Once upon a time, old media reigned and many editors were influenced by government and advertising politics. Then came the Internet with its blogs, citizen journalism, and ease of access. The new media gave people the ability, to an extent, to say whatever they wanted, and also to find out, to an extent, whatever they wanted.

Once upon a time, old media reigned and many editors were influenced by government and advertising politics. Then came the Internet with its blogs, citizen journalism, and ease of access. The new media gave people the ability, to an extent, to say whatever they wanted, and also to find out, to an extent, whatever they wanted.

And then came personalization, where the Internet already knows what you want to find out. Sounds good, right?

Now, if you’re a CCIT student, you’re probably just about ready to turn the page because you’ve heard this all before, but bear with me. To you non-CCITers, the Internet knows what you want to see by tracking things that you’ve already seen. Ever wonder why some people just never show up on your Facebook Newsfeed?

That’s because Facebook uses a complex algorithm called EdgeRank. EdgeRank uses friendliness, content weight, time spent, and other things to decide what ends up on your Newsfeed and in what order. Google also collects information about your likes and dislikes. Through Gmail and a few other things that fall under the category of Google Accounts, Google decides what order you search results will end up in. Other things also influence Google search results, like what city you’re in and how old Google thinks you are.

We’ve seen this kind of thing at work in iTunes’ Genius system, Netflix, and others. But while there may not be too much harm done to society if you continue to listen to Katy Perry and never discover Mother Mother, what happens when you and I get different Google search results for the same key words?

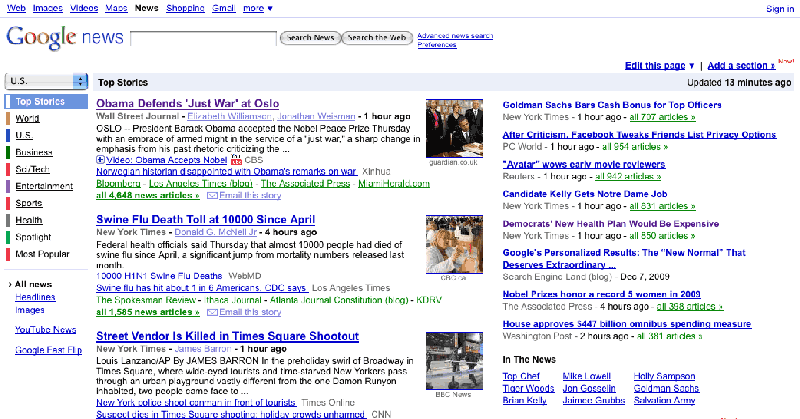

Even personalization on Facebook doesn’t seem so bad until you find out that most people today get their news from their Facebook Newsfeed instead of actual news sites. The same goes for Google News.

Eli Pariser, author of The Filter Bubble, suggests that the path toward more and more personalization will result in an undemocratic web, perhaps even a return to the era of old media gatekeepers. Why? Well, because in the ideal personalized web space, you would only be getting information that you want to see. But sometimes it’s important that we get exposed to things that shock, surprise, or disgust us—otherwise how would we know what was really happening in the world? If your “filter bubble” is only full of Lady Gaga hits and TMZ news, how would you ever find out about the famine in Somalia or the euro crisis summit next Wednesday?

That’s not to say that everybody only listens to Lady Gaga and reads TMZ all the time, but the idea is there. People need to be exposed to things they don’t want to see in order to learn new things. How can you make sound decisions if you’re not getting the full picture?

Pariser says filter bubbles are dangerous for this reason, but also because most people have no idea they’re in them. Most people don’t know that Google deduces their age and personality based on what browser they use. And although Google probably thinks I’m a middle-aged man, it’s still ordering and displaying search results for me based on that information, without my knowledge.

The new “subscribe” button on Facebook actually seems to be a step in the right direction. At least now you have some choice in who ends up on your Newsfeed. Still, in a TED speech, Pariser directly addresses Google, Facebook, and other Internet administrators asking them for more democratic curators of our online information. What happens next in personalization remains to be seen. The best thing to do right now is try to burst your bubble every once in a while.