include their opinions in other levels related to the operations of the Sexual Violence Prevention Centre.

“There’s lots of opportunities to include those thoughts in the centre operations; things like including students in the education, and provincial rollout and things like that. That’s where that information belongs,” said Mcquaid. “So we’re going to be building those partnerships with various groups who want to be involved. I think we’re so much in the right direction to have those requests mapped.”

The Survivors Speak Back campaign was ignited with a question, which Silence is Violence posted on Facebook, asking people if they have experienced sexual assault.

“We basically just said: If you’ve experienced sexual assault at the University of Toronto—or not even that, if you’ve experienced sexual assault period […] in any capacity, either you chose to report or if you’re looking for academic accommodation or mental wellness, tell us what happened,” said Adekur to The Medium, in regards to how the campaign started. Within the first 24 hours following this question, the organization received around 70 responses.

Mcquaid told The Medium that she hopes the organizers of the campaign coordinate with her to work on what the survivors want and to create spaces for them to “come forward and to disclose.”

“It’s a large institution […], so collaborative relations are going to be really helpful to get this message out and make sure that on the ground, people are supported; and even for those responders who are dealing with the impact, they are given the education […] needed to get the message out, so I’m really looking forward to what work we can do together moving forward,” stated Mcquaid.

According to Adekur, the next branch of the campaign will focus on who’s responsible for what is happening at U of T, as well as what they can do to confront the university and ask for a change