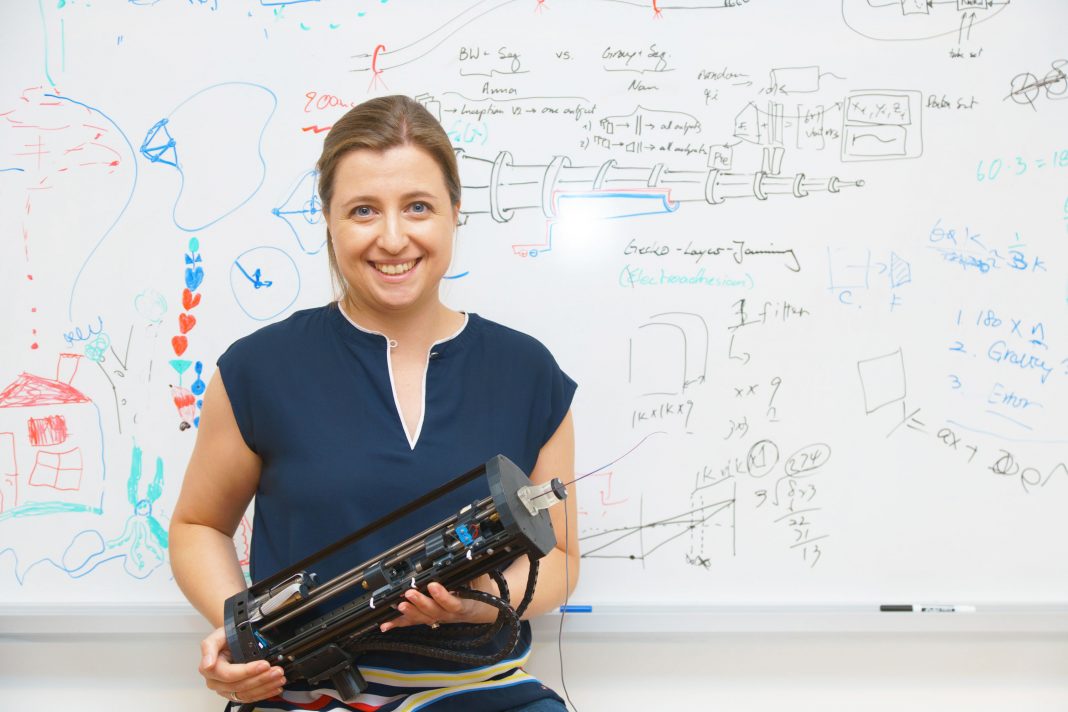

Passionate about her work and highly accomplished, Dr. Jessica Burgner-Kahrs, Associate Professor and Director of the Continuum Robotics Laboratory, joined UTM this spring. The Medium sat down with her to discuss the unique field of continuum robotics, her academic journey, and her lab’s research.

Burgner-Kahrs explains how “continuum robotics is very different from what [one] commonly know[s] as a robot. Continuum robots are inspired by nature, for example, like elephant trunks, tongues, and worms. [They] don’t have any rigid links or joints [and] are actually continuous in shape.”

Their design allows them to “sneak around and have individual curvilinear shapes,” which, coupled with the fact that it is possible to build tiny versions, “makes continuum robots favorable for all sorts of applications [where] reaching out into areas” is required. An important example would be medicine where continuum robotics can be utilized to reach within the human body for surgical purposes.

During the interview, Burgner-Kahrs shows me a few of the robots her lab is working on. She explains how “continuum robots are very compliant so they are very safe to use close to the human or even within the human [as] they cannot do a lot of harm.” While the robots “cannot lift heavy objects like a regular robot, they can exert small forces.” This ability is helpful in “grasp[ing] tissue to bring a laser source or deliver a drug to a certain location [and] even do some small resections.”

Burgner-Kahrs tells me that “these robots could be very useful in minimally invasive surgery” and that neurosurgeons are already excited about a tiny, tentacle-like robot which can be used to precisely deliver laser treatments to tumours without having to open up the skull.

The continuum robots can also benefit industrial applications. Burgner-Kahrs says that for the “maintenance and repair [of] object[s] such as aircraft engines, the robots could sneak in and observe if all the turbines are still intact. These robots could help automate this process to make it less tedious for technicians.”

When asked about what inspired her to pursue this field, Burgner-Kahrs credits “different things [such as how] robotics is a mixture [of] computer science, mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, and mechatronics.” Viewing how “all these fields come together was always [tremendously] exciting for [her].”

Furthermore, even though she “loved robots when [she] was a kid,” Burgner-Kahrs “always thought [she] would go into medicine.” However, one incident in her life prompted her to consider other pathways. As Burgner-Kahrs recounts, one of her uncles passed away as a result of a brain tumour. Before his death, he received irradiation therapy. “In this therapy, the machine has to be oriented and positioned so that the radiation goes to the tumour.” However, when applied to Burgner-Kahr’s uncle, the machine “was slightly off and so [the machine] radiated [part of the brain] but not the tumour, [and therefore] the tumour kept growing.”

The incident prompted Burgner-Kahrs to ponder about how she “could help surgeons and physicians to do their job better.” Already passionate about computer science and technology, Burgner-Kahrs was confident that computer science could be utilized to “help surgeons [administer] more reliable treatment.”

During her undergraduate degree at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) in Germany, Burgner-Kahrs took “all the courses possible on robotics.” Burgner-Kahrs was also a student researcher in a “big research project on robotic-assisted surgery” at KIT and thought that she would continue working with conventional robots. However, during her Ph.D. at KIT, she attended a talk on continuum robotics given by Dr. Robert J. Webster III who would then become her post-doctoral supervisor. She was instantly mesmerized and knew that she needed to work on what she strongly believed would “be the next generation of robotics.”

Burgner-Kahrs then successfully applied to work for Webster and moved to Nashville, Tennessee to work with him at Vanderbilt University, following which her journey as a professor and researcher commenced. She worked at Leibniz University Hannover in Germany for six years before her appointment at U of T where she “loves working with students” and building robots in her continuum robotics lab.

In her lab, Burgner-Kahrs and her team conduct research on and build continuum robots. She describes how they “do fundamental research by thinking about new robot designs, the mathematical modelling of the robot, human-robot interaction, and application-driven research where [they] interact a lot with surgeons to determine potential applications.” Her lab is composed of students from various disciplines including computer science, electrical engineering, and mechanical engineering.

Her advice to students who are interested in continuum robotics is to firstly “take the Introduction to Robotics course.” Moreover, she says that she is “always taking on students as volunteers [and] personally convinced that everyone can contribute no matter what their experience level is.” Though she acknowledges that “continuum robotics itself is a little bit more advanced [type of] robotics,” she is a very strong mentor and appreciates everyone’s contributions.

Burgner-Kahrs assures students that “[she] will make sure that [those who work with her] will have a good experience and will learn something.” On top of regularly meeting with students, she “always assign[s] a graduate student as a mentor [to undergraduate students] as well.” She highly encourages getting involved in research and believes that if “[one is] motivated and really into the topic, that’s when [they] will perform the best.”

Her hobbies include cooking, travelling, and walking outdoors. However, Burgner-Kahr’s main interest and favorite past-time is her work. She states that she “really love[s] what [she’s] doing and [doesn’t] see it as work” at all.