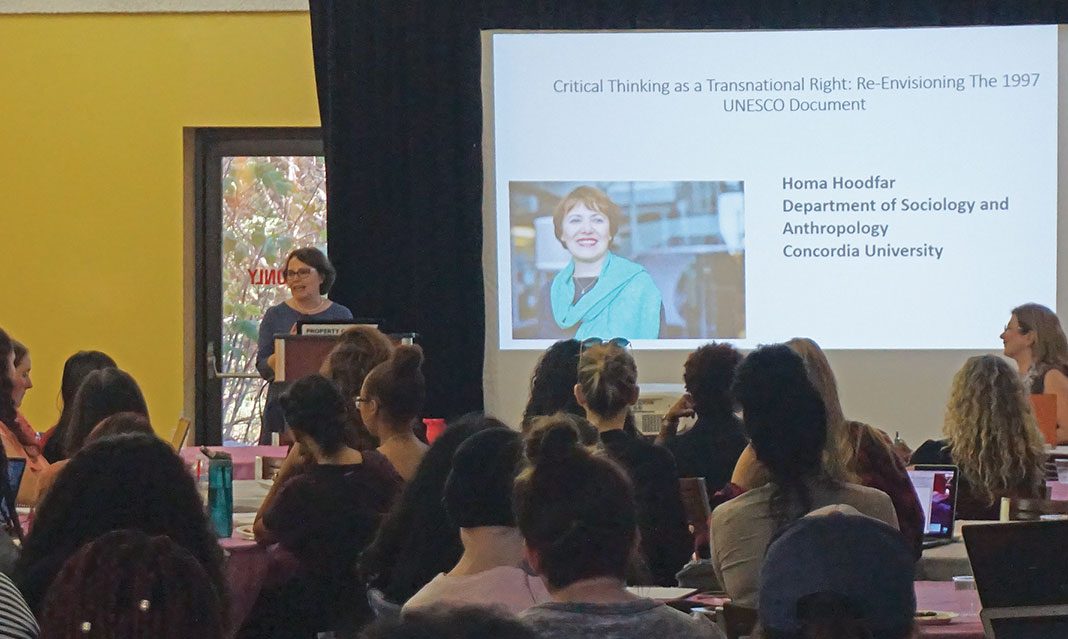

Professor Homa Hoodfar of the Department of Anthropology and Sociology at Concordia University spent 112 days in prison in Tehran, Iran. The Iranian-Canadian anthropology professor was arrested while on a personal and research visit to Iran, according to her conversation with CBC News published on the day of her release, September 26, 2016. One year later, on September 26, 2017, marking the one-year anniversary of her release from prison, the women and gender studies department of UTM hosted Hoodfar for a talk titled “Critical Thinking as a Transnational Right.” Professor Hoodfar discussed the role of academic freedom in a global context and also in her personal experience.

Citing her previous academic work, Hoodfar stated that her interrogators, the Iranian authorities, claimed that she had come to Iran on a political mission to agitate women and bring about a feminist revolution, changing the nature of the state in Iran. When Hoodfar attempted to show that her reasons for being in Iran were academic and had no political purpose, she was confronted with the idea that everything she says is considered political because she is a professor, a person of authority who people will listen to. Her interrogators added that academic freedom is a western concept and is not needed in Iran.

“Academic freedom is a privilege,” Hoodfar explains, “It is a collective right and a responsibility and [although] academic freedom is frequently discussed as a right, often people forget about the responsibility attached to these rights.” Hoodfar also describes how, no right comes without responsibility. “Academic freedom means one must act as a public intellectual. It is a public intellectual’s responsibility to talk to the public and present their ideas. Academic freedom requires the support of the public to be maintained.”

Hoodfar, however, mentions that academic freedom does not mean that academics can do and say whatever they want, whenever they want. “It is the freedom to speak. within their expertise, using the foundation of critical thinking to advance the common good by creating knowledge,” she says. Critical thinking is innovation and creativity, Hoodfar describes, and it refers to the ability to think beyond merely identifying the problem. “We have to mind ourselves, and our students, that critical thinking isn’t just questioning everything, but using your imagination to develop solutions.”

Academic freedom is important, even in countries like Canada, where matters of personal freedom are protected by law. According to Hoodfar, academic freedom goes one step beyond freedom of expression. It allows people to say things that are not necessarily common or publicly accepted without having to be afraid of losing their job or going to jail for expressing their views.

Yet even in Canada, arguably one of the most democratic countries in the world, there is research being conducted, but the results may not be published, Hoodfar explains. One possible barrier towards publishing could be, as Hoodfar describes, the wording of grants used to fund the research. When conducting research in other countries, Hoodfar says, “Academic freedom can be non- existent, and yet there has never been a major discussion about academic freedom in practice, although there have been attempts to ensure the sanctity of academic freedom internationally.”

According to the anthropology professor, UNESCO was supposed to be the blueprint for international academic freedom, but she believes that “60% of the countries who have signed the document don’t know what is included.” If international relations have been unable to achieve their goals, it is time for a change in focus from international to transnational rights. The Iranian-Canadian professor adds that while “international” typically refers to agreements and discussions between government, “transnational” refers to public-to-public actions. Transnational, as Hoodfar describes, may include the government, but it is not mandatory for those actions. Hoodfar also says that public-to-public actions can be just as effective as governmental actions: “Legitimacy does not come from the state. Legitimacy comes from the public knowing that you are committed to improving their way of life.”